So how did London’s two big opera companies launch their new seasons last week? Not perhaps in the way you might expect. Decked with pink balloons and the acrid smell of popcorn, the Royal Opera House waved the garish contemporary flag with Mark-Anthony Turnage and Richard Thomas’s Anna Nicole of 2011, revived before a youthful opening-night crowd attracted by specially subsidised tickets. It was left to the friskier English National Opera to offer a new production of sober mien and an audience containing some people who dressed up. Standard repertoire, too: the opera was Verdi’s Otello — filled enough with base passions, but not with phrases like ‘douchebag’ or the delightful ‘skid-marked panties’.

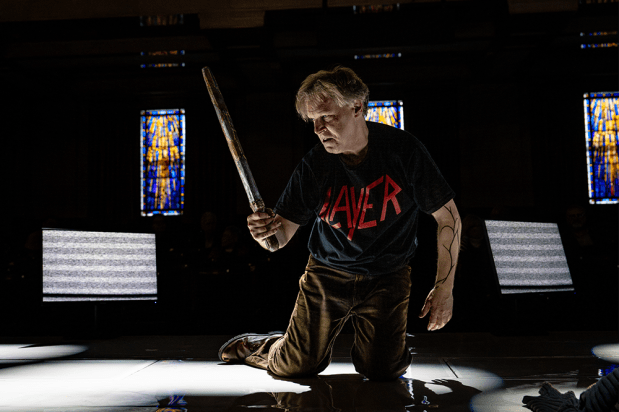

The Coliseum threw the best party, by far. David Alden’s latest ENO venture in a relationship now going back 30 years contains enough of his trademark quirks, but remains at heart rock-solid. Jon Morrell’s towering set and Adam Silverman’s dramatic lighting sat us down in the distressed interior of a fortress church, with characters’ menacing shadows occasionally thrown on to its gaunt grey walls. The time period? Early 20th century. Furniture? Little more than two tables, plus an armchair for Otello to hurl: he likes being very physical. Indeed it’s in his muscles and tempestuousness that the otherness of Alden’s Moor lies — certainly not in the pallor of Stuart Skelton’s skin.

A ‘whitewashed’ production, then. Nor is this one that makes much play of religion, despite the Act Three moment when Iago and Cassio start using a Madonna icon as a dartboard. Yet this light skating over race and religion still doesn’t drain power from the show, nor from Skelton’s performance. Brooding stage charisma, vocal punch, dramatic fireworks: the star of Alden’s ENO Peter Grimes gives us his all. Possibly too much so at times: when he flares up and flings his furniture, Otello the warrior hero risks seeming just a troublesome teenager throwing a tantrum. We need to glimpse more of his internal life.

There is plenty of firepower elsewhere. Jonathan Summers makes a marvellously duplicitous Iago, garlanded with malevolent eyebrows, dressed like a communist agitator hotfoot from Brecht. His voice is convincingly harsh and world-weary; and he spreads black bile even when distantly sitting in Alden’s disorientating climax, calmly observing Otello’s final agony as if waiting for a bus. In her UK debut, the American soprano Leah Crocetto creates a Desdemona with attractive spunk and a clarion, fast-vibrating voice perfect for sudden irruptions, though less so for love’s sweet nothings. Her own end is disorientating, too: no pillow smothering, no bed to lie in, just a brutal choking against the back wall and a crumple on to the floor.

Through all the other top-notch attractions — Allan Clayton’s eloquent Cassio, the vigorous chorus, Peter Van Hulle’s foppish Roderigo, Pamela Helen Stephen’s proto-feminist Emilia — Verdi’s amazing orchestral finery keeps on glinting. Right from the first thunder blasts, Edward Gardner and his musicians give every instrumental nicety and visceral shock their due. Gardner’s last ENO season as music director has begun with a terrific bang.

And how did Covent Garden’s new season get under way? Not with a whimper, certainly: that wouldn’t be possible with a hot and heavy Turnage score conducted by Antonio Pappano, or a topic like Anna Nicole Smith, the American model and reality TV star who died in 2007 of naivety, prescription drugs, and too many silicone breast implants. Yet a second look at Anna Nicole reinforces the view that this opera never quite comes to the boil, even in a vigorous revival blessed with most of the original cast.

There is satire, but not enough of it. There is lyricism, but not enough of it — or at least not spiced with sufficient personality to generate all the pathos needed to make Anna’s absurd life worth our time. We also need more audible singing. Amplified performers usually make me foam at the mouth, but on press night I yearned for a discreet helping hand for singers fighting the Royal Opera brass. As before, Eva-Maria Westbroek throws heart, soul and other things into Anna’s whirlpool, though surtitles still had to be consulted before every penny dropped.

At least no shrinking impact affects the concrete elements of Richard Jones’s production, revived by his close namesake Richard Gerard Jones. Miriam Buether and Nicky Gillibrand’s luridly coloured sets and costumes still dazzle and tease in a Jeff Koons kind of way. Westbroek aside, we get potent performances from Susan Bickley (the mother), Alan Oke (her billionaire oil strike), and Rod Gilfry (lawyer, Svengali). But I’ll still stick with ENO’s Otello, where music and characters walk hand in hand, and the drama cuts us to the bone.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in