The veteran Russian historian Dominic Lieven’s new study of Russia’s descent towards the first world war is deeply researched, highly valuable in its focus on Russia, and unfailingly well-written: more proof of Lieven’s profound knowledge of the Russian empire.

One of his earlier works, Russia’s Rulers Under the Old Regime (1989), focused on the 150 men who ran Russia until 1917. Towards the Flame shares that work’s careful attention to a tiny elite of well-educated, cosmopolitan, mostly aristocratic men. With breathtaking directness, he says that fewer than 50 men (and it was all men) in Europe in 1914 took the decisions that led their countries into war.

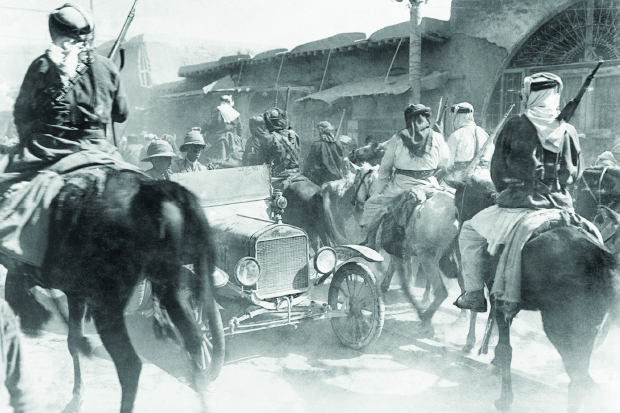

Towards the Flame starts with a few donnish chapters from what Lieven calls the ‘God’s eye view’. We learn about Europe’s struggles with nationalism, geopolitics and international economics. Though Lieven is not the first to say so, it is useful to be reminded that either Germany or Russia could have gained mastery of Europe by avoiding war and developing their industries instead. Russia was a giant in the making, before the calamity that was its 20th (and, arguably, the start of its 21st) century.

All too often, discussions of Russia in the period revolve around the fate of Nicholas II and his family, Rasputin and the revolutionaries. Lieven provides a welcome corrective, analysing Russia’s foreign policies as directed by little-known, if highly influential, individuals. He is excellent in his discussions of Grigorii Trubetskoy, Aleksandr Izvolsky, Alexander Benckendorff and Serge Sazonov; and their critics such as Petr Durnovo, Roman Rosen and Aleksandr Giers. His scope includes the emergence of the Triple Entente, the Balkan Wars (1912–13), the 1914 crisis and the first years of the war.

Throughout, one is struck by Lieven’s empathy with the elite he discusses. He sets himself apart by his knowledge of original memoranda, letters and memoirs, many of which can only be found in obscure Russian archives. He is unafraid of expressing his opinions on the arguments put forward by some officials before they were rejected or expropriated by the key decision-maker: Nicholas II.

An interesting and perhaps provocative aspect of Towards the Flame is Lieven’s rather old-fashioned view of how a society ought to be run. He sides with civilised individuals occupying key functions in a state’s apparatus, according much less importance to, in Russia’s case, power-hungry revolutionaries. When things go wrong, it is because the emperor or his officials have failed in their duties. Better government requires better education and intelligent responsiveness. Diplomacy and understanding, rather than bombast and force, are what make states truly great. There is nothing wrong, in other words, with an elite, as long as that group of individuals is honest and true.

Towards the Flame has a mostly sombre tone — as though Lieven were channelling Jeremy Paxman in his last years on Newsnight, rather than the bright geekiness of Evan Davis. It is sad to learn Lieven is battling illness and will probably not write another full-length study.

In the closing pages he considers whether America’s current decline, and China’s rise, stand a better chance of being managed without some form of catastrophe. He is not hopeful they will be, noting that the prospect of Europe’s destruction in 1914 did nothing to curb the aggression. It is as though he has seen too much of human stupidity not to doubt the prospect of civilised behaviour taking a leading role. The worst that can be said about Towards the Flame is that we should all hope Lieven, even as he’s right about the past, is wrong about the future.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in