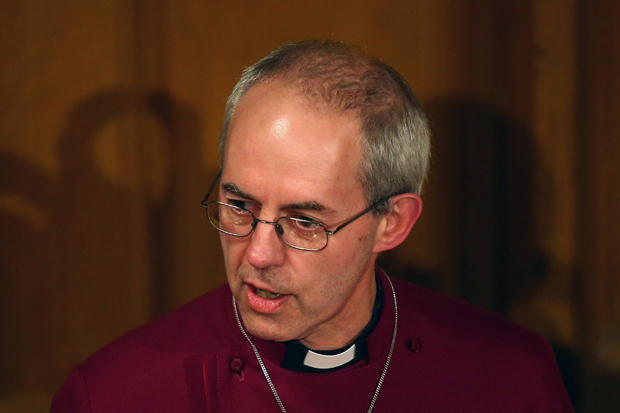

For decades, interventions of the Archbishop of Canterbury in national debate were like a sporadic bombardment of small pebbles against the door of Downing Street. Justin Welby has changed all that. This week, payday loan companies are facing reform (or in some cases oblivion) as new caps on interest payments come into effect. That the industry finds itself in this position is thanks, in no small part, to it having been hooked around the neck by the Archbishop’s crosier.

Welby has inspired reform of the industry not by trying to set himself up as the leader of the opposition in a cassock, but by acting as an effective leader of the Church of England. His approach to the payday loan industry was not to demand that it be banned, he being aware that an even darker industry of doorstep loan sharks would replace it, but to compete with it head on. He took the church to the needy by supporting credit unions which will do the job of Wonga but without annualised interest rates of 5,853 per cent and threatening letters from fictitious firms of lawyers.

Welby’s intelligence on financial matters stands in direct contrast with that of his predecessor, Rowan Williams, whose pronouncements on current affairs so often came across as those of a lofty professor who had found himself in the wrong lecture hall. Straying from divinity to economics in a piece for this magazine in the middle of the 2008 banking crisis, Williams resorted to a generalised attack on markets and went on to demand a ban on short-selling. This rather missed the point that the traders who had been making money short-selling the shares of banks were only able to do so because they had spotted that the banks were in trouble before anyone else had. Their activities were a symptom, not a cause, of the banking crisis.

Justin Welby, who of course had a career in business, would never resort to the bizarre charge that markets are malign in themselves. On the contrary, he recognises that the church operates in a market of its own, competing for souls. He is from the Church of England’s evangelical wing, which is growing, and his calls for local churches to support credit unions and work with the Treasury on reforms to payday lending are themselves a kind of evangelical mission which, while not necessarily expanding congregations on sink estates, does much to demonstrate how financial services can be harnessed as a power for good.

Welby’s has been a serious voice on banking matters — one which has been lacking in Parliament. Bankers are not evil, he said of his highly successful time serving on the banking commission, they just made a classic and unsophisticated error of borrowing short and lending long. Few in the City could argue with the analysis, yet no one in government has really appreciated this and come up with a credible plan to stop the same thing happening all over again. This is perhaps no surprise, given that government, too, has been borrowing short and lending long: keeping its finances propped up with short-term bonds while committing itself to huge pension payments and the like many decades into the future.

Welby is one of the few voices from a position of power and influence who has expressed concerns about quantitative easing. He is one of the few figures, too, who sees what’s wrong with trying to pump up the bailed-out banks into something approaching their former glory. Instead, he has suggested seizing the opportunity to break them up to create regional banks attuned to the needs of the Wonga classes.

In temperament and approach to matters of religion, Justin Welby is less like Rowan Williams and more like his Catholic opposite number, Pope Francis. Both are modernisers who have ended the carping about their respective institutions being out of touch with the real world and yet who have done so without compromising the values upon which their churches are founded. Rowan Williams often seemed to behave more like an interfaith outreach worker than an Archbishop, bizarrely trying to speak up for sharia law (something which many British Muslims came to this country to escape), and only this week he made headlines again by suggesting that anxiety about schoolteachers wearing full-face veils was ‘misplaced’. Welby, by contrast, has not shied away from speaking out against persecution of Christians in many parts of the Muslim world — and he speaks from his own experience of working in Africa.

No one has condemned homophobia more effectively than Justin Welby. Yet never has he strayed from the view that marriage is defined as a union between one man and one woman and that the state has no right to try to change this. How favourably this contrasts with David Cameron’s politically opportunist pitch for liberal-left votes.

The Tory leadership has been caught out many a time by Welby’s independence of mind. Perhaps because his mother was an assistant to Winston Churchill and he is the great-nephew of Rab Butler and an Old Etonian to boot, the government assumed him to be a dependable Conservative, and has been caught out by his refusal to conform. Downing Street officials have been known to call Lambeth Palace to complain that they have not been given advance warning of his speeches, as if he were a government minister or Conservative candidate.

He is, of course, neither — and nor is he Her Majesty’s Opposition. His political skill has been to place himself in a position in which both main parties believe him to be on their side. At a time when no politician is able to give leadership on moral issues, we have an Archbishop of Canterbury with the intelligence and judgment needed to exert proper power and influence. Once again, Lambeth Palace has become worth listening to.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in