A new year must start with hope and resolution, and if you’re very rich, with influence in the highest places, I’d urge you to resolve to dust off the private jet and get to Paris quick this weekend hoping to find a ticket somehow for the last Châtelet performances of An American in Paris, Christopher Wheeldon’s s’wonderful, s’marvellous new staging of the Gershwin/Minnelli musical film. Or book for New York in March when the show moves to its second home on Broadway. But surely there must be a UK run soon.

It’s the first big dance-musical of the Royal Ballet’s favourite son, which is why we should pay attention. The secret of Christopher Wheeldon’s current status at 41 as blue-eyed boy of the Western ballet world is his geniality. Geniality is not the first quality necessary in a great choreographer (Balanchine, Ashton and MacMillan were not longing to be loved, they were insistently asking questions about dance’s theatrical potential). When he was younger he wasn’t so genial, he was more questioning, and he looked like a genius in the making. It would be regrettable if his edgy, superbly graphic Ligeti ballets, Polyphonia and Continuum, of 2001 and 2002, were to be lost in the welter of happy-foot stuff like Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the pointlessly decorative Wheeldon offering by the Royal Ballet this Christmas, and the recent sense of recycling in his work.

But the gift for joyfulness that he shows in An American in Paris will make a larger public equally grateful (and after all MacMillan, Balanchine and Ashton did musicals too). Moreover we saw in Wheeldon’s intriguing Royal Ballet creation last spring, The Winter’s Tale, that his initiation into dance theatre had taught him a thing or two about ballet stagecraft too.

For me, his staging trumps the Vincente Minnelli film, which has a back-of-an-envelope feel to its assembly of Hollywood archetypes (plus you really have to like Gene Kelly’s determined goofiness). Now the characters find themselves in the newly liberated Paris of 1945 and the theme of reawakening extends to them, as well as to the city.

The designer Bob Crowley exactly refracts this in brilliantly simple cutouts and sophisticated video projections (classic Paris from the Eiffel Tower to the Seine), which quickly shift between scenes like he’s riffling through news photos or the sketches pouring from GI Jerry Mulligan’s pencil as he wanders the city insouciantly enjoying civilian life at last. It’s a masterly response by Crowley and his lighting associate Natasha Katz to Craig Lucas’s thoughtful revision of the book — the sense of place and time has a newly touching credibility.

Some zingy new repartee results from being more upfront about the Jewishness of Lise and composer Adam, and the gayness of Lise’s fiancé, Henri. The lovable American art patron Milo — a scene-stealing performance by West End familiar Jill Paice — takes a poignantly sophisticated attitude to her discovery that her money can’t buy love. And the many jokes about Americans’ terrible French go down enormously well with the Paris audience reading the French surtitles.

Still more, arranger Rob Fisher gives us a luxury banquet of George Gershwin’s poignancy and zest, realistically expanding the film score with the piano concerto and Second Rhapsody for a smallish live band.

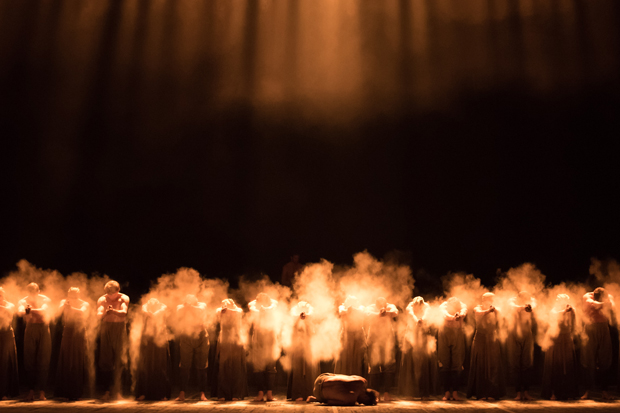

Within this top-notch setting Wheeldon proves refreshingly daring in his stage-writing. By making Lise an aspiring dancer, the opportunities for dance inside the action abound. That includes the jazzy as well as his trademark crisp neoclassicism (though the eponymous 17-minute ballet is less interesting of itself, partly because this ‘Châtelet Ballet Company’ isn’t New York City Ballet). But it’s the deceptive casualness of the rest that’s the revelation. Moving actors, dancers and mobile scenery interactively within a story’s theatrical rhythm is a challenge, and Wheeldon’s got that rhythm.

‘I Got Rhythm’ itself is one of many highlights, set in a blackout with syncopations of snapped matches and drummed spoons, and there’s a near-Puccinian letter-writing quartet in which Henri haplessly tries to word a proposal letter to Lise, while she writes to her mother about her doubts on this marriage, Jerry and Milo adding their own independent troubles. Which leads to Lise alone and ‘The Man I Love’. What could be nicer?

Wheeldon has excellent casts: two real dancers for the leads. Our own Royal Ballet ingénue Leanne Cope is the unaffected, lovable Lise, singing with plaintive beauty and dancing better than Leslie Caron; but New York City Ballet’s Robert Fairchild is the motor of the show, dancing up a storm, and a more than decent singer. He’s smart enough to let Jerry’s shallowness shine through, in contrast with the hidden depths revealed in others. All of which will yield great rewards for other casts worldwide. This is happy news for Wheeldon-watchers. Grab that jet.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in