The album is not what it was. It still exists, in record collections, as part of the torrential streaming of everything, and in the sentimental memories of those who lament the loss of what once seemed a permanent fixture and the most exciting, unimpeachably authentic way of capturing and keeping music. Many musicians refuse to relinquish the idea — length, number of songs, conceptual framework, illusory two sides, solidity, sound — of the album. It remains worth hearing what a musician like PJ Harvey might have to say about the album, because it is where she has worked for 20 years, and so she has built up enough momentum to make her next one intriguing. She’s one of the last rock artists where this is truly the case. Even she is still working out how to give the album, as developed in the late Fifties and early Sixties, a significant afterlife, relevant to anyone outside a shrinking set of conservers and preservers.

Her current solution is to conceive ‘the album’ as a series of performance art pieces set inside an installation version of the all but extinct recording studio. Recording in Progress sets her inside a glass box in a fresh white underground room at Somerset House, chosen for its acoustic and historic properties, while she works for a few weeks, to a strict schedule, on her ninth album. The enforced discipline produces results; an album is quickly made, sounding — somewhere between naturally and self-consciously — just like the latest PJ Harvey album.

Every so often 40 or so visitors who managed to get a ticket stare through the one-way glass at what she’s up to with her musicians, engineers and producer. (It’s luck whether you get your allotted time — about 45 minutes — filled with random tuning up or a repeated cymbal sound, or a full-blooded performance of a near-finished song with actual action from Polly.) It’s as much a PR event as a mutating living sculpture — as it is grandly set up. A little bit theatre, a little bit celebrity-spotting, it’s a novel, exclusive way of hanging out and showing off, and perfect for those who think that creativity can be explained, like growing veg and sewing hems.

Surrounded by many middle-aged male musicians who look like the type who cherish the album, Polly efficiently pretends to be oblivious to those politely staring at her like a specimen in a zoo. Whatever else the album seems to be about, the story is really that they recorded it in this box, under self-imposed pressure, while random visitors looked on.

The idea, then, is not really about generously sharing rare insight into the mystery of recording. It’s about protecting the threatened notion of the artist with a singular irreplaceable vision. The shape, the meaning, of this album, is front-loaded to compensate for the fact that when it is released it will be a shadow of an album, a ghost, a relic, mostly downloaded and streamed. It will flow off into the foam of everything else, like most things do now, struggling to establish enduring, distinctive value.

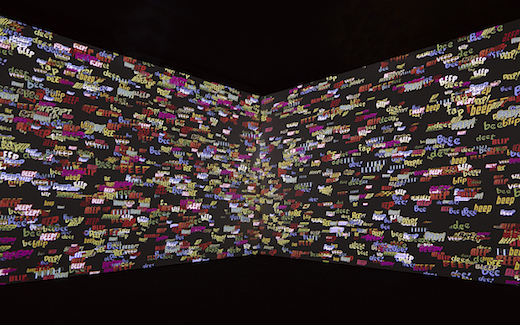

At the White Cube in Bermondsey, as part of the Christian Marclay exhibition, neatly fusing sound, image, process and silence, there is more white-walled, art-infused reverence for the crumbling glory of the album, and a solemn celebration of the 16 or 17 minutes of music you could fit on to one side of a record. Over a few weeks, amid delightful light shows, visualised sound and sonic reminiscences, Marclay is performing and commissioning in various settings various musicians from classical, rock and improv. Christian looks back not to conventional rock and blues, but to experimentalism, turntablism, krautrock and noise, to Cagian chance, Feldman deliberation and Fluxus play. He reanimates various marginal, once almost-extinct pursuits that are better presented in a museum or gallery setting as happenings, collaborations, inquests and occasions rather than as formal concerts.

An avant-garde superstar electric guitarist participates — Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore — but he carefully takes part in proceedings merely as one of the signals flowing through, priestly and diffident, not as distracting glamour. He draws a bigger crowd than some in the series, but then the biggest draw is that the shows are free. It costs £25 if you want a record of the event, pressed in the gallery as part of the exhibition, turned into something that resembles a homemade punk record. You can watch the manufacturing process, the records being fashioned on an impressive-looking industrial machine intended to elevate the romance of vinyl, but confirming that it’s frail and doomed and from another time, like the telephone box.

It might be that the time has come for the album to be moved into the museum for a slow, dignified — or not — drift into history. Or it might be that the album was not the culmination of something, but the roots of something else. There’s a suggestion at the White Cube, the art gallery transformed into free-spirited music venue, and inside Polly’s insulating glass box, of a new form emerging. It’s the album’s response to the brutal digital world. The listener compiles their own experience and constructs the running order and the artwork from pieces scattered across a number of dimensions, as installations, experiences, events, images, one-off pieces, TV channels, websites, publicity campaigns and overheard moments. The old single solid object containing songs and performance is replaced by a non-linear mixture of objects, communications and sounds. If you can’t bear that thought, you’d better yet again rearrange your stuck-in-time record collection and stick your fingers in your ears.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in