Nato is taken more seriously in Russia than in the West. Here, Nato is largely seen as yet another international bureaucracy, as useless as the rest of them. But to a former KGB officer like Vladimir Putin, the Cold War has never really ended, and Nato is an exceptionally dangerous and perfidious enemy. You may not criticise corruption in Russia, he says, as that would play into Nato’s hands. Putin had no choice but to invade Ukraine — in the Ukrainians’ own interests, to protect them against a Natotakeover.

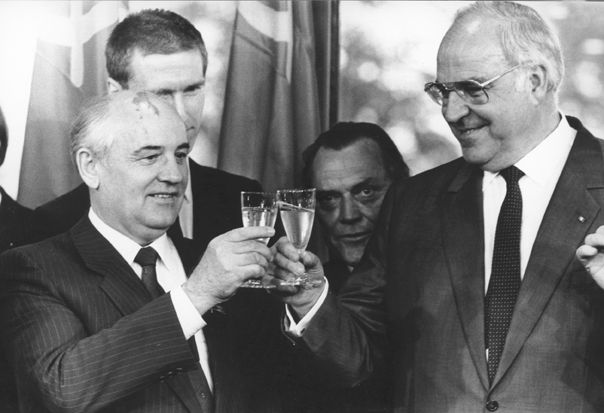

Putin’s case against Nato is that it has deceived Mikhail Gorbachev. Gorbachev says he agreed to withdraw from Soviet central Europe only after being promised that ‘Nato would not move a centimetre to the east’. This claim would seem to be corroborated by the handwritten notes of James Baker, the former US Secretary of State. ‘Nato — whose juris. would not move eastward,’ he scribbled during a conversation with Gorbachev in 1990. He then wrote to Helmut Kohl, Chancellor of Germany, that he had offered the Soviets ‘assurances that Nato’s jurisdiction would not shift one inch eastward from its present position’. Since then, however, as many as ten eastern European countries have joined Nato, and Ukraine seems to be next in line. So Moscow seeks to justify the invasion as no more than a defensive move, taken in response to Nato’s treachery and expansionism.

Baker’s notes and Gorbachev’s recollections are all very interesting, but after all, the Soviets themselves were meticulous note keepers. Every word said by their leaders was recorded, and the transcripts circulated to those who needed to know. If Nato leaders really had given assurances to Gorbachev, the Kremlin would have it in black and white. Ten years ago, it seemed as if these files would be open to the public: Gorbachev’s former aides preserved their own copies, and let historians see them. Putin’s aides intervened to stop this outrageous spreading of state secrets. But not before I had copied the documents and smuggled them out of Russia.

The records show no trace of a promise that Nato would not expand. It’s quite clear that Nato expansion was already on the cards: indeed, Gorbachev was talking about joining the alliance. No promise was broken because none was made. And if the idea of a broken promise is being used as casus belli in Ukraine, it is being used fraudulently.

The records show that, on 25 May 1990, Gorbachev spoke to President François Mitterrand of France, referring to ‘some voices’ in eastern Europe ‘advocating these countries leaving the Warsaw Pact and joining Nato’. He then commented:

My own attitude to such changes is far from dramatic. We have recognised the right of those countries to have such social systems and ways of life as they may freely choose. All the more so since this does not prevent co-operation between us. Let them choose to organise their lives in such forms as they please.

Had Gorbachev demanded assurances of no Nato expansion at the time, they would probably have been readily given. But in fact he demanded the opposite. On 31 May 1990 he told US President George H.W. Bush:

I see your efforts to change the functions of Nato, to try and involve new members into that organisation. If you seriously take a course towards a transformation of the alliance and its political diffusion in the common European process, that, of course, makes it an entirely different matter. But that would raise the question about turning Nato into a genuinely open organisation, whose doors would not be closed to any country. Then, perhaps, we also might think about a Nato membership for ourselves.

On 8 June 1990, Gorbachev told Margaret Thatcher:

Reforming both Nato and the Warsaw Treaty Organisation, and an agreement between them, would lead to a situation when any country would be able to join either of those organisations. Maybe someone else would want to join the Nato. And what if we, the USSR, decide to join the Nato?

On 5 March 1991, Gorbachev told John Major: ‘To subvert Nato from within, we [Russia] are going to write an application to join Nato.’ Major answered: ‘It is better to apply for membership in the European Community.’ To which Mr Gorbachev replied: ‘If we are talking about Europe from Atlantics to Urals, we should look at the military organisations through the same spectacles. You just cannot sit on two chairs at the same time. Parts of you may get pinched between them.’

So where is the naive Gorbachev of the Russian myth, with his gullible acceptance of Nato’s false promises? He was talking of a much wider alliance.

And what of James Baker’s notes? Phrases like ‘not an inch eastwards’ were in fact used in a very different context: an issue which arose out of the unification between West Germany, where Nato troops were stationed, and East Germany, with its Soviet troops. It was agreed that, for a few years’ transitional period, all troops would stay where they were. The Soviets would be given time to prepare their withdrawal, while the Nato troops would not move an inch eastwards into former East German territory.

But there was a bigger deal that Gorbachev wanted (and secured). Nato would be ‘reformed’ into a ‘political’ organisation and open its doors to co-operation with the East, which would result in its eventual ‘political diffusion in the common European process’.

‘If it is not against us that Nato is meant to fight, then against whom? Not against Germany, by any chance?’ asks Gorbachev in one conversation with the US President. ‘As I said, against instability,’ replies Bush.

The promise really given in 1990 was to ‘politicise’ Nato in this way. That promise was faithfully kept, with unfortunate consequences. During the first Cold War, the strength of Nato was its structure as a straightforward defensive alliance. If you attacked one Nato member, you were at war with all others, simple as that. It was this certainty that deterred the Soviet threat and secured peace in Europe for over 40 years. Today, Nato is little more than just one of several international talking shops. It is not keen to spell out what, if anything, it would do if Latvia or Estonia followed Ukraine on to Putin’s hit list.

As Putin actually knows, the West was every bit as good as its word: Nato has been defanged, and is no longer a threat. The consequences of that attempt at appeasement of Russia are now unravelling in eastern Ukraine.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in