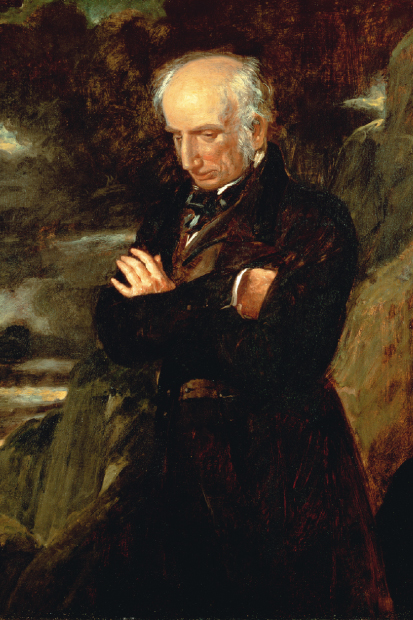

In 1960 John Steinbeck set off with his poodle Charley to drive around the United States in a truck equipped with a bed, a desk, a stove and a fridge. To renew his acquaintance with that ‘monster of a land’, he planned to cross the northern states from the east coast to the west, then drive down the Pacific and across the southern states. He was 58, and recovering from a mild stroke. Having recently abandoned his attempt to write an American Don Quixote, he called his project ‘Operation Windmills’, cast Charley as his Sancho Panza, and named his truck Rocinante. Travels with Charley was published in 1962. It was a great success, and his last major work. Four months later he won the Nobel Prize.

In 2010 Geert Mak, a Dutch journalist and historian, approximated Steinbeck’s itinerary in a rented silver Jeep. Setting off from Sag Harbor, Long Island, which when Steinbeck lived there was ‘a blue-collar place’ and is now a rich yachting resort, he was soon dismayed to learn that he was not alone: Bill Steigerwald, a journalist from Pittsburgh, was taking the same route, as were ‘a woman from the Washington Post’ and ‘someone who runs a website for dog-lovers’.

The woman from the Washington Post has left no trace that I can find. The dog-lover turns out to have been John Woestendiek, who has written Travels with Ace, a blog inaccessible to my computer. And Steigerwald of Pittsburgh has published Dogging Steinbeck, much of which may be read on the internet. He takes an ‘openly libertarian’ (i.e. stridently Republican) line against the Democrat Steinbeck, and is dismissive of his way with facts: according to him, Travels with Charley is ‘a very flawed load of fictional crap and deception’.

Mak acknowledges Steigerwald’s detective work, but is less brutal and more literary in his judgment. Steinbeck claims, for example, to have spent a night in the Badlands of North Dakota camping under the stars, listening to the barking of coyotes and the screeching of an owl, when he actually drove on to stay at an hotel. Mak concedes that ‘too many of the meetings [described in Travels with Charley] are of dubious veracity, too many facts are wrong, too many dialogues… are clearly invented’.

As a liberal European, his opinions on the current state of America are pretty much the opposite to Steigerwald’s. Where Steigerwald finds ‘few signs of real poverty’, Mak encounters ‘islands of prosperity’ amid ‘oceans of anguish and poverty’. One surmises that Steigerwald might well subscribe to the Fox News interpretation of history, while Mak certainly does not. After watching a report about how elderly people in the Netherlands are subjected to involuntary euthanasia on an industrial scale, he concludes that America’s Enlightenment quest for objectivity has been ‘replaced by hypnosis, exhibitionism and collective entertainment’.

The turning point of Steinbeck’s journey occurred at Monterey, California. He had spent much of the 1930s there, and respectable locals were outraged when he portrayed it in Cannery Row (1945) as populated by losers, drunks and whores. (Mak writes that, as an ‘ode to an aimless existence’, it is an ‘extraordinarily un-American’ novel, though the same could be said of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.) After its success the town decided to cash in, and turned itself into a sort of theme park, renaming Ocean View Avenue as Cannery Row and so on. It was this transformation that so upset Steinbeck when he revisited it, and caused him more or less to abandon his project. Monterey is the turning point of Mak’s journey, too, as he reflects that Travels with Charley is effectively the opposite of Cannery Row. The latter, based entirely on Steinbeck’s experience, was fact dressed up as fiction, while the former is best seen as a ‘road novel’.

The subtitle of Travels with Charley is ‘In Search of America’. Mak, though, puts In America ahead of ‘Travels with John Steinbeck’, indicating that for him Steinbeck is essentially a peg on which to hang a companion piece to his monumental and much praised In Europe (2007). For long sections of his narrative — his frequent historical digressions, his blizzards of statistics and his swathes of opinion — the novelist is accordingly absent. This will disappoint Steinbeck fans, but the result is not without interest or validity.

Both Roosevelt presidents figure largely in Mak’s historical analysis. He argues that the Republican ‘Teddy’ established the messianic aspect of America’s foreign policy — ‘Shall we go on conferring our civilisation upon the peoples that sit in darkness,’ asked Mark Twain in 1900, ‘or shall we give those poor things a rest?’ — and that the Democrat FDR’s New Deal continues to define the key questions of domestic politics, which concern the roles of big government and big business.

He notes that despite the extreme differences in education, income and life expectancy between, say, an American-Asian in New Jersey and a Native American in South Dakota — comparable to those between the inhabitants of a Paris suburb and rural Poland — nearly everyone hates the federal government in Washington, just as Europeans do the one in Brussels. A consequence of this is that America seems more or less to have given up on improving its infrastructure, and the nation that built the Hoover Dam is now incapable of building a railway tunnel between New York and New Jersey. If things go on this way the federal government will end up, as the economist Paul Krugman puts it, as little more than ‘an insurance company with an army’.

Steinbeck was himself a bit of a doom-monger, but he has nothing on Mak, who finds cause for lamentation everywhere he looks: the systematic corruption of Congress; the interdependence of Goldman Sachs and the US Treasury (which he compares to that between the KGB/FSB and the Kremlin); the death of the small-town heartland; the grotesque prison system; the hordes of jumbo flabsters waddling to early graves (one in three Americans weighs as much as the other two); the ‘prosperity gospel’, which sees congregations of tens of thousands praying for new cars; the way an egalitarian society is ‘turning into the kind of class-based system the Founding Fathers rebelled against’.

In America reminded me of last year’s jeremiad, George Packer’s The Unwinding. I dare say their gloom is fully justified by the facts, but there is more to the truth than facts, and I doubt if either will be read half a century from now, when Travels with Charley still will be. ‘I am happy to report,’ wrote the quixotic Steinbeck, ‘that in the war between reality and romance, reality is not the stronger.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in