This week, some 200 years since Goya’s ‘The Disasters of War’, almost 80 years after Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, and over 50 since Malcolm Browne won a Pulitzer for his photograph of a self-immolating Buddhist monk, the British media found itself questioning whether art should, or even could, ever represent the horrors of recent history. It was a conversation that picked minutely over the ethical responsibilities of an opera based on the events of 9/11 — was it too soon? how would the families feel? would it exploit tragedy for drama? — but one whose ceaseless moral whys and wherefores prevented it ever arriving at the only real artistic question: how?

The answer is only partially provided by Tansy Davies’s debut opera Between Worlds, commissioned and staged by ENO at the Barbican Theatre. Correctly predicting the tide of public discussion and opinion, Davies, librettist Nick Drake and director Deborah Warner have created a work that is so determined to be respectful, so careful not to make the wrong sort of statement, that it risks saying nothing at all. The result is a musical act of mourning, of meditation — strikingly lovely at times, at others poignant — a Passion perhaps, but not an opera.

9/11 was perhaps the first truly self-reflexive tragedy — the first epoch-making event to watch itself playing out on television, to textualise itself even as it happened. According to Drake, ‘half a million messages’ were sent in the 102 minutes between the first plane hitting and the second tower falling — everything from personal emails to police communications. Where once an artist’s role was to preserve experiences that might otherwise be lost, now it is to translate experiences already preserved into something else, something more truthful than the truth itself.

This is where Between Worlds loses its way. Drake’s libretto draws on what he calls the ‘DNA’ of verbatim accounts, without actual quotation. But where the simplicity, the banality, of first-person speech can devastate, the manufactured simplicity of art here feels mawkish, reductive. Often inaudible, lost without surtitles in the glittering scuttlings and rustlings of Davies’ score, Drake’s text anchors Between Worlds to the literal, even as Davies’ music reaches towards that metaphorical freedom that so chills in Richard Drew’s iconic 9/11 image ‘The Falling Man’. The idea, oft-repeated in the various programme notes, that music reaches beyond words to places other arts can’t access, forgets opera’s co-dependent relationship with text. Interestingly it’s when Between Worlds collapses into wordlessness, in orchestral interludes (efficiently conducted by Gerry Cornelius), or the convulsive vocal percussion of the Shaman (countertenor Andrew Watts), that it speaks most vividly.

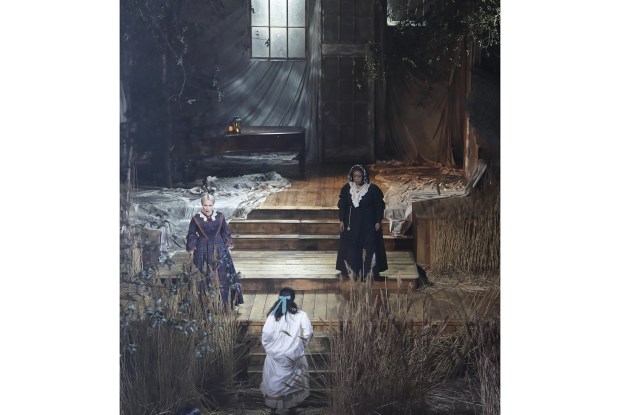

In order to tackle so monumental a subject, Davies makes the only choice possible and tells the story of a handful of individuals. We follow them from the domestic beginnings of their days — partings with children, spouses, partners — to their business meeting on one of the upper floors of the North Tower, where they remain trapped until its eventual collapse. But it’s a close-up approach not supported either by Drake’s text (which turns characters into archetypes, identified only as Janitor, Younger Woman, Realtor) or Michael Levine’s widescreen set, which uses video projections and a multi-storey structure to give a sense of scope and scale to the action. The addition of the business-suited Shaman figure — a ‘spirit guide’ for the humans he watches over below — confuses matters further, spreading the balm of mysticism on a social wound that simply cannot be staunched.

Warner’s direction is tidy and tasteful, her visual gestures so understated that one of the characters has to explain the collapse of the South Tower. But the symbolism feels lazy; we’ve seen those falling clouds of papers too often for them to capture the terror, the horror, the specificity of this event. Without first passing through the smoke, the heat, the dust and the desperation we cannot earn the consolation of the closing Requiem lament, so beautifully sung by Susan Bickley (Mother) and the ENO chorus.

Davies’s score is structurally ambitious — a real arrival for this British composer. If the vocal lines never quite match the interest of the orchestral writing, never blooming out of functional arioso into the arias that give John Adams’s operas their emotional flashpoints, Davies compensates with a multiplicity of instrumental colours. She goes one better than Adams, however, whose Doctor Atomic abandons music in favour of sound at the critical moment of explosion, creating a blunt, traumatic moment of orchestral impact, as alien as any of the ‘found sounds’ she uses elsewhere in her music.

History, according to Auden, ‘may say Alas but cannot help or pardon’. Art’s function is to fill those gaps, to go beyond grieving, to say more than ‘Alas’ when faced with events of such horror. Between Worlds is a dignified and respectful tribute, one that left much of its audience visibly moved on opening night. I wonder, though, how many were stirred by the opera and how many by the events themselves, whose tremors we still feel so strongly 14 years on.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

![A woman-child of dangerous assurance: Allison Cook as Salome in Adena Jacobs’s new production for English National Opera. [Catherine Ashmore]](https://www.spectator.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/6Octopera.jpg?w=620)

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in