Even ardent Mitfordians must quake at the sight of yet another biography of the sisterhood. There have been more forests felled in the name of Nancy, Pamela, Diana, Unity, Jessica and Deborah Freeman-Mitford than the Brontë sisters. Jessica alone produced two volumes of memoirs, Hons and Rebels (1960) and A Fine Old Conflict (1977); her collected letters (Decca, 2006) came in at a thumping 700 pages and in 2010, Irrepressible, Leslie Brody’s biography of Jessica’s years in the United States, appeared. ‘Enough already’, one can hear her American sisters cry.

Yet with Churchill’s Rebels, Meredith Whitford, a South Australian author of historical novels, has brought a clear eye and a fresh pen to the early life of Jessica and her first husband, Esmond Romilly. Despite the title, Whitford has, in her very first sentence, set us straight. Esmond was in fact the nephew of Clementine Churchill (his mother, Nellie Romilly, née Hozier, was her sister), not Winston’s, although the latter nobly played the role of uncle to his wayward nephew. Nellie was also a first cousin (there is a strong suggestion that she was half-sister) of Jessica’s father, David Redesdale. Cousinage and sisterhood intensified.

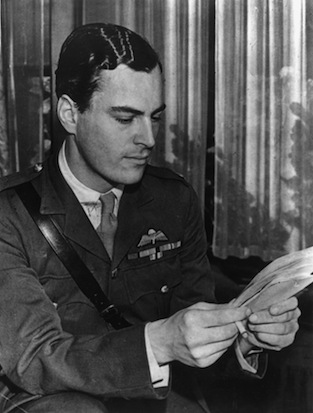

The intensity was all the greater given how briefly the lover-cousins were a couple — from February 1937, when, within a week of their meeting, the teenagers eloped to Spain, until June 1941, when Jessica was in America and Esmond, having trained in the Canadian airforce, was posted to Bomber Command — a mere four years and four months of escapes and scrapes. He disappeared in a bombing mission over the North Sea on 30 November 1941. And with Esmond’s death, Whitford’s story ends. Mitford spouses rarely score equal billing, but Whitford seems keen to rescue Romilly from the bad press he has had in the Mitford canon. Not only did he cut their Decca off from them, but he failed to succumb to the rest of the brood’s famed charm.

Romilly’s fervour, his courage and his love for his wife shine through, but despite the author’s efforts, or perhaps because of her devotion to the facts, his opportunism and great ability to hate fail to make this shooting star lovable. Jessica had these traits too, but she had another 55 years to establish herself as an unmitigated Mitford — an eminently readable author, but also, in her case, a celebrated crusader and much admired muckraker.

Despite her semi-exile in California and lasting estrangement from her father and her fascist sister Diana, Jessica’s ties with her family were vital, although sometimes volatile, as Charlotte Mosley’s superb collection of the sisters’ correspondence shows. Her relationship with the Hitler-besotted Unity was fascinating, reflecting the whole family’s unwavering affection for her. While Jessica’s contempt for the beautiful, clever Diana never softened, she loved her ‘Boud’, despite her contemptible views. One look atbrain-damaged Unity’s pathetic letter to Jessica in February 1940 (reproduced by Whitford) immediately puts any doubt on that score to rest.

Deborah, the youngest sister, who died last week, said of a favourite family biographer, Mary Lovell, ‘She is a terrier for research.’ Whitford, too, has scrupulously thumbed through the crowded shelves of Mitford myth and folklore and convincingly challenges a number of episodes that have previously cast Jessica in a poor light.

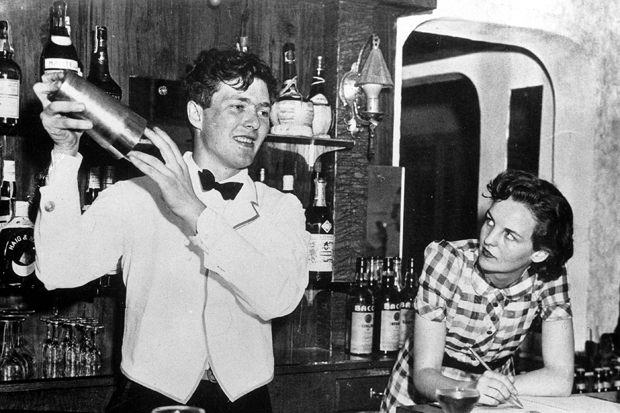

She presents some vivid vignettes: Nellie Romilly and her mother, Lady Blanche Hozier, at the gaming tables in Dieppe; Jessica’s first demonstration, ‘Down with the Baldwins’, in support of Edward VIII; the young couple’s first — and only — row, as Esmond attacks Jessica for her ‘upper classishness’ after her furious response to a local man who beat his dog in a Spanish café; how, in their brief time in Rotherhithe, every light and appliance blazed day and night but the resulting electricity bill was completely unexpected by the unworldly pair (among their ruses to avoid paying was to lie in bed, as Esmond believed it was a violation of Magna Carta to serve process on people in bed); the rebels being waved off by Nanny as they sailed for a new life in America; and, once there, how around the table of the Washington Post publisher, Eugene Meyer, who was proclaiming the British incapable of theft, everyone turned to Esmond to find him stuffing his pockets with his host’s cigars. Chancers and spongers they both were — but patriots and altruists too.

Esmond’s bravery and pluck and Jessica’s ebullience and wit make them riveting subjects. Yet the real heroines of Whitford’s book are their mothers, Sydney Redesdale and Nellie Romilly, the former so detached, the latter so smothering, but both steadfast in their love and support for their rebellious offspring.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £11.95 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in