To the British embassy in Paris for a colloquium on ‘Napoleon and Wellington in War and Peace’ organised by our ambassador, Sir Peter Ricketts, to mark the bicentenary of the purchase of the embassy from Pauline Borghese, Napoleon’s sister. (According to the historian of the house, Tim Knox, Pauline would warm her feet on the naked backs of her ladies-in-waiting, and be carried to her bath by a huge Egyptian slave.) William Hague opened our proceedings, boldly pointing out the other anniversarial elephant in the room: it was Trafalgar Day. The French fielded several of their senior Napoleon historians, including Jean Tulard, Thierry Lentz of the splendid Fondation Napoléon, Jacques-Olivier Boudon and Talleyrand’s biographer Emmanuel de Waresquiel, while Britain was represented by Peter Hicks (who spoke in French), Philip Mansel, John Bew, Wellington’s descendant the Marquess of Douro, and myself. If you’d like to hear the resulting avalanche of wit, charm and civilised scholarly debate, please go to this site.

By contrast, more than a thousand people turned up to Intelligence Squared’s debate at the Emmanuel Centre in Westminster to watch Adam Zamoyski and me debate the motion ‘Napoleon the Great?’, partly I suspect because it was moderated by Jeremy Paxman. As we left the Green Room for the main hall, I overheard Jeremy saying to Adam, ‘Let’s bury this maniac’, which I assumed referred to Napoleon. When Jeremy started off by making a rude reference to Napoleon, I pointed out that in his recent book Empire he’d referred to him as ‘a despot’. ‘But he was a despot!’ expostulated Jeremy. ‘Ladies and gentlemen,’ I said to the audience, ‘the moderator.’ Napoleon went on to win 56 per cent of the vote, despite Adam’s superb 15-minute speech with no notes.Publicising my book will involve speaking at well over a dozen literary festivals, and they are a pretty mixed bag. The big ones such as Cheltenham, Hay-on-Wye, Edinburgh and the splendid new BBC History Festival in Malmesbury guarantee large audiences, with lots of people willing to buy books. With the smaller ones, it can be pot luck. I once spoke at the Sevenoaks literary festival, where fewer people turned up than there were oaks. I suggested that we all go out to dinner at a local Indian or Chinese restaurant but they were having none of it, and insisted I deliver the speech to four people in exactly the same way as I would have if it were 400.

The editing of this book has been an extraordinary intellectual exercise, due to the omnivorous brain of my editor at Penguin, Stuart Proffitt. Among the scores of questions he asked me in the first sets of edits were: ‘How wide was the river Po in 1796?’, ‘Did Napoleon take Herodotus to Egypt?’ and ‘Was Napoleon conversant with the astronomical theories of Herschel?’ Still, that was better than in my last book, where he asked of one gag of which I was particularly proud, ‘Are you sure this joke is funny?’ At lunch at the Paris colloquium, five of us around the table realised we were all edited by Stuart, and started swapping editing stories. I won’t mentioned the name of the extremely distinguished historian who revealed that in the margin of the peroration part of the conclusion of one of his books, Stuart had written: ‘Bit cheesy.’

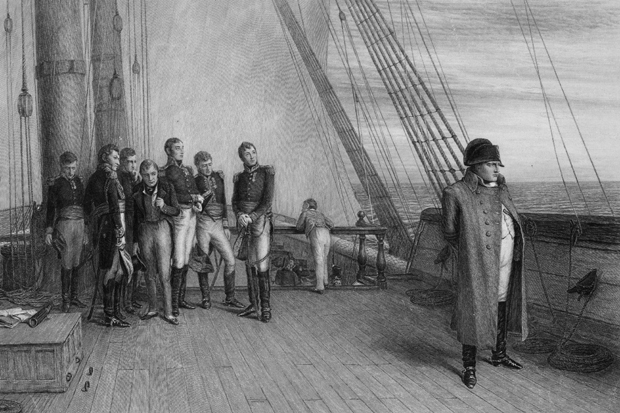

The only way to visit Longwood House on St Helena, where Napoleon was exiled and died, is to spend six days on the Royal Mail packet ship from Cape Town, during the course of which you don’t see a single ship, plane, fish or bird the entire time. The BBC crew I was travelling with and I took part in the ship’s quiz every evening, which I’m pleased to say we won. (First prize: a bar of Cadbury’s Fruit & Nut.) It was a little disconcerting when the question was posed ‘How many valves has the heart?’ and the team that included the ship’s doctor said two, whereas the correct answer is four.

One of the more outré theories about how Napoleon died is that he was poisoned by the arsenic in the wallpaper at Longwood, a notion that I rather pooh-pooh in my book. A few months ago I bought at auction a piece of the wallpaper that hung in the room in which he died, but, committed though I am to historical research, I’m not about to give it a lick. If any reader is prepared to, please get in touch. Another, less potentially lethal, way that Spectator readers might be able to help the cause of historical research is if anyone can explain a reference that has so far eluded scholars. Napoleon occasionally in letters referred to Josephine’s private parts as ‘the Baron de Kepen’, but who was he, and why did he provoke such a reaction in the Emperor?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

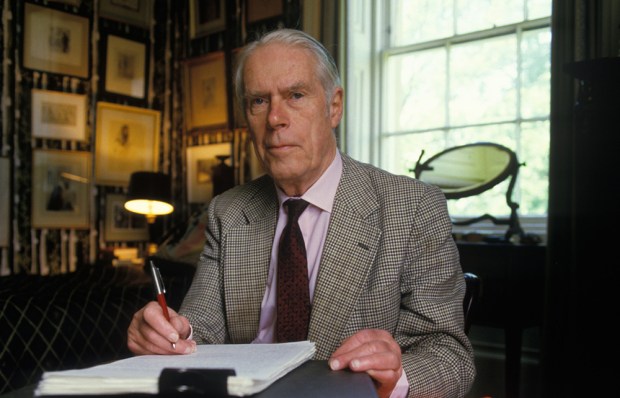

Andrew Roberts, just published Napoleon the Great. His other biographical subjects include Lord Halifax, Lord Salisbury, Hitler and Churchill.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in