My career at school and after was greatly enhanced by a series of books called The Bluffer’s Guide to….These gave mischievous advice, often on the reliable when-in-doubt-confuse-the-issue lines. A favourite of mine, still in use in emergencies, was: ‘I think Jack Kerouac was more a Franciscan Christian than Buddhist, don’t you?’

Martin Kemp’s Art in History is several clicks up the ratchet of sophistication, but, being a beginner’s guide, retains something of the character of a prop for the indolent. The curious title betrays a little uncertainty. It is one of the publisher’s ‘Ideas in Profile’ series which includes Shakespeare, Criticism and Politics. But why the preposition between ‘art’ and ‘history’? Why not just call it ‘Art’? I mean to say, they didn’t call the other titles Shakespeare in Theatre, Criticism in Literature or Politics in Government.

Perhaps this is because art historians are an insecure lot. Although Kemp, who is Emeritus Professor of History of Art at Oxford and an authority on Leonardo, is more secure than most and would perhaps disagree, art history can never quite decide what it is. The streams which fed its deep pools of sensitive experts included connoisseurship and attribution, history of ideas, Hegelian dialectic and, lately, deconstructionist palaver. It’s not really a coherent discipline at all, although, I concede, they once said that about English Literature too.

I know this because, being bad at drawing and very bad at maths, in an adolescent crisis of confusion, I abandoned architecture and defaulted to art history. As Hunter Thompson said of something else, it was like falling down an elevator shaft and landing in a pool of mermaids. My course was populated entirely by well-spoken girls headed for the art trade: it is the only humanities subject which is a good training for business. Despite the increasing presence of loopy ‘theoreticians’ in the current practice, it is a very conservative subject. One would, not, after all, wish for Christie’s assumptions about value to be questioned.

Kemp has, for whatever reason, not been tempted into any original interpretation of his subject. His explanation follows the established historical sequence of Classical, Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, Romantic, Modern and Post-Modern (although his chapters have different titles). Each begins, I think unpromisingly, with lengthy excerpts from profoundly respectable source material: Pliny, William Durandus (Bishop of Mende, since you ask), Vasari, André Felibien, Jonathan Richardson, Eugène Delacroix, Baudelaire, Marinetti and one Douglas Crimp (who may or may not be profoundly respectable; he was new to me too).

Art in History comprises very well-informed, but rather windy and prolix, accounts of familiar material, conventionally organised. I am not sure it qualifies as the ‘concise, clear and entertaining’ introduction to its subject that the publisher promises. In a book with neither footnotes nor bibliography and with thus no need to cling to peer-reviewed academic traditions, a daring profiler of ideas might have considered a more radical approach than the laundry list of style labels. What about a bit of disruption? What would Leonardo have done with the sequential nostrums of art history? And Kemp’s refusal to include a bibliography because it would be ‘unworkable’ is a bit lazy. The very difficulty of composing such a thing would have given great value to a select bibliography filtered through a fine mind.

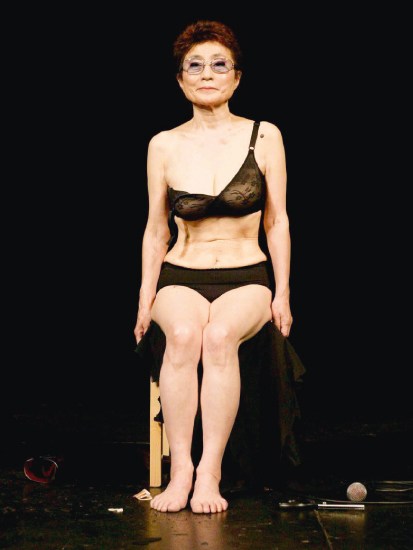

The last chapter, ‘Something Different’, where you would expect an Oxford don of mature years to be at odds with the critical relativism and preening silliness that dominate contemporary art and art history, is one of the best. Kemp is nicely testy about the preposterous Joseph Beuys, an artist who made his career out of grease and felt, and positively enthusiastic about Yoko Ono’s performance art, especially the piece where her outfit is cut down to her underwear by predatory snipping scissors. No, not Leonardo, but we move on.

I think it would be marvellous to have Martin Kemp talking over your shoulder in the Prado or the Louvre where an ad-libbed professorial commentary of great erudition would be thrillingly welcome. But it works less well in print. Alas, this book rather reads as if it were written with a gun to the head and a shrieking deadline and dismaying word-count in mind. There are coy illustrations which lack freshness or wit.

An enduring mystery of art historical culture is how little sense of style its practitioners have. Kemp writes: ‘Diderot was one of a radical group of French intellectuals determined to reform philosophy, society and culture in France.’ I mean, you could do better on Wikipedia. And instead of writing ‘painted’ he writes ‘strove to render’. Personally, I wouldn’t let a second-year student get away with either of those. Mind you, very few academic art historians are fine prose stylists. The exception was Kenneth Clark although, if you want to split well-groomed hairs, he was perhaps more of a belle-lettrist.

The art historian’s lack of aesthetic sense applies to the world too. The great Ernst Gombrich, whose incomparable Story of Art of 1950 will never be surpassed as an introduction to art-in-history, used to live in an environment of gasp-makingly artless clutter — borderline squalor. But Gombrich gave us the fine apothegm: ‘There is no such thing as art. There are only artists.’ Martin Kemp gets nowhere near such synoptic genius. I don’t think he even tried. Gombrich is now in its 16th edition. I doubt that Kemp, in this version, will get that far.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £8.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in