To the extent that Britain has philosophers, we do not expect them to address issues of any relevance to the rest of us. They may pursue some hermeneutic byway perhaps, but not the urgent or profound issues of our time.

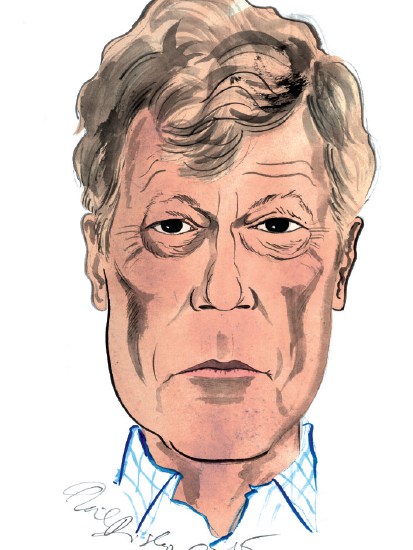

Roger Scruton has always been an exception in this regard, as in many others. He has spent his adult life thinking and writing about the nature of love, the nation state, belonging, alienation, beauty, home and England. But even his closest readers may gulp at the relevance of his latest subject matter. His new novel, The Disappeared, is set in the north of England and centres on the recent rape-gang cases. It’s a gripping, disturbing narrative dealing with abduction and abuse but also love, escape and a type of redemption. I went to see him last week, a world away from all these subjects, at his farm in Wiltshire.

‘I’ve been thinking about these things for quite some time,’ he says as we settle into his book- and piano-filled study. ‘The problem of the integration of the Muslim community into our cities.’ He is aware of the landmines on this territory. Thirty years ago he inadvertently stepped on one by publishing a piece by a Bradford headmaster, Ray Honeyford, about multiculturalism in schools. ‘I looked back at my experience [in 1984] with the Salisbury Review and the Ray Honeyford case and the huge difficulty that teachers have. Because our political class has transferred to teachers the whole obligation to integrate new immigrant communities… People find themselves with classrooms where nobody can speak English, with customs they can’t relate to and with those problems that Honeyford had with discipline and outright antagonism. That was in Bradford, and of course when I read about the Oxford grooming cases, I just had this vision of a story that would bring these things together — the dreadful situation of the teacher in a modern city, and also the situation of young girls who are vulnerable because their families have not worked out and the various problems that have arisen through secularisation and so on. And so I put together a story out of these things.’

Readers of his columns and works of philosophy may wonder why he chose to tackle this through the medium of the novel. ‘I’ve always taken the view that works of art are not just things that we enjoy. They can convey truths about the world more vividly and to greater effect than ordinary philosophical prose can because they don’t just deal in ideas but show the emotional reality of them. And I think that our society has gone terribly wrong because people have not been confronting the great issues — the loss of the Christian faith, the inability to confront Islam, the loss of the sense of the sacredness of the sexual relation, and the exposure in particular of young women both to external predation and to this moral decay. All these things are real. In my book the principal teacher is someone who is also attracted to the girl victim and that raises another big question — the question of paedophilia, which has a huge hysteria about it in this country because it is the last remaining redoubt of innocence, of childhood, but it’s also the thing that everybody for that reason is assaulting.’ Why assaulting?

‘Well, because innocence and purity are objects of sexual desire. In a healthy society, this desire is maintained, while also maintaining the wall which protects innocence. But that wall has crumbled, which is why there is this sort of public hysteria about paedophilia. It’s the last remaining crime in the sexual area. Putting all these things together just enabled me in a story, in a novel, to connect emotionally, not just intellectually.’

This desire to communicate — to connect — runs throughout all of Scruton’s work but seems to have grown with the years. He has started a family, and discovered a great love of hunting fairly late in life. But as the remaining sun of an English spring day filters across the study, there is also an ever-present sadness. Something like a permanent bruised-ness. The Honeyford affair helped destroy Scruton’s career in the universities and he knows why so few people address these issues.

‘The truth is hard. We don’t need reminding that there is a heavy censorship in all matters to do with immigration, to do with the integration of immigrant communities and in particular the integration of Muslim communities. The police forces of those northern cities were heavily intimidated by the Macpherson report, accusing police forces all over the country of institutional racism, which was an incredible injustice, which means they are going to lean over backwards not to get involved in what’s going on in the local immigrant communities for fear of this. That’s clearly what has happened in Rotherham and also people don’t want to write about it because they’ve also seen the penalties.’

He has been hearing the same stories from teachers for 30 years now. ‘If you’re a schoolteacher and trying to survive in these circumstances and knowing that you’re up against all these assembled forces, then self-censorship is not just likely, it’s necessary. But if you’re a philosopher who is self-employed at the end of his career, then it’s pointless to engage in self-censorship. It’s great, I can just say what is true. People will shout and scream, and all the usual things will be said. But more and more people will realise that this self-censorship is not just counter-productive in itself but has actually worsened the problem because it has prevented people from dealing with it. It has prevented the immigrant communities themselves from dealing with it.’

But things have got better, haven’t they? Hasn’t the discussion at least opened out? We are speaking a couple of days after Trevor Phillips has made another noted intervention, attacking those ‘anti-racists’ who have shut down debate for years. This prompts a classically Scrutonian response: ‘Things have changed now because as always when a battle is lost you can speak freely about it.’

Does he really mean that? I ask with trepidation. ‘The big battle to maintain a proper educational system which will be continuous with the old curriculum and passing on what we have while adapting to all the changes, that big battle was lost, I think.’ When? ‘Over the past 20 years. Certainly by the time that New Labour were in they didn’t have much work to do. When people first raised the question about integrating the new communities it was in a spirit of hope — that one would be able to maintain the core of what we have. It’s the other side who actually want to destroy that core. Certainly the multicultural activists in the Labour party and the universities wanted to destroy the old white Anglo-Saxon education system as they saw it, and produce something completely different — with no conception of what that completely different thing would be, of course. It’s always easier to destroy than to create, and I think that’s what we’ve seen. But then people start again.’

What are the signs of rebirth? ‘I was very impressed visiting Katharine Birbalsingh’s free school the other day — 110 faces, all of them black except for a little handful of Romanians — in which there was real discipline and they were being taught the old curriculum and the teachers were really trying to integrate these children into what they saw as the culture to which they were destined.’

So the battle is for continuity? ‘Yes, and for the survival of western civilisation. It’s not as though we’ve lost it completely. We still have got this civilisation — it’s all we’ve got, and it’s not as though we’re going to be able to replace it with any other. I think that’s really what underlies this story of The Disappeared. A lot of things have disappeared.’

Having been made something of a pariah for recognising these truths early, does he feel any sense of vindication? He laughs slightly. ‘I don’t feel as though I need it. It’s the way the world is. If you say something in advance — if you describe a problem as it arises, people always turn on you because they don’t want to hear about it. But when it’s too late to do anything, they will then turn around and say that you were right. That’s human nature.’

Despite being fêted and honoured across eastern Europe for his work with dissidents behind the Iron Curtain, and despite his worldwide renown as a philosopher, Scruton is still without honour in his own land. Does this upset him? ‘We live in a time when honours and praise go only to people on the left, essentially because they seem harmless. And what makes them seem harmless is precisely that they’re uttering all the things that have caused so much harm.’ Only one honour really got to him. ‘Nothing upset me more than the award of Companion of Honour to Eric Hobsbawm in reward for a lifetime of unswerving loyalty to the Soviet Union.’

But Scruton is not a regret-filled man. He seems content, even happy, in his ‘Scrutopia’. As we wrap up his wife is bringing their son home with some schoolfriends. The horses and cows need checking, and the chickens need to go down for the night. ‘Touching creatures,’ he notes as they follow him to their home, clucking and chirruping.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in