I wonder what happened to my first edition of A Dandy in Aspic. I must have been careless about lending it when it could no longer be bought. Derek’s succeeding novels, from The Memoirs of a Venus Lackey (1968) to The Rich Boy from Chicago (1979), are in their place on my bookshelves; seven titles, lacking the first and ninth. The last novel, Nancy Astor (1982), based on his own screenplay, had passed me by. But it was A Dandy in Aspic, written in four weeks in a flat he shared with me and Piers Paul Read just off the Vauxhall Bridge Road in 1965, that changed Derek’s life.

Derek, Piers and I were friends but not a trio. We each had a room and kept to it. We had a kitchen but seldom ate communally. It was the year of ‘You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feelin’, by the Righteous Brothers: Derek played it on a loop. He went out most days because he had some kind of a job, and there were indications of an exciting life elsewhere. He’d met some people who had a rock band, and the band became The Who.

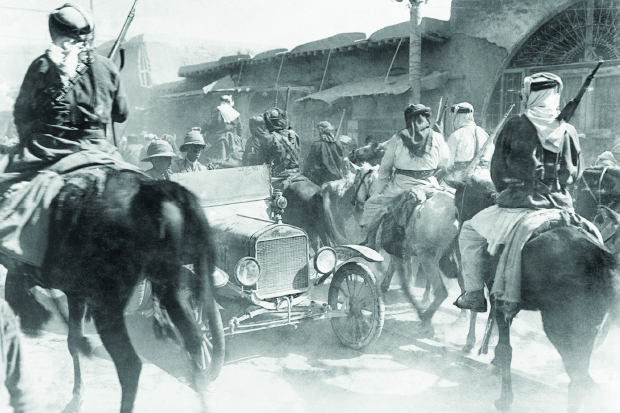

I’m writing from memory, an increasingly fallible resource, but my memory recalls that when Derek told us that he was writing ‘a spy novel’, we were sceptical. Surely that bandwagon had passed by? The Spy Who Came in from the Cold had been published years ago (three years seemed like a long time)! But what I do remember is that when Derek told me the basic premise for his novel (a spy with two identities who is ordered to kill his other self) I thought: now, that is an absolutely brilliant idea.

By that time, Derek had delivered his riposte to our scepticism. Gollancz, he announced one day, had accepted his book. The American rights and the film rights followed. By our lights, Derek was rich. Success had arrived.

The flat in Vincent Square was the third chapter of my times with Derek. We had met as tenants of bedsits in a house in Blenheim Crescent just off Ladbroke Grove, Notting Hill. Today those houses change hands for millions of pounds but back then, 1961 to 1964, Blenheim Crescent was the wrong side of a frontier between respectable Notting Hill and Rachmanland, so named after a notorious landlord whose fiefdom was rife with drugs and prostitution. London was getting into its famous Sixties swing, and Derek, a romantic figure in dark clothes, had a life of which I (a country mouse in the big city) knew little. I don’t think I was aware until later that he’d had at least a couple of plays modestly produced in London. But in 1964 we were independently invited, as promising young playwrights, to spend a few months in West Berlin with a group of young writers and film-makers, a ‘Literarisches Colloquium’ funded by the Ford Foundation.

That’s where we met Piers. Comfortably installed in a substantial house on the shore of a lake, the Wannsee, we young writers were left to do pretty much as we liked (to work, as was hoped). This extraordinary perk culminated in a kind of graduation evening of performances of the results of our fitful labours. My dim memory of Derek’s play suggests that it might have been the same piece, titled The Scarecrow, mentioned by Wikipedia as having been produced in London the same year. All I recall is the scarecrow and the unexpected (and effective) intrusion of a recording of ‘I Won’t Dance’.

From the first meeting in Blenheim Crescent to the last day in Vincent Square there were three or four years during which our lives conjoined. I think of him as slightly mysterious, slightly withdrawn, mostly keeping his thoughts to himself. But perhaps that was me. I have to concentrate to recall his laugh. Later, as married men, we saw each other at intervals at each other’s houses. Three of my copies of his books are inscribed, from 1970, 1976 and 1980.

In the late Seventies, perhaps (I don’t keep a diary), I stayed with Derek and his wife Suki at their baronial mansion in Gloucestershire (subsequently sold to a Rolling Stone). After their divorce he moved to Los Angeles, in 1989. One day in a bookshop on Sunset Boulevard, I saw him for the last time. He was, as ever, laconic, smiley, quiet, and darkly good looking. I should say something about that. Whether by his choice or by his publishers’, the early novels come without an author’s photograph. Among my ‘English firsts’, there is no photo until Somebody’s Sister (1974), his sixth novel. I remember Derek making a deprecatory remark about his looks, to the effect that he had a funny-looking face. I thought he was beautiful, with full wide lips, dark creased eyes, and a neat head of hair around a slightly flattened face, as if he’d run into a wall in a cartoon.

It was a hipster look which in itself didn’t give much away, but the mind behind the face was, and is, an open book; literally. The epigraphs of the novels come from Robert Browning, Hart Crane, Blaise Cendrars, Ford Madox Ford, William Empson, Walter de la Mare, C. P. Cavafy, Malcolm Lowry, Edward Gorey. Can one call the list disparate? To me, it evokes an aura of doomed romanticism in many guises. The names of characters — Mallory, Dowson, Hallam, Lytton, and others — seem not so much made up as borrowed from the same period piece, a scrapbook of country-house England before 1914. Derek’s favourite novels were The Good Soldier by Ford; and (the exception that proves the rule) The Great Gatsby.

Hemingway versus Fitzgerald was an argument we had more than once. Derek was a Fitzgerald man, and the books made the case for him, especially The Rich Boy from Chicago. Even the title sounds like Fitzgerald. That book’s epigraph is from a poem by Henry Bax, and perhaps it’s not fanciful to suppose that the four lines spoke more for Derek than did Browning and the rest …

In all forms of endeavour, private and public,

there are only two poles: sex and power.

Between these poles is a line called

the equator.

It is an imaginary line.

… because Henry Bax was imaginary, too.

It has been a fast 50 years since I used to hear Derek typing his way through A Dandy in Aspic, long enough for a reputation to wax and wane, and wax again. To be out of print is not a value judgment in itself, more like a hazard of the writing life. The novels were well received when they were new, and it’s good to see the first one back again. It will find and please new readers for a graceful writer and a graceful man who died too young.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

This is a foreword to Derek Marlowe’s A Dandy in Aspic. Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £9.49 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in