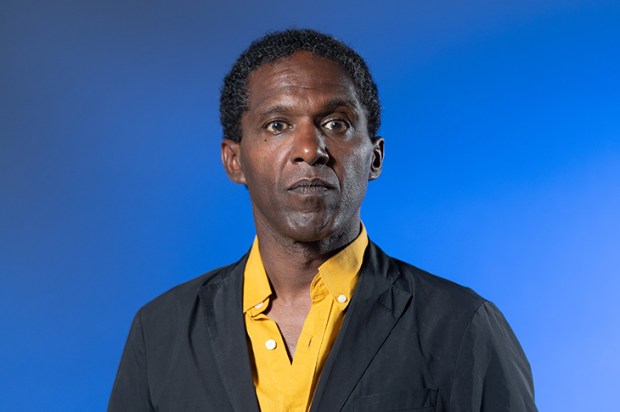

The new controller of Radio 3 has at last been appointed. Alan Davey (not to be confused with the former bassist from Hawkwind) comes to the BBC from the Arts Council and a career in the Civil Service. This will be his first job in broadcasting, and will be no small challenge. These are tough times for Radio 3, squeezed between the commercial charms of Classic FM and the trendy allure of BBC’s 6 Music, and, worryingly, in the last quarter its audience numbers went below 1.9 million for the first time since 2010.

The BBC’s home of classical music and ‘culture’ is often criticised for being too off-putting, too elitist, not in tune with the current mood. Critics like to ask why, with just under two million listeners, the station should continue to be funded by UK taxpayers, most of whom will never tune in to hear Matthew Sweet or Philip Dodd on Free Thinking or to Opera on 3 live from the Met in New York.

At the other extreme, some formerly loyal listeners (including, I suspect, more than a few readers of this magazine) have been complaining that Radio 3 has gone too far down the populist road, breaking up its morning sequence with chit-chat and gimmicks such as the classical top ten and nerd-ish interactive quizzes, which ask listeners to phone in with their answers to questions such as identifying a piece of music after hearing it being played backwards on the rewind button.

Davey has referred to his new job as ‘an honour’, especially because of his remit ‘to renew’ this ‘wonderful institution’ for ‘the digital age’. But what does renewal imply? What kind of digital new life does Radio 3 need?

Last week’s offering from the newly created super-channel BBC Music, an umbrella organisation in charge of all the BBC’s musical output under the control of Bob Shennan (also the controller of Radio 2), was a digitally remastered version of the Beach Boys’ inimitable ‘God Only Knows’, performed by 27 international artistes and played simultaneously at eight o’clock last Tuesday night across most of the BBC’s radio stations and TV channels. Radio 3’s listeners were saved from the trauma of hearing that ethereal, haunting song given new digital life by the likes of Elton John, Stevie Wonder, One Direction and Nicola Benedetti because at the time it was hosting a ‘live’ concert from St George’s Bristol and could not be interrupted.

Years ago, when digital editing was just taking off, ‘Perfect Day’ was similarly re-created by a cast of unusual cohabitees for the BBC’s Children in Need campaign. This, though, wasn’t claimed as ‘a unique, impossible performance’ (the less than inspiring tagline for ‘God Only Knows’). Nor was it anything more than part of the charitable campaign. In contrast ‘God Only Knows’ appeared out of nowhere and as part of nothing, and little was said about the fact that the recording is also being sold to raise money for charity. On the contrary, the BBC appeared much keener to show off its ability to pull in the superstars whenever it wants. How much, I wonder, was spent on this extravagant enterprise, money that could have been spent on truly inspirational programme-making?

As Ian McMillan asked last week on The Verb (Radio 3, Friday), ‘Is there any other radio station in the world apart from Radio 3 where you could talk freely about the anacoluthon sentence?’ He meant it not as something to be ashamed of, but as a celebration of 3’s perverse delight in the little-known, the forgotten about, the hinterland of knowledge. McMillan himself can hardly be accused of being highbrow, metropolitan or exclusive. His own poetry is rooted in the everyday, the matter-of-fact; direct and easy of access. His strong devotion to his native Barnsley is echoed in his distinctive accent. His 45-minute ‘cabaret of the word’ discussed the ways in which our subconscious will find itself an outlet for what it needs to reveal, talking to the poet Simon Armitage and the psychotherapist Jane Haynes.

How does this link up with the anacoluthon sentence? (No, I hadn’t a clue either.) Poems are negatives, says Armitage; they describe the absence around things, not the thing itself. ‘I’ve told you what it isn’t what I am saying it is.’ The anacoluthon sentence, to be a little more precise, is ‘a crack in the window of grammar’; it’s a change of direction in meaning or description, a sudden turn, that has no immediate warning, although there will always be a clue.

Why is such a linguistic tool useful to Haynes? Because the unconscious doesn’t like to reveal itself. It does its best to elude us, but at times we will find ourselves saying more than we intend, usually not in words, but by suddenly changing the direction of thought. In that turn lies the meaning. I was listening in my car and on arrival found myself switching off the engine but not opening the door, unwilling to leave behind the warm, enthusiastic company of McMillan and his guests.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in