If like me you get all your news from the Cornish Guardian, you may have spotted an article announcing that the Fairy Investigation Society is conducting a survey. They’re seeking information from anyone who has seen any pixies, elves or sprites — all on a strictly anonymous basis. I rang the man behind the research and he told me that in just three months, he’s had over 400 replies. An example: ‘I was walking down a field in Scotland when I noticed a winged being leaning up against the side of a sycamore tree. He was as tall as the trunk, maybe 15 feet.’

You might laugh it off, but the man was deadly serious — as are his informants. Well into the 21st century, beneath the radar of a popular culture obsessed with vampires and aliens, elements of traditional British folklore have inexplicably survived.

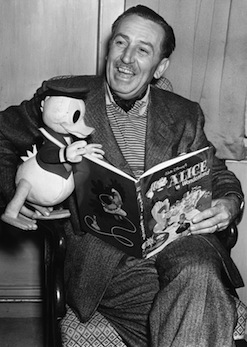

A century ago, discussion of the little folk was quite common. The Fairy Investigation Society was founded in 1927 by a group of spiritualists and, legend would have it, attracted such illustrious members as Walt Disney. Its true believers were delightful eccentrics of a very English stripe. Marjorie Johnson, eventually secretary of the society, encountered an elf in her bedroom as a child and grew up to be a committed fairy-hunter. In the post-war years, she assembled a remarkable archive of sightings — including a family of gnomes in Wollaton Park who were observed driving about in small racing cars. Miss Johnson intended to publish her magnum opus but was undone by some unguarded comments to a tabloid. ‘It has taken me years of study to win their friendship and discover the secrets of their sex life,’ she told the Sunday Pictorial. ‘But anyone who is admitted to the circle of fairy friendship is very fortunate. Through billions of years fairies have learned the secrets of universal love.’

It is thought that this tabloid scandal encouraged this sweet lady to retire from public life, and her fellow fairy-hunters to retreat into the closet. What little research took place thereafter gained scant attention. We owe much of what we know about Hikey Sprites thanks to the dedicated investigations of one Ray Loveday, who travelled East Anglia asking strangers at bus stops if they had ever seen any. A reviewer of his excellent pamphlet, The Hikey Sprites: the Twilight of a Norfolk Tradition notes that Mr Loveday’s research was sadly restricted by the limitations of the local bus route.

Though Britain stopped openly talking about fairies, faith in them remained. Dr Simon Young, the academic conducting the fairy survey, says that sightings still occur even though the look of fairies changes according to popular tastes. Until the Victorian era fairies were flightless and often regarded as amoral — even mischievous. Indeed, when I told a Catholic academic friend about the Fairy Investigation Society he insisted that fairies were demonic. ‘The best thing you could do if you encounter a fairy is step on it,’ he said, ‘or lay down slug pellets.’

Since Disney began to do PR for fairies, a significant number of sightings feature creatures who bring a sense of peace; however, there are also reports of gnomes, a walking tree and ‘a group of creatures, maybe 25cm tall, humanoid, hairless, with spindly limbs and slightly shiny leathery skin’ that ‘wore nothing but Oxford commoners’ gowns (no mortarboards)’. The best encounter is that of a teenager camping on the moors who went behind his tent to relieve himself only to discover that he was not alone: ‘when I looked down [there] appeared silhouetted a small shape with his hands on his hips, I could see it by a faint light coming through a large hole behind him in the hedgerow. I got the impression of someone very angry. This scared me and needless to say I could not do what I intended. Slowly backing away I quickly apologised (sincerely believed I had almost pissed on a wee folk).’

Are some of these stories are tongue-in-cheek? Maybe. Nevertheless, there’s charming sincerity to many of the tales and to the work of Dr Young in general. ‘I don’t know what’s going on,’ he told me. ‘But perhaps it indicates in part that the countryside has a presence.’ I think he’s right. I very much doubt that hedgerows are home to thousands of magical creatures, but it’s true that the countryside is magical and that the British relationship to it goes well beyond the physical and into the spiritual — which is why should preserve it as passionately as the fairy-hunters seek to preserve our folklore.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in