I’m not sure I know what the mark of merit is in a first novel, any more than in a fourth or a 14th. If nothing else, though, it’s surely an opportunity to make a new friend, to lock eyes with a stranger across a crowded room. So it was, one enchanted evening in February, that I carted a hodload of literary debuts across the threshold. Somewhere within, I hoped, was the beginning of a beautiful lexical relationship, or possibly several.

Four weeks later, I’m not so sure. For one thing, most of the books were baroquely overpackaged and strenuously oversold. Publishers may have sound commercial reasons for pretending that first novels aren’t first novels — we know it’s a nervous time for the trade — but it seems cowardly of them: if we like reading, why wouldn’t we want to read something new?

Instead, more or less without exception, you get a quote from an established author on the front, a jacket design that looks markedly, sometimes actionably similar to an existing book, a blurb that strives to locate the book in some already existing microgenre or other (Family secrets! Religion! History! Nature!). Indeed the impulse to surprise seems to have been transferred entirely to the author biography, so we are breathily told that A lives among vineyards, B is a champion skateboarder and C has two science degrees but loves literature (why ‘but’?).

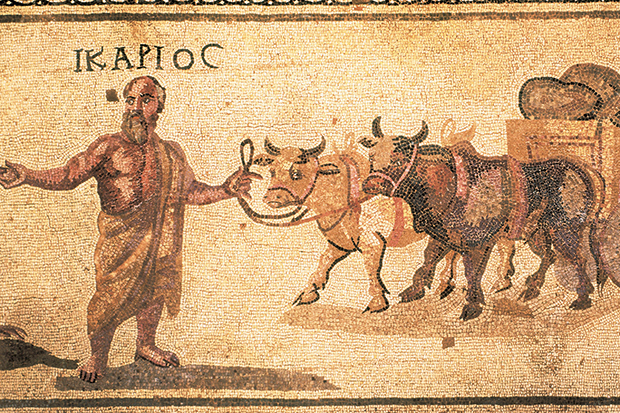

Nevertheless, I shall be asking for a second date with a few of these books. The Scapegoat by Sophia Nikolaidou (Melville House, £18.99, pp. 320, Spectator Bookshop, £16.99) knits multiple voices and perspectives together into a sort of thriller that is also an examination of modern Greek political history — useful background reading for these interesting times. The process of translation (here by Karen Emmerich) brings a cool, affectless quality to the prose.

One Night, Markovitch by Ayelet Gundar-Goshen (Pushkin Press, £10, pp. 384) is a funny, energetic, voluptuous love story set in Mandate Palestine. There’s a strong whiff of manifest destiny about it — Palestinians are decidedly thin on the ground — and at times one is tempted to put in a call to the magic realism police (genitalia taste of citrus fruit in a way that may not tally with many readers’ experiences). But page by page, the most exhilarating writing of the pack was to be found here.

Two very different books both consider the difficult outer areas of the parent-child bond. If I Fall, If I Die by Michael Christie (he’s the skateboarding one), published by Heinemann (£12.99, pp. 336, Spectator Bookshop, £10.99), tells the story of Will, a pre-teenaged boy, and his gradual escape from the suffocating love of his depressed, agoraphobic mother. It shares a few strands of DNA with both Emma Donohue’s Room and Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time — only where those books have a faint whiff of modernist experiment about them, exploring what happens to a character or a narrative when you drain language or possibility from it, Will’s world is over-full, padded and inflated: his paintings are ‘masterpieces’, the rooms of the house he hardly ever leaves are named after great cities of the world.

The book is flawed, to be sure: it is, as critics always say of first novels, overwritten; the redemptive mechanism (guess what: it’s skateboarding) will not engage or convince anyone who’s not already disposed to buy it; the finale is trite. Yet there are moments of real tenderness, and real strangeness too, as Will gradually embraces risk and seeks friendship. It feels less part of some sub-genre cooked up by the marketing department than a contribution to a real, archetypal literary tradition, that of the coming-of-age story.

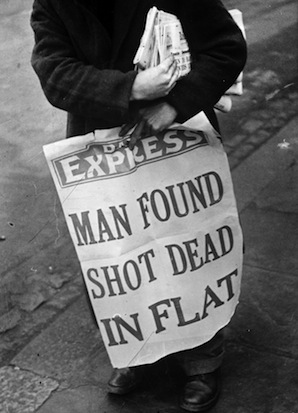

In The Glorious Heresies by Lisa McInerney (John Murray, £16.99, pp. 384, Spectator Bookshop, £13.99), coming of age is an uncertain prospect for Ryan, the nearest thing we get to a juvenile lead. The book is a rambling, picaresque ensemble piece set in Cork, a suitable location for such a tale if ever there was one, with a thriving criminal subculture, and a generous stock of decaying waterfront buildings. At, or orbiting, the heart of the matter are Maureen Phelan, disgraced single mother, arsonist, accidental mob matriarch; her prodigally destructive son Jimmy, gang boss of all he surveys; Jimmy’s old friend turned stooge Tony, the limp father of half a dozen; meddlesome Tara next door, a veritable superconductor of covert information, and a sexual time-bomb whose tick has grown fainter with the years; and Ryan, Tony’s eldest, whose bright future gradually dims as we turn the pages.

This too, is by no means a book without fault — though its purple patches ring more true, all the characters having apparently some intimate knowledge of the Blarney stone. It’s melodramatic, and far from cliché-free. But it’s the one I reached for as my book at bedtime, the one I tore through most hungrily. Partly, it’s the setting: I know Cork a bit and it’s a town with a particular, doleful character (Joyce’s father, the model for Simon Dedalus, was a Corkman). The acrid tang of second-city blues in the air suits the bathetic aspects of the story, its vectors of failure and fate, while furnishing an environment in which its more Gothic elements can credibly unfold. But the strongest thing about the book is its security of characterisation and tightness of plot; and particularly, the way in which turns of plot are tangibly shaped by the flaws that even the more likeable characters (and they’re all likeable to some extent) possess.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in