Every time I sit down to a Noah Baumbach film I think I’m going to hate it, but I never actually do. From the French New Wave idiosyncrasies of 2013’s Frances Ha to the growing pains of his semi-autobiographical breakthrough The Squid and the Whale, Baumbach always manages to stay just the right side of pretentious, creating lively hipster-filled worlds that amuse as much as they annoy.

Nowhere is this delicate balance more on display than in While We’re Young, a heartbreaking and cautiously funny swipe both at unwelcome middle age and the follies of youth. For Josh (Ben Stiller) and Cornelia (Naomi Watts), the childlessness of their forties has hit them somewhat unexpectedly. Suddenly the well-meant but overbearing concern of two friends who have recently become parents pushes them to look for new experiences beyond the confines of their middle-aged world (never has a baby music class filled them — or me — with such terror) and they start hanging out with two liberated twenty-somethings, Jamie (Adam Driver) and Darby (Amanda Seyfried), who reignite their creative passions, encourage them to wear fedoras and invite them to pseudo-spiritual hallucinogenic gatherings. This Is 40, Baumbach could have called the film, if Judd Apatow hadn’t already taken that title.

Jamie, like Josh, is a film-maker and, to begin with at least, his professional admiration and hunger for guidance fills Josh with a sense of accomplishment he has long felt missing from his own career, where he has been making the same documentary for nearly a decade after a single hit film in his youth. But the youngster’s esteem also makes him question everything he has achieved thus far — or hasn’t. Is his career going anywhere? Has his marriage become dull? And, most pressingly of all, are he and Cornelia drawn to youth because they are unwilling to grow up? Can they really be a success without children?

One might argue that the film’s ultimate response to that final question is its one great failing, as it draws to a marginally disappointing close. But really that’s small potatoes in a film that somehow manages to laugh both at and with Brooklyn beatniks at the same time — no small feat — and which offers the perspectives of forty-somethings and twenty-somethings in equal measure.

As the friendships begin inevitably to fall apart, no one seems exactly right or wrong, just different. Stiller is on absolute top form here, less out-and-out comedian, more the lost-soul look he does so well when given half a chance. Watts, too, is terrific and Driver has every bit the commanding presence he will no doubt exploit to its full extent later this year in the Star Wars reboot.

One gets the feeling that a more self-indulgent Baumbach might have made this film more about the documentary form than it actually is — there are countless references to the authenticity of Process, including a memorable Jean-Luc Godard quote: ‘Fiction is about me, documentary is about you’, a conundrum that clearly plagues both Jamie and Josh — and very probably Baumbach. But it’s to the director’s credit that he reigns it in. While We’re Young is a story first and a genre exploration second — and it is far more enjoyable for the audience as a result.

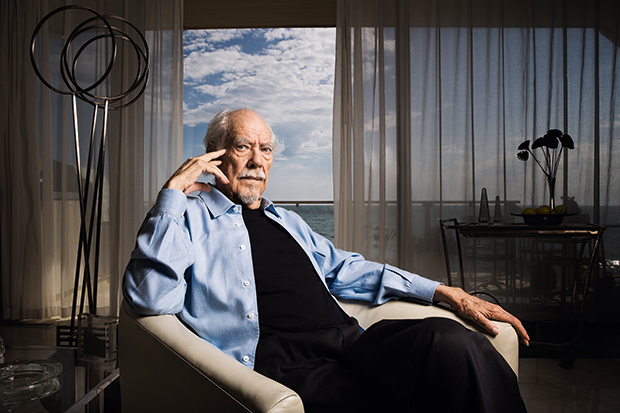

What does ‘Altmanesque’ mean? A variety of things according to the Hollywood starlets asked as part of Altman, a friendly, family-backed and home footage-filled documentary, which has none of the kind of genre play that Baumbach characters would enjoy and is instead a curiously straightforward portrait of a director known for maverick movie-making methods.

Elliott Gould, Julianne Moore, Bruce Willis and the late Robin Williams all line up with answers at the ready in an attempt to pin down the creative genius of Robert Altman, most of which feel as though they’ve been pulled from a thesaurus and none of which throws any real light on to the great director himself.

The man behind M*A*S*H and Nashville was nothing if not unorthodox. Hollywood’s bête noire, the American darling of Cannes and Venice, he favoured overlapping dialogue and a constantly moving camera. And yet, here, he appears more as a loveable grandpa, an accidental success with a heart of gold.

Archived footage of the man himself is interspersed with voiceovers from family members and friends, particularly his wife Kathryn, and he does make an endearing documentary subject. But it’s hard to see the fire for which Altman was so famous, and the film feels largely like an exceptionally well put together tribute, less the kind of unsettling investigation or quirky comedy Altman and his crew would themselves have admired. We never learn anything personal or troublesome about our subject, nor do we come across anyone with a bad word to say about him, which sadly leaves the film feeling uneven and distinctly unAltmanesque.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in