Kenya

I perused the brochure produced by Tanzania’s state corporation for livestock ranching, aimed at attracting foreign investors. Under ‘beef production’ was a photo of an American bison. Tanzania’s state bureaucrats might not know what cows look like — but they still know how to eat them.

My father Brian Hartley had 3,500 cattle when socialist president Julius Nyerere nationalised our ranch on Kilimanjaro’s slopes. In the 1960s, Nyerere seized farms in ways Mugabe never dared emulate. I still have the note Nyerere scrawled in biro, taking my father’s business partner’s property within seconds of arriving there.

Eating began immediately. Dad stayed on to manage his former farm because it was home — but Nyerere’s men arrived regularly to show Communist bloc comrades the fruits of revolution. ‘Bring meat!’ they ordered. After a year of butchering steers, Dad left in disgust.

The borehole that had yielded 1,500 gallons an hour broke. Stuff got stolen. Britain and Sweden poured in aid money to fund experts to rehabilitate the ranch. Around 1996, when my family scattered Dad’s ashes on the farm where his heart had always been, the cattle herd had declined to 1,665. They were no longer the pedigree animals Dad had selected as a judge of Boran cattle at the breeders’ shows.

In 2010 I visited the ranch with my sister Bryony and found there were 229 cattle left. They were inbred, swivel-eyed, low-grade things with horns but no hindquarters. On the film Bryony took of the derelict house our parents built, you can hear her sobbing. Workers with fluorine-blackened teeth were living in the stables. Charcoal burners were hacking down the forest. The grazing was gone and dust swirled beneath snowless Kilimanjaro’s dome. Where rhino and lion had once been common, now only spring hares hopped. The farm vehicle had no wheels.

In Dar es Salaam, the state corporation’s manager expressed consternation. He had never visited the farm but had understood there to be thousands of cattle. A government auditor’s investigation later failed to decide why so many animals had been ‘lost’.

The government was advertising for partners to revive the farm. ‘We are making a quantum leap,’ the manager said. ‘We need only serious investors.’ My brother Richard and I applied and won the tender covering an area of 25,000 acres. This was after lawyers advised against suing for compensation or the return of Dad’s farm. ‘Don’t bother,’ they said.

‘You’re mad,’ my mother said. ‘Do you know what they did?’ ‘These people have set it up almost as if they want it to fail,’ said a friend who farms in Tanzania. But for more than a decade I have been optimistic about Africa. I have believed in what they call ‘Africa Rising’ — the idea that we are the Next Big Thing. I pressed on not through sentimental need to resettle land dusted by my father’s ashes, but more because I knew we could make a success of land we loved.

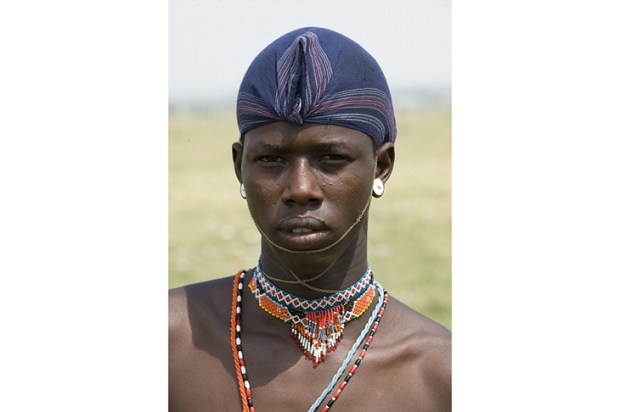

The manager led a delegation of officials to my farm in Kenya. They got cow shit on their city shoes and suits. They took photos of each other posing amidst the Boran cattle herd I’ve built up myself in a country that always welcomed us without ‘eating’ our stock.

The officials seemed disappointed to hear ranching is a tough business. Forget, I said, the dreams of dividends, of air-conditioned vehicles, meat sizzling on barbecues. My parents lived frugally with hurricane lamps and an outside loo. And now with everything destroyed we were going to have to start again from scratch.

We started spending what was going to be a large sum of cash. We even agreed to pay the state corporation’s bills on valuation, surveys and other paperwork to sell 51 per cent of Dad’s farm back to us.

Four years passed. ‘Be patient,’ I told myself. ‘Things happen slowly in Tanzania.’ I asked to see the farm books. None existed. No audited accounts were ever produced. Occasionally, the manager asked me urgently to rush him a document to be presented to cabinet, since this was being discussed at the highest level. I made repeated visits to Tanzania. Nothing happened, but I always recalled my friend saying, ‘They’ve set it up as if they want it to fail…’ The manager wrote to say the police had taken a large chunk of the farm for use as a firing range — pity those spring hares. A second section of excellent land was removed to build tele-phone towers and government offices — in the middle of nowhere. A third area was to be cut off to give away to unknown persons for cultivation.

Not only had the cattle been eaten or ‘lost’. Now the land was being eaten away too, like a cookie nibbled at the edges — or should I say a beef kebab. What happened to 3,500 cattle and the farm? Gone, like the snows of Kilimanjaro.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in