I received a phone call the other day that I wasn’t expecting. It was a BBC producer calling about a Radio 4 series called Great Lives, presented by Matthew Parris. Each week, a distinguished guest is asked to nominate someone they believe is truly deserving of the title ‘Great Life’ and then they come on the radio to discuss that person, along with an ‘expert’.

I got rather excited as she was explaining this. Had someone really nominated me? When she told me the name of the guest I was even more thrilled — Brian Eno, the founder of Roxy Music.

‘The rock legend?’ I said. ‘That’s awfully flattering.’

‘Yes, isn’t it?’ she replied. ‘And we were wondering if you’d like to be our studio ‘expert’?’

‘Yes, delighted, obviously. [Pause.] But, er, hang on, wouldn’t that be a bit odd?’

‘No, not at all. You are his son, after all.’

The penny dropped. Brian Eno hadn’t nominated me. He’d nominated my dad.

I was happy to do it, obviously, but I also felt a pang of jealousy. In 50 years’ time, would anyone as talented and famous as Brian Eno nominate me for similar treatment? Matching my father’s accomplishments, with only 30 or so remaining, seems a distant prospect.

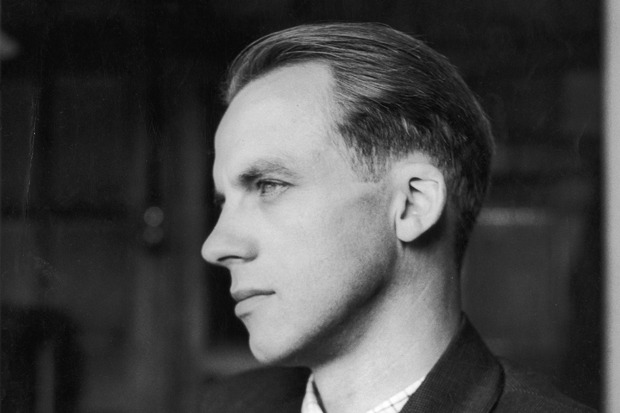

Michael Young was born in 1915, the son of an Irish bohemian painter and a Daily Express journalist. He had a miserable childhood, being packed off to the sort of prep schools that George Orwell wrote about in ‘Such, Such Were the Joys’, but was saved at the age of 13 by a fairy godmother in the form of Dorothy Elmhirst, an eccentric American millionaire. She had started a school in South Devon called Dartington Hall that was the only school in England that taught fruit farming. As luck would have it, my father had a rich Australian uncle with a fruit farm who offered to pay the fees.

Dorothy and her husband Leonard, a Yorkshireman, more or less adopted Michael. Instead of sending him home in the summer holidays, they took him with them on their annual jaunt to America and treated him like one of their own. He travelled in a first-class berth on RMS Aquitania, learned how to sail on Martha’s Vineyard and, on one memorable night, dined at the White House with Franklin D. Roosevelt. When he left Dartington at the age of 18, Dorothy set him up with a small trust fund, as well as a lifetime’s supply of Sobranie cigarettes.

Michael’s first notable achievement was writing a pamphlet for a pressure group called Political and Economic Planning at the age of 22, in which he argued that if war broke out the government mustn’t delay introducing conscription. Churchill read it and was so impressed that he immediately offered my father a job as his private secretary. He accepted, but the offer was withdrawn when Churchill discovered he was a member of the Holborn branch of the Communist party.

Michael went on to run the Labour party’s research department and, in that capacity, wrote the 1945 Labour manifesto. He spent the next six years at the heart of the Attlee government, laying the foundations of the welfare state, then left in 1951 to do a PhD at the LSE. His doctorate formed the basis of a book called Family and Kinship in East London which, to this day, is referred to by sociology students as ‘Fakinel’.

But it was his next book that really made his name — The Rise of the Meritocracy. A dystopian satire in the same mould as Brave New World, it purported to be an historical essay written by an academic in the mid-21st century about the emergence of a new ruling class whose claim to power was based on their superior intellect. The book was intended as a satirical critique of what my father regarded as a pernicious way of justifying inequality and it irritated him for the rest of his life that the word he’d coined to describe this ghastly new phenomenon — meritocracy — was generally used by politicians to describe something wholly desirable.

At this point, Michael’s place in the history of post-war Britain was guaranteed, but he was just getting started. He set up a research institute in Bethnal Green that, for the next 50 years, became a kind of organisational supernova, pumping out an endless stream of new institutions: the Consumers Association, Which? magazine, the Social Science Research Council, the University of the Third Age, the School for Social Entrepreneurs, Grandparents Plus… it goes on and on. The historian Noel Annan compared him to Cadmus, the founder of Thebes in Greek mythology: ‘Whatever field he tilled, he sowed dragon’s teeth and armed men seemed to spring from the soil to form an organisation.’

And if you think all of that is impressive, he also co-founded the Open University. Whenever I’m at risk of feeling a little too pleased with myself because I’ve helped set up a handful of schools, I remind myself that Michael helped establish the single largest educational institution in the world. At any one time, the Open University has a quarter of a million students, an astonishing figure.

I was the product of Michael’s second marriage and shared a home with him for the first 18 years of my life. At the time, I thought he was a great dad, a figure of towering authority, but now that I’m a father myself I realise how little time he spent with his children. I can clearly remember playing football with him in Waterlow Park on my ninth birthday. A lovely memory, to be sure, but the reason I can recall it is because it was one of the very few occasions he took me to the park. My children, by contrast, will have no specific memories of playing football with their dad, because we do it every weekend.

For Michael, the work always came first. He’d been given a great gift by Dorothy Elmhirst, who’d saved him from neglect, and that left him with an overwhelming sense of obligation to do the same for others. If I’m going to achieve anything else in the next 30 years, it must be driven by the same philanthropic impulse.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Great Lives: Michael Young will be broadcast on Radio 4 on 23 December at 4.30 p.m. and repeated on Boxing Day at 11 p.m. Toby Young is associate editor of The Spectator.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in