In December 1817 Benjamin Robert Haydon — vivid diarist and painter of huge but inferior canvases of historic events — held a Sunday luncheon to which he invited John Keats, Charles Lamb and William Wordsworth. Nearly a century later, in January 1914, seven poets and Lord Osborne de Vere Beauclerk met in Sussex to eat roast peacock at another Sunday lunch. Six of the poets (Yeats, Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington, Sturge Moore, Frank Flint and Victor Plarr) came from London to honour the seventh, Wilfred Scawen Blunt, at his manor house. Hilaire Belloc joined them for tea afterwards, and sang a ballad about cuckoldry. Robert Bridges and John Masefield declined their invitations.

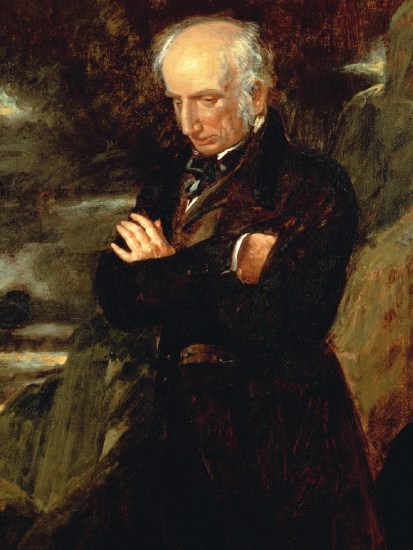

In 1817 Haydon was displaying his huge picture, ‘Christ’s Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem’, for which Keats, Lamb and Wordsworth had posed as ‘extras’. He had laboured for three years on the painting, which he would take another three years to complete. It loomed over the luncheon table in his studio, and now hangs in a seminary in suburban Cincinnati. Haydon’s copious booze excited a rowdy, cheerful dispute about the conflict between mathematical reason and artistic imagination. Keats decried Isaac Newton as a fellow who had ‘destroyed all the poetry of a rainbow by reducing it to a prism’.

Stanley Plumly, the Poet Laureate of Maryland, has used Haydon and his guests as the launch-pad for his own ruminations on the mainsprings, ambitions and insecurities of poets and painters. It is low-cholesterol fare compared with the delectable, richly buttered concoction published 14 years ago by Penelope Hughes-Hallett on the same subject with an almost identical title. Sometimes Plumly achieves a poetic precision of image, but there is an annoying archness about his use of the present and future tenses to describe past events. He makes factual errors (believing that Shelley held a peerage) and has jarring crashes of tone: a banquet given by the Prince Regent is described as a ‘high-end, royal meal’; Haydon’s daubs are said to be ‘best when he yields to real-time reality’.Worst of all is Plumly’s sententious obscurity. ‘Friendship is what we have. The families of our passions and commitments are what we share.’ Or: ‘Whatever else genius is, genius is as genius does. It is about achievement, not announcement.’

Similar infelicities spoil Lucy McDiarmid’s book, which bustles with reiterative summaries, as if she is giving brisk lectures to students with the memory span of goldfish. She tells us repeatedly, and ever indignantly, that Lady Gregory was not invited to Blunt’s ‘man’s dinner’, despite instigating it: ‘She was the link, the linchpin, the conduit, the node in the network of men.’ Like Plumly, but unlike Hughes-Hallett, she is earnest and over-analytical about the boisterous fun and provocative sallies of the two lunches.

Bathos abounds: ‘The “storm clouds of war” were not hanging over Sussex on 18 January 1914, although it was a cloudy day.’ There are inconsequential details intended to stress her familiarity with her subject, which just seem floundering. Bridges, whose wife was an evangelist of italic script, did not know, we are told, when he declined his invitation, that Blunt and Pound ‘had legible and quite pleasing handwriting’.McDiarmid is easily riled by the English class system, but gets it wrong: Sturge Moore (a Norwood doctor’s son) is described as coming from an ‘old money’ family, for example. Her glosses mislead. After quoting Blunt’s remark that when wintering in Sussex, ‘I lead the life of a tortoise’, she feels impelled to instruct her readers, ‘Tortoises are reclusive.’ They are not, but they do hibernate in winter.

McDiarmid writes with scant imaginative sympathy for men living a century ago. She has astounding confidence that the assumptions and values of the Marie Frazee-Baldassarre Professor of English at Montclair State University in New Jersey, represent some climax of human progress against which all dead white males should be judged. Her approach to history lacks tolerance or humility. She characterises, for example, the ballad that Belloc recited as ‘a mocking, lightly nasty take on adultery and male rivalry’. Like Plumly, she disapproves of the bibulous English, and especially deplores Belloc, who swilled claret while the others sipped tea. ‘The humour, such as it is,’ she sniffs at Belloc’s ballad, ‘is not immediately obvious to 21st-century readers; Belloc’s voice and performance must have added charms not apparent in the text.’

Similarly she characterises the verses entitled ‘Don Juan’s Goodnight’ that ‘wealthy, upper-class celebrity eccentric Wilfred Blunt’ recited to his guests as ‘a dirty-old-man poem’ — obnoxious ‘boy talk’ shared in circumstances of ‘homo-social intimacy’. Blunt’s guests brought him samples of their poems secreted in a small marble coffer decorated with a bas-relief (designed by Gaudier-Brzeska) showing a naked woman with a deeply incised V-shaped pubis. ‘The opening of the box’, McDiarmid suggests, was ‘analogous to the sexual act’, and its presentation at a luncheon with a ‘gendered guest-list’ necessarily ‘implicated its owner, or any male who handled it, in sexual activity’.

These two books are assiduous and assertive, but keep striking wrong notes, like a nervous guest at a dinner who tries too hard to impress. Both had a desperate need to be checked in manuscript by English readers, who could have forestalled the blunders of etiquette, nuance and fact. The parties described by Plumly and McDiarmid still sound amusing, but both authors are didactic people, whose opinions on genius, tortoises, the English class system and vaginas are not much cop.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

'The Immortal Evening', £18.99 and 'Poets and the Peacock Dinner', £20 are available from the Spectator Bookshop. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in