Driving up the west coast, from Bridge-town to Speightstown, you soon see why people around here call this the Platinum Coast. It’s not just the colour of the coral sand — it’s the colour of the foreign money. These seafront lots sell for millions, prices few Bajans can afford. Yet once you head inland you encounter another country, a land of chattel houses and plantation houses — remnants of the twin trades that shaped this island, slaves and sugar.

Built on borrowed land, the first chattel houses were purely practical: basic wooden bungalows, easy to dismantle and put up elsewhere. Palatial plantation houses aped their British antecedents — Georgian and Jacobean mansions, impractically relocated. Fittingly, the chattel houses have endured, while many of the plantation houses are hollow ruins. But not all of them. Some of these colonial relics have been lovingly preserved. Recently I went to two of them, and saw another side of Barbados, a world away from the beach bars along the western shore.

First I went to Colleton House, a robust pile on a steep promontory high above the clear blue ocean. It was built by Sir John Colleton, a royalist veteran of the English Civil War. The contents are a rich hotchpotch: modern art in the main house; tribal artefacts in the stables. There’s an ancient cannon outside, installed to guard against invaders. Yet it was the crumbling slave quarters in the lush gardens which lingered longest in my mind’s eye.

We drove on, across the island, to Clifton Hall, on the wild Atlantic, where the owner, a Glaswegian Italian called Massimo Franchi, welcomed us in for a rum punch. Like Colleton House, Clifton Hall dates back to the 1600s, but here the mood is much more homely. He’s renovated it beautifully, right down to the mahogany doors. The walls are brightly painted, reflecting the vivid hues outside. Yet like every plantation house, this place harbours a dark secret. Upstairs is a bare room with a bolted door. Massimo believes it was built to house a mad relative. He hasn’t changed a thing.

I wouldn’t have found half this stuff without Cobblers Cove, the hotel that put me up and guided me round the island. A discreet bolthole on the wealthy west coast, hidden between lavish villas and opulent apartments, it’s more like a private members’ club — quiet, quaint and understated. It feels a bit sleepy, but that’s just the way I like it. Their local contacts are unrivalled. The staff all speak their minds. The house was built in 1944 but it feels far older. The family who own it are descendants of Sir John Colleton.

On my last day in Barbados I went shopping in Bridgetown with Cobblers’ head chef, Michael Harrison, who used to work under Michel Roux at La Gavroche. We bought mahi-mahi in the fish market and plantains in the vegetable market, and he cooked them for me, beside the sea, on an open stove.

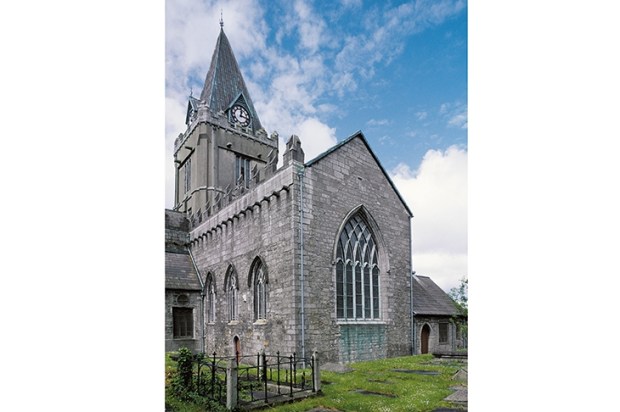

I walked up the beach to St Peter’s Church, founded in the 17th century. The building was full of people. The Anglican service was immaculate; we sang all the usual hymns. The sermon, about slavery, was one of the best I’ve ever heard.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in