We know a great deal about Samuel Johnson and virtually nothing about his Jamaican servant, Francis Barber. The few facts of which we can be certain are these: born into slavery, Barber was aged about seven when his owner, Colonel Richard Bathhurst — who may, Michael Bundock suggests here, have been his father — brought him to England in 1750 and placed him in a Yorkshire school. Five years later, on his deathbed, Bathurst bequeathed Barber £12 and his freedom. It was Bathurst’s son who introduced Francis, now 12 years old, to Dr Johnson, whose wife had died two weeks earlier. Thus Barber spent his next 30 years in Gough Square, Bolt Court, and Johnson’s Court. In 1773 he was joined by his wife, a white woman called Elizabeth Ball who gave birth to four children, two of whom were apparently white themselves, and in 1784, when Johnson died, Barber inherited the bulk of his estate.

Opinions vary as to Barber’s character. Mrs Thrale and John Hawkins wrote nastily about his being an undeserving servant and a jealous husband (for which he probably had good reason), but Boswell, like Bundock himself, has only nice things to say about ‘good Mr Francis’. While Johnson described black men in general as coming low on the ‘human Chain of Beings’, he too expressed the highest opinion of Barber, on whom he came increasingly to depend.

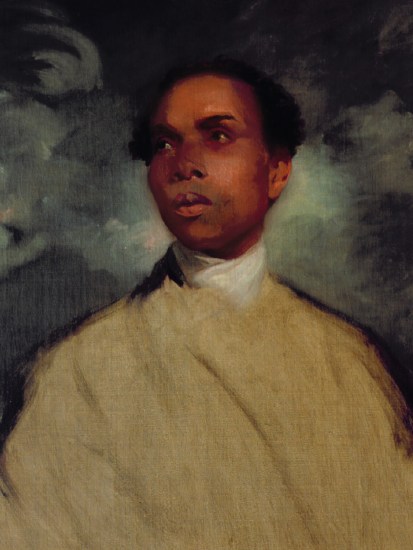

Built on this handful of facts and smattering of opinions, The Fortunes of Francis Barber is less a biography than a search for a missing person in which the cavernous gaps are filled with social history. Barber’s disappearance is so complete, Bundock suggests, that we cannot even be certain that the Reynolds portrait which graces the cover of the book (reproduced left) is either by Reynolds or of Barber.

Black servants were an 18th-century fashion accessory — Reynolds had one, too — but Samuel Johnson cared little for fashion, and nor did he require a man-servant. His house was run by the blind poet, Anna Williams, for whom Barber was an unnecessary irritant. Apart from Miss Williams, the household consisted of Mrs Desmoulins, the widowed daughter of Johnson’s godfather, a former prostitute called Poll Carmichael, the destitute quack Dr Levet, and the cat, Hodge.

Johnson himself escaped each week to the sumptuous Streatham home of Mrs Thrale, returning to the menagerie only on Saturday nights. In Human Wishes, his unfinished play about Johnson and Mrs Thrale, Samuel Beckett pictures the scene the doctor left behind. ‘You are knotting, Madam, I perceive,’ says Anna Williams. ‘That is so,’ replies Mrs Desmoulins. ‘I am knotting, my dear Madam, a mitten.’ Barber does not make an appearance, but it is as well to hold onto Beckett’s portrayal of the people he served and lived amongst because their sublime oddity is overlooked by Bundock.

Johnson described his house of lost souls as composed of ‘tolerable concord’ but ‘no love. Williams hates every body. Levet hates Desmoulins and does not love Williams. Desmoulins hates them both. Poll loves none of them’. Barber’s initial response was to run away. The first time, when he was 14, he ran down the road to Cheapside, where he worked for two years as an assistant to an apothecary; and the second time he joined a ship and went to sea, leaving his master distraught until he was safely returned.

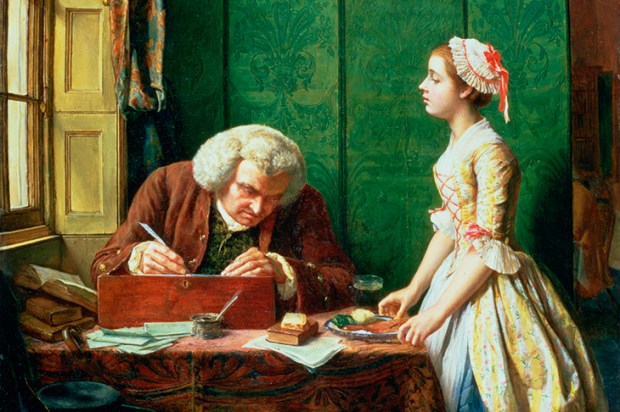

The relationship between Johnson and Barber was based, Bundock suggests, on identification. Both men were considered oddities: Barber for his colour — he was one of only 3,000 black people in London — and Johnson for his person. The great Cham believed himself to be monstrous; he walked, said Boswell, ‘as though in fetters’; even at ease, said Fanny Burney, Johnson’s body was in perpetual motion, ‘see-sawing up and down’, his hands twisting, his fingers twirling, his great head ‘rolling about in a strange ridiculous manner’. While the slight and nimble Barber waited at table, Johnson fell on his vittles like a beast at his prey, his eyes riveted to the plate, the veins on his forehead purple and swollen, sweat pouring from his temples.

Apart from serving the food, Barber delivered messages and answered the front door; to the horror of his friends, Johnson bought Hodge’s dinner himself so that his servant would not be demeaned ‘for the convenience of a quadruped’.

Following Johnson’s death, Barber’s annuity of £70 a year disappeared with astonishing and unexplained rapidity and he was reduced to selling his master’s former belongings. He died a poor man in 1801: whether his life had been a happy one is impossible to tell. Michael Bundock, a director of Dr Johnson’s House Trust, has produced a diligently researched and well-meaning book in which Francis Barber remains Gough Square’s invisible man.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £18 Tel: 08430 600033. Frances Wilson’s books include The Ballad of Dorothy Wordsworth and The Courtesan’s Revenge.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in