In the centre of the new exhibition Sculpture Victorious at Tate Britain there is a huge white elephant. The beast is not, I should add, entirely colourless. On the contrary, it has a howdah richly decorated in gold and green, and numerous trappings, and tassels covering its pale grey hide. Its whiteness is entirely proverbial. After all, what can you do with a porcelain pachyderm, standing over seven feet tall?

The Victorian period, a text on the wall proclaims, was ‘a golden age for British sculpture’. This is perfectly true, in the sense that a colossal amount of the stuff was turned out during Victoria’s reign. But, as the exhibition unintentionally demonstrates, there was a lack of clarity about what to sculpt, with the exception of the monarch herself (numerous statues of whom were distributed around Britain and the Empire).

Sculpture Victorious is like a 19th-century department store, containing little in the way of major art, but cluttered with entertainingly barmy objects. My favourite, for its almost surreal dottiness, is ‘A Royal Game’ (1906–11) by William Reynolds-Stephens: a massive representation in electro-typed bronze of Philip II of Spain and Elizabeth I, playing chess but using models of Armada-era ships instead of the conventional rooks and pawns. The artist intended this as ‘a suggestion for a new form of National Monument’.

It turns out the elephant was one of a pair, modelled by Thomas Longmore and John Hénk and made by Minton & Co to display at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889. In other words, it was a bit of advertising. Or, as the catalogue more grandly puts it, Minton’s elephants were ‘the standard bearers of British artistic skill and industrial might in this intense international competition’. One hopes the French were impressed; although the Minton elephants faced formidable rivals for attention in the freshly completed Eiffel Tower and, among the other sculptures on view, Rodin’s ‘Kiss’.

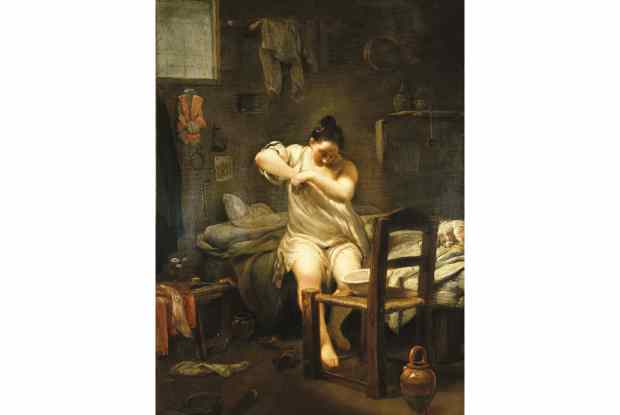

Stylistically, Victorian sculptors veered between implausible evocations of the Middle Ages and pastiches of classical antiquity. ‘Greek Slave’ (1844) by the American Hiram Powers is a weak imitation of classical nudes stretching back to the Venuses of Praxiteles, made in the traditional medium of marble but with a contemporary political spin. This was not supposed to be a goddess, but a modern Greek woman who had been captured in the recent War of Independence and displayed naked and in chains in an Ottoman slave market.

‘Greek Slave’ was a hugely successful work, but it’s not the vapid object itself that catches your eye, but the numerous images of it that circulated in porcelain, engraving and various types of photography. If the Victorians were not much good at sculpture, they were brilliant at finding novel means of reproducing and manufacturing it.

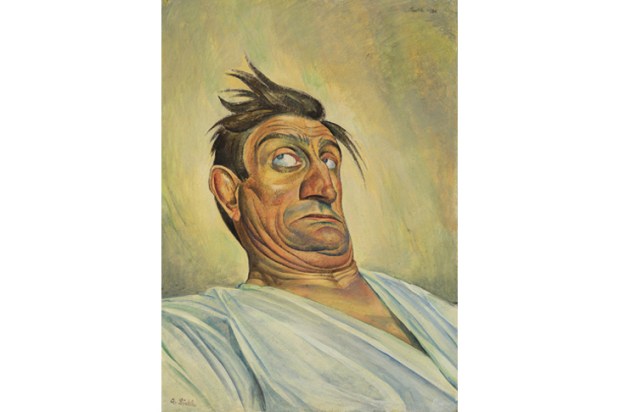

The first work on show, a bust of the young Victoria from 1840 by Sir Francis Chantrey, is a case in point. Though he died in 1841, two years after the advent of photography, Chantrey devised a highly successful, pre-photographic, quasi-industrial way of making sculpture portraits.

Chantrey ran a sort of sculptural production line. First, he in person made a drawing using an optical device called a camera lucida, essentially a prism by means of which the image of the sitter was superimposed on the drawing paper where it could be traced. This was transformed into a clay model, then a plaster one, and finally carved in marble by specialist craftsmen.

The finest exhibit in Sculpture Victorious is also a bust of Victoria (1887–9) by Alfred Gilbert (the nearest thing to a genius among 19th-century British sculptors). And this, too, is a photographic sculpture — or at least one apparently based, in its sharp textural detail, on photographs.

Photography was the most sensational visual innovation of the age and like many major inventions it was discovered, independently and more or less simultaneously, by a number of people. First to go public was a French artist, Louis Daguerre, in 1839. Batting for England was William Henry Fox Talbot MP of Lacock Abbey, Wiltshire, who devised a method of making images using sheets of paper coated with silver salts.

Salt and Silver displays some early examples of the technique. It is a complimentary exhibition to Sculpture Victorious: a quiet monochrome experience in contrast to the Lewis Carroll fantasia of the other. Over the past century and a half, it demonstrates, photography has not progressed from the aesthetic point of view.

Some of the earliest photographs ever taken, by Talbot himself and the team of David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson in Edinburgh, are the best. Perhaps they gain added poignancy from the sense that we are seeing our ancestors emerging into the gaze of the modern world, like some hitherto-unknown Amazonian tribe, their images fixed by a lens for the very first time.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in