A few months ago I went to a lunch at Univ, my old college in Oxford, to celebrate the 95th birthday of my Ancient History tutor George Cawkwell. There were toasts and speeches, including one from George himself and my fellow student Robin (now Lord) Butler, who did a brilliant imitation of George getting all excited when describing the battle of Marathon and reverting, temporarily, to his native New Zealand accent.

In the company of such men, not forgetting another fine speechmaker, Edward Enfield, also one of George’s pupils, I felt ill at ease. There they were, overflowing with classical allusions, and there was I, wondering how I could have forgotten almost everything I had known about the ancient world including the battle of Marathon. Yet from the age of seven, when I first started learning Latin, up until my 24th year when I left Oxford, allowing for a two-year gap for National Service, I had done almost nothing but study Latin and Greek. And now I could remember scarcely anything about either of them. Show me a piece of Latin prose and it is all Greek to me.

The Ancient Art of Growing Old by Tom Payne, who teaches classics at Sherborne, helps me to understand, to some extent, how and why I have let George Cawkwell down. It is a scholarly but reasonably light-hearted essay about the classical view of old age — ancients on oldies, in other words. Not surprisingly, there is a heavy emphasis on Cicero, who wrote a short book — De Senectute — on the subject. It is hard to overemphasise the effect that the mere mention of Cicero can have on a man who as a schoolboy had to sweat blood translating his speeches into English, usually with the help of a (forbidden) crib. I know that Cicero is as much a hero to my friend Robert Harris as Thomas Cromwell is to Hilary Mantel, but I doubt if Harris ever had to grapple with Cicero in the original; even in the crib he comes over as a humourless and self-satisfied bore when he writes that ‘the fruit of old age is the remembering and amassing of fine accomplishments’. Contrast the sentiments of a finer and humbler man, Samuel Johnson: ‘When I survey my past life, I discover nothing but a barren waste of time with some disorders of body and disturbances of the mind very near to madness.’

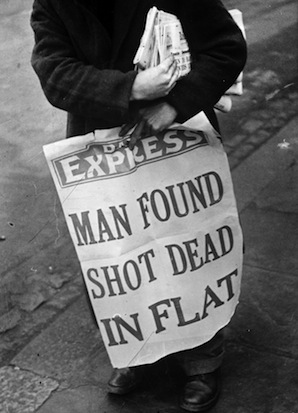

Not only was he smug and over-pleased with himself: Cicero, I learn from Payne’s book, was sufficiently concerned about his posthumous reputation to write to one Lucceius, who was working on a history of the times, brazenly asking for a better write-up in the book than he deserved: ‘I ask you outright again and again’ (poor Lucceius was obviously being regularly pestered by Cicero) ‘both to praise those actions of mine in warmer terms than you perhaps feel and in that respect to neglect the laws of history. I ask you too… to yield to your affection for me a little more than truth shall justify.’

Perhaps we ought not to be too shocked by Cicero’s invitation to Lucceius to doctor the facts. He was, after all, a lawyer well-practised in the art of making the best case for his client, even to the extent of twisting the truth.

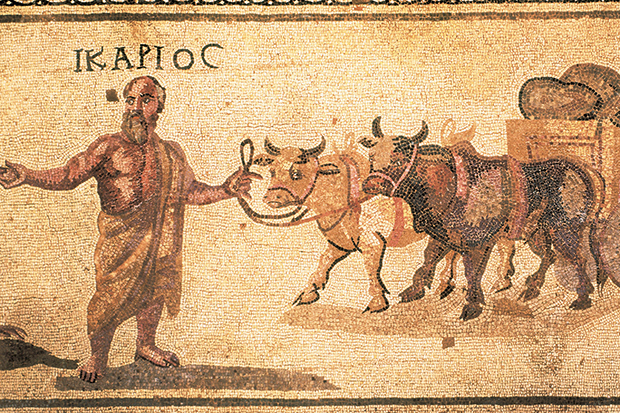

Payne devotes a large part of his shortish book to a translation of De Senectute, which is written in dialogue form, like many of Cicero’s philosophical works. Besides being unduly platitudinous, it makes generally for unhappy reading. When it comes to offering tips for those growing old, apart from sitting on the sofa thinking smugly about all your great achievements, Cicero recommends taking up agriculture.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £12.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in