1984 and all that. Which side were you on? The side of Margaret Thatcher, her hairdo and person standing rigid against a rising tide of industrial activism and British declinism? Or the side of the miners, socking it to the Tory scum and their jackbooted adjutant, Johnny Law?

There’s no doubting which side this new movie Pride is on. It’s about a curious episode in community relations when a group of gay people from London decided to fundraise and rabble-rouse on behalf of the striking miners in Wales. It starts with a shot of a red banner — ‘Thatcher Out!’ — hanging from a council-block window. And it ends with a discussion of which phrase will work best on a placard: ‘Screw you, Thatcher!’ or ‘Fuck you, Thatcher!’ They go with the former. ‘More visceral’, apparently.

But don’t let the politics scare you off. There’s actually surprisingly little of it. Once it gets going, Pride is mostly a light comedy about folk in unexpected settings — like those films in which a knight ends up in modern-day New York, or when Gordon Brown attends Parliament. The gays look exquisite in their eyeshadow and jewellery. The miners look careworn in their mossy jumpers and raincoats. The two groups meet, clash and eventually learn to love one another because we’re all humans, aren’t we? You know the drill.

The best parts of Pride are those that investigate these tensions. For instance, there’s a scene in which our heroes from LGSM — Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners, natch — play bingo alongside the Welsh villagers. It’s funny on that simple, ha-ha level of seeing neon Londoners in a pebble-dashed community hall. But it’s also funny because one of them takes the opportunity to declare a breakaway group called ‘Lesbians Support the Miners’. It’s a joke as old as Life of Brian, but it makes a serious point: how many causes have been foiled by petty vanity?

Sadly, Pride has petty vanities of its own. Despite heading in some intriguing directions, it often rushes back along an unchallenging path. And so we have the miners staring down into their pint glasses, wary of the queers in their midst. Yet all it takes to shake them from their fear and prejudice, and have them cheering into the ceiling, is a mid-film dance routine by Dominic West. It is, admittedly, a raucous and rollicking dance routine by Dominic West, but it’s still just a dance routine. As resolutions go, it feels pretty cheap.

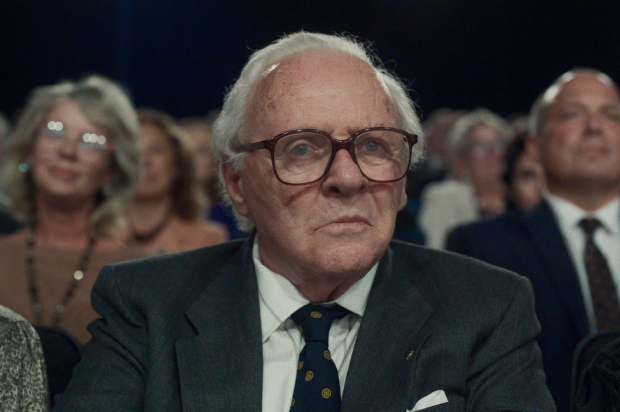

The same goes for the personal drama that has been crammed into the film. Pride is a bit like Titanic, insofar as it has a grand old cast — I counted one Imelda Staunton, one Bill Nighy, one Paddy Considine, one Aforementioned West, and a smattering of actors that you may recognise from the television — and it uses them to recreate a day in the life of the Twentieth Century. But, again like Titanic, it tries too hard to reduce the story to human proportions.

George MacKay is Joe, our guide to this weird world of rubber fetishists and Welsh people. He’s a photographer who is only just waking up to his own homosexuality. What follows feels like a checklist of the young gay experience: first protest, first party, first kiss, first row with parents, first teary departure from his home etc. It’s too cursory and convenient to be properly emotional. There’s little more to the character than the character arc.

As it is, there’s plenty of emotion in the bigger stuff. The film ends with the 1985 Gay Pride march through central London. Turnout hadn’t been great the year before, but this time there were hundreds of new recruits to the cause. There at the front of the procession, behind a LGSM banner, were coachloads of miners and their families returning the favour. Whoop! Talk about a cinematic climax. Even if you cannot abide Pride’s simplistic politics, or its synth-pop soundtrack, it’s a stirring enough conclusion. You’ll laugh, as they say. You’ll cry.

But will anyone spring a leak for the Welsh valleys? Six crow-miles away from the village where Pride was shot is the Cefn Coed Colliery, which closed in the late 1960s and is now a museum. The village itself sits in one of the poorest areas in Wales, where a fifth of the working-age population is stuck on out-of-work benefits. This isn’t 1984, this is now. Perhaps someone should make a movie about that.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in