Why increase

the number

of suicides?Better

to increase

the output of ink!

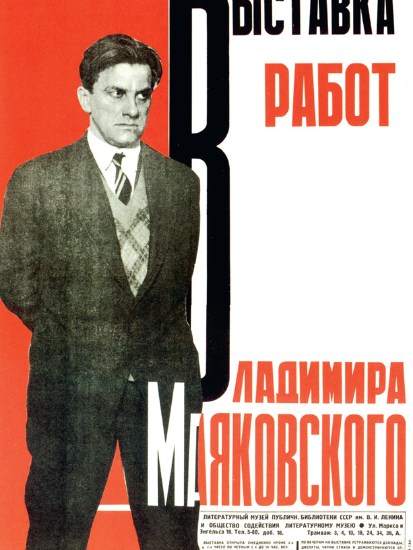

wrote Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1926 in response to the death of a fellow poet. Four years later, aged 36, he shot himself. What drove the successful author, popular with the public and recognised by officialdom, to suicide? Bengt Jangfeldt provides some clues to this question in his detailed, source-rich biography.

Mayakovsky came to poetry as a Futurist, co-authoring the 1912 manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste, which granted poets the right ‘to feel an insurmountable hatred for the language existing before their time’. That the new era demanded a new language was a principle Mayakovsky adhered to all his life. After the October Revolution he wrote poems and plays that propelled him to the top of the emergent literary hierarchy, performed for large audiences, made propaganda posters for the Russian Telegraph Agency, dabbled in film and collaborated with the Constructivist Alexander Rodchenko on innovative advertisements. In 1923, attempting to revive the Russian avant-garde, Mayakovsky launched Lef, a periodical that, despite promoting utilitarian art designed to serve the socialist state, proved useless to the ruling ideology.

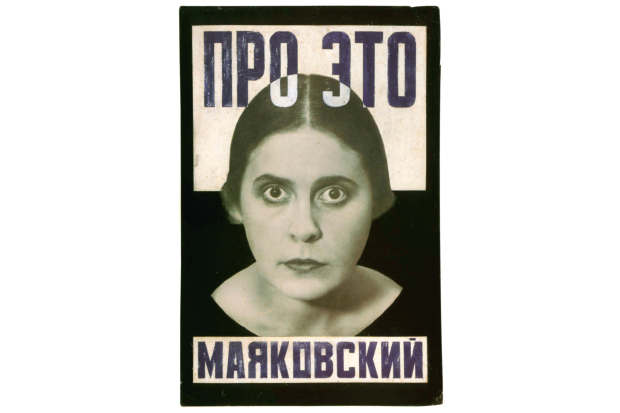

His poetry, full of neologisms, punchy metaphors, original imagery, syncopated rhythm and staccato lines, stuns the reader with its energy and self-confidence, often making it hard to discern any inner conflict. Jangfeldt portrays him as a split personality, talking about ‘the destructive battle between the lyricist and the agitator within him’, exemplified by the poems ‘A Cloud in Trousers’ and ‘About This’.

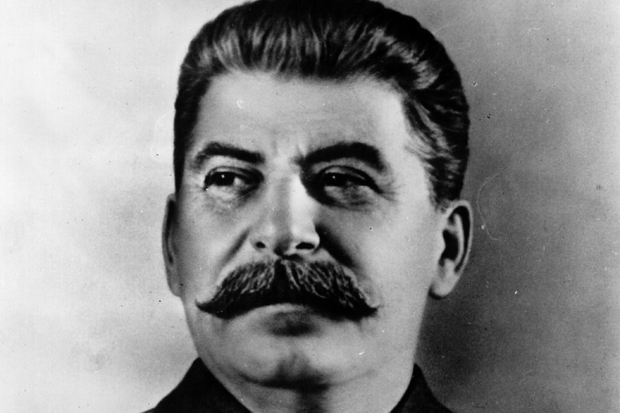

Mayakovsky’s last major work, ‘At the Top of My Voice’, a message to posterity pervaded with ‘a feeling of being at the mercy of uncomprehending contemporaries’, is dissected against the backdrop of 1929, Stalin’s ‘year of great change’. For all their insights, these critical analyses ignore the fact that Mayakovsky is incredibly difficult to translate, so the promised ‘pyrotechnic display of witticisms, word games, and brilliant rhymes’ never materialises the way it does in Herbert Marshall’s translations, published in 1965 and quoted here.

Among the book’s main themes is Mayakovsky’s private life, particularly the ménage à trois he had with Lili Brik and her husband, a relationship that left

plenty of room for extra-curricular affairs. Jangfeldt sees the charming, manipulative, fickle Lili — mentioned in the dedication along with his other interviewees — as the poet’s principal muse, while meticulously cataloguing various other relationships within their circle.

However notorious a womaniser Mayakovsky may have been, this biography tends to overdo romance at the expense of less juicy themes. In a chapter tracing the first steps of the young Futurist, the visit to Russia of the movement’s founder, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, is crammed into a couple of sentences, while the following two pages are taken up by Mayakovsky’s girlfriends and their unwanted pregnancies. In a sub-heading entitled ‘Abortion in Armavir’, about Lili’s life before Mayakovsky, ample space is similarly given to her teenage experiences. As the love motif develops, the headings grow more playful — ‘Lili + Volodya = True’;‘Changez Vos Dames!’ — sounding out of tune with the poet’s commitment to ‘roar like deep sirens vociferous’.

Jangfeldt suggests several possible reasons for Mayakovsky’s suicide: personal turmoil, the establishment’s increasingly hostile attitude, the failure of his play, problems with his vocal cords, the drifting away of his audience Another explanation, less explicit but crucial, is his inevitable disillusion with the new order, a system he could no longer identify with. ‘The word is the C-in-C of human powers,’ was Mayakovsky’s motto. For a poet who put absolute trust in language, the Soviet doublespeak that emerged a decade after the revolution must have been unbearable. ‘Freedom’, a word that rang so true in 1917, was rapidly losing its meaning under bureaucratic collectivism, a more precise term for ‘socialism’. As he watched the language of the future being reduced to hollow slogans, Mayakovsky was bound to see his own situation as a dead end.

This biography is a worthy attempt to bring Mayakovsky alive; and yet to resurrect him, we should return to his poetry, where he shouts to us across the years — ‘as the live with the living speaks’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £22 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in