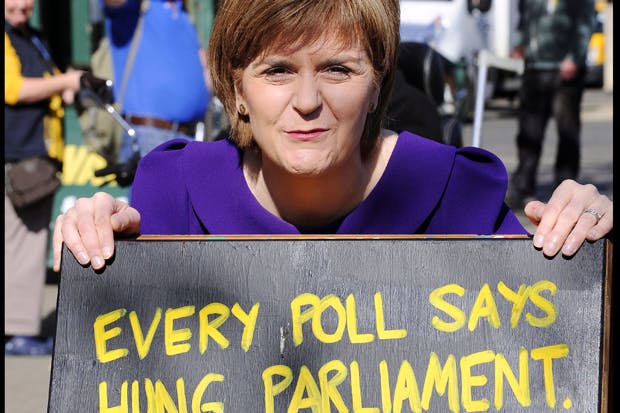

The election campaign is becoming increasingly dominated by a small party whose raison d’être is to preach independence from membership of a union it claims is hindering national ambition. But the party is not Ukip, which had been expected to play a big role in this election. It is the Scottish National Party, which seems ever more likely to hold the balance of power after 7 May and is determined to use it ruthlessly to its own advantage and to the furtherance of its sole objective: the dissolution of the United Kingdom.

Nicola Sturgeon has been the only party leader talking about the virtues of national self-government, and she has met with reasonable success. No one else seems to be trying it. Nigel Farage is fighting the campaign as if it were a by-election in South Thanet. The EU has scarcely been mentioned by his rivals — along with all other issues that relate to the outside world. The orthodoxy is that voters are, in effect, stupid and can only handle one word at a time. Labour wants that word to be ‘fairness’; the Tories want it to be ‘stability’. Those seeking a wider, more substantive debate will have to wait until the election is over.

It is hardly as if the issue of an in-out referendum has been neutralised. David Cameron, in committing himself to such a poll, seemed to be in a strong position over Ed Miliband, who has declined all pressure to follow suit. Cameron can justifiably say to anti-Europeans that a vote for him is the only way to ensure that the country has a chance to reject EU membership. For EU supporters, he is offering the chance to settle the matter of Britain’s membership for a generation to come. And for sceptics in the middle who want to be part of the EU, but a reformed one, he is promising renegotiation of Britain’s terms.

Ed Miliband’s position, by contrast, is simply one of denying the people a say on an issue which divides the country — on the basis that voters cannot be trusted with such questions. It is entirely believable, should Labour come to some sort of pact with the SNP after the election, that we will end up having two referendums on the subject of Scottish independence, with the EU question remaining unresolved. Even the pro-EU Greens want an in-out referendum on the — for them, unusually solid — grounds that the issue of Britain’s membership will be an issue until it is seen to have renewed democratic legitimacy.

Ironically, Europe would have been more in the news had there been no general election campaign. A casual observer of the headlines over the past three weeks could be forgiven for concluding that Greece’s economic problems had been solved — or at least that the matter was under control and negotiations with the ECB going well. In fact, Greece has never been nearer the door to an ignominious exit from the euro, and is on the point of defaulting even on its IMF loan, due to be repaid on 12 May. The Syriza government, now well past its honeymoon period, is rapidly losing its powers of persuasion.

The British jobs miracle continues, but under EU rules it has become our most powerful tool of foreign aid. Mr Cameron is right to boast about the two million extra jobs he has created (see page 10), but he doesn’t say that half of this rise in employment is accounted for by immigration. To paraphrase Dr Johnson, the noblest prospect an unemployed Spaniard now sees is the easyJet to London. Cameron now pledges another two million jobs, which implies (under the EU’s freedom of movement) another million immigrants. They’ll need houses, schools and hospitals. We can welcome them, by all means, but let’s be honest about what must be done to accommodate them.

David Cameron ought to be turning European turmoil to his electoral advantage. With Ukip at around 13 per cent, he would win a strong Conservative majority if only he could persuade a quarter of Ukip’s potential voters over to his side. Contrary to talk about the left being in advance, the conservative parties (the Tories plus Ukip) between them are registering a substantially bigger slice of the vote than in 2010.

Conservative strategists like to compare this year’s election with that of 1992, when John Major appeared to be in deadlock with Neil Kinnock in the polls, and yet went on to win a 21-seat majority (as Bruce Anderson recalls on page 12). They are partly right: this election is like 1992, but they have the wrong one in mind. It is more like the US presidential election of that year when an independent conservative candidate, Ross Perot, took enough votes away from George H.W. Bush to hand Bill Clinton victory.

A decade ago, David Cameron turned around a leadership election he appeared to be losing by making a brave speech at the Conservative conference. He has never been in greater need of a game-changing moment. He has made the bold and necessary decision to promise a referendum on EU membership, which itself demonstrates a substantial vote of faith in the public. A faith that Ed Miliband simply does not share. Europe deserves to be an issue in this campaign — and the Prime Minister quickly needs to make it one.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in