At the Turner Prize dinner of 2003, as the winner, Grayson Perry, took a photo call with his family wearing a girlish dress and huge bow in his hair, a German contemporary artist who was sitting at the same table leant over and hissed in my ear, ‘Only in England!’ He got it right in more than one way.

As time goes on it becomes ever more apparent that — in his combination of grittiness, eloquence and wackiness — Perry is very much in the national grain. He even manages to look like a sort of Identikit British archetype, resembling, in different images he presents of himself, Margaret Thatcher, Alice in Wonderland and Richard III.

No doubt, at some point in the future there will be a grand-scale overview of Perry’s work at the Tate or RA. But in the meantime, Provincial Punk, a medium-sized retrospective at Turner Contemporary, Margate, gives an opportunity to assess where he has arrived right now. He emerges as a late developer who has blossomed remarkably in middle age.

His first breakthrough came in the early 1980s, when he began to make and decorate pots. It was a brilliant move, partly because his paintings — as can be seen from some watercolours in the show — aren’t quite strong enough to make an impact on their own. By putting his pictures — violent, erotic and bizarre — on to an object as intrinsically retro as a handmade vase or urn, he set up an intriguing yin-yang conflict. This is summed up in the title of a piece from 1995: ‘Sex, Drugs and Earthenware’.

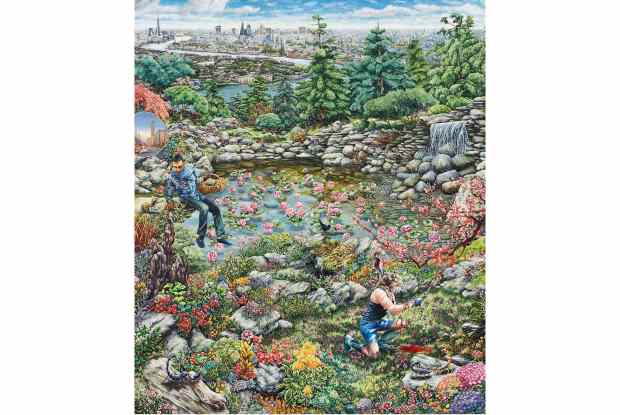

Perry was combining aspects of himself that he defined as ‘the twee and nostalgic side of myself’ — which is ‘a bit hobbity’ — and the mischievously aggressive punk. Those are two sides of British culture. On the one hand, we excel at pageantry, country villages and stately homes, on the other, rock music and squalor (think of Hogarth, Francis Bacon and Tracey Emin).

Perry superimposes these traits in one artistic personality, and — often — a single object. One ceramic, ‘The Chelmsford Sissies’, depicts the fate of Sir Thomas Sissye and his men, royalists who, defeated in the Civil War, were forced to parade through Chelmsford — Perry’s home town — in women’s clothing.

The pots, however, don’t coexist easily — as some works of art do not. Displayed alone, ‘The Chelmsford Sissies’ is a striking conceit, as is ‘The Huhne Vase’ (2014), dedicated to the former minister and covered with portraits of him, his personalised number plate, penises and the symbol of the Liberal Democrats. But a forest of such ceramics densely covered in slogans and complex imagery — which is what you find in the first room of Provincial Punk — is daunting to digest.

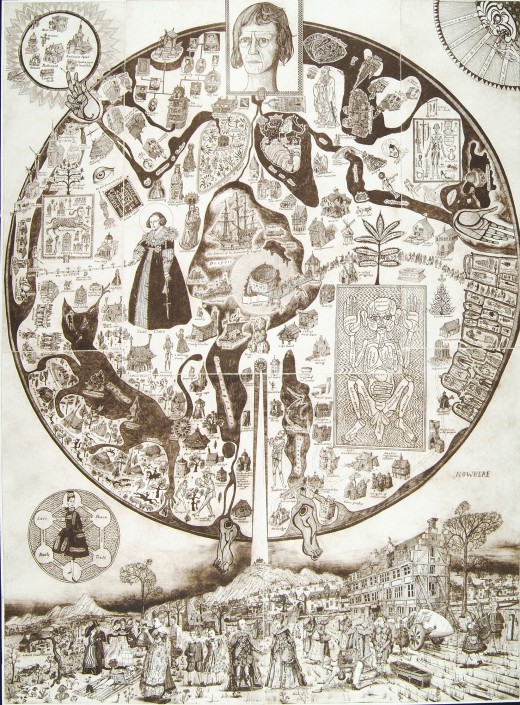

In 2003, when he won the Turner Prize, Perry still seemed essentially a one-idea artist. But in the past dozen years his work and public personality have diversified in an impressive fashion. In the succeeding rooms of the exhibition, there are full-scale tapestries, sculptures and — a particular favourite of mine — psychic maps. The last are based on 16th- and 17th-century prints, and present a terrain of hills, rivers and seas labelled with a scattering of 20th- and 21st-century references. ‘Map of an Englishman’ (2004), for example, charts the seas of Hyperactivity, Agoraphobia and Catatonia, the inlet of Narcolepsy, and the little towns such as Angst, Schadenfreude and Fear-of-Failure.

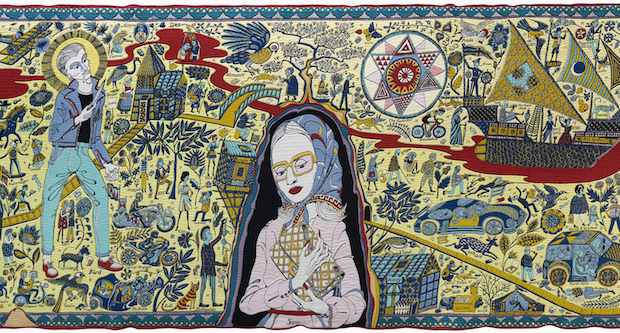

Recently Perry has unveiled ‘A House for Essex’ — his most nuttily ambitious project to date. This structure, a Hansel-and-Gretel cottage in a quasi-Slavic style sited at Wrabness at the mouth of the Stour, resembles a vision from what the comedian Lenny Bruce used to call ‘outer taste’. Inside, there are works recounting the life of a figure from Perry’s imagination: Julie, a mythical Essex social worker and former rock chick born on Canvey Island, who was eventually slain by a takeaway curry deliveryman’s motorbike in Colchester High Street.

Motorbikes and women — plus a Betjeman/Brideshead preoccupation with his childhood teddy bear — are part of Perry’s intricate inner world (another characteristically British feature of his personality). Further insights into his world are provided by some early films on show at Turner Contemporary, especially ‘The Poor Girl’ (1985), which involves a psychotic murderer and ‘a cult of women whose religion is consumerism’. Despite the evidence it gives of an idiosyncratic imagination, this — like so many artists’ films — is too amateurish to succeed. In the long run, Perry turned out to be much better at making things than movies.

He belongs to a long line of oddballs — including Blake, Lewis Carroll and William Morris — who amount to a tradition of their own. His achievement is that by putting the contradictions of his own sensibility side by side, he has made some new atlases of that elusive and much debated entity: Britishness.

I travelled back rather slowly on the high-speed train from Margate, via a long sequence of northern Kentish towns — Faversham, Sittingbourne, Chatham, Rochester, Strood. But it was easy to believe it was traversing the terrain of one of Perry’s maps, skirting the Sea of Delirium, stopping at settlements with names such as Baked Beans, Victoriana, Conspiracy Theories and The Sixties.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in