At the start of Canto XXI of the ‘Inferno’, Dante and Virgil look down on the pit of Malebolge, the Eighth Circle of Hell, in which sinners guilty of simony, hypocrisy and graft are punished. The last of those spend eternity immersed in a river of bubbling pitch. This sinister black liquid, the poet noted, looks much like the tar that Venetians boil up in their arsenal to smear over the hulls of their ships. Those lines came to mind more than once as I walked around the 56th edition of the Venice Biennale, not least because a large section is installed in the ancient buildings of that very Arsenale.

The Biennale is always the same — the crowds! the people! — yet always different. One vast section, as large as half a dozen ordinary exhibitions, is selected by a curator. In addition there are pavilions organised by individual nations — 89 of them, including debut appearances by among others Mongolia, Mauritius and Grenada. Then there are 44 ‘collateral events’. It all adds up to an array of art on an epic scale that can seem exhilarating as one sets off in the fresh light of morning in the lagoon, and almost punitive towards the end of a hot afternoon.

There was a moment when, immersed in inky darkness in the bowels of the German pavilion, I experienced slightly Dante-esque panic. I was trying to leave what was described ominously as a 60-minute video loop, when for a moment it seemed that beyond the exit, there was only deeper blackness and a padded wall. Trapped for ever in a contemporary art installation! Then, a little sheepishly, I found the door.

The official Biennale exhibition, entitled All the World’s Futures and selected by this year’s curator — Okwui Enwezor, a Nigerian — is a determinedly political affair: more Marx than Dante. Indeed, at the heart of the central pavilion in the Giardini, there is an auditorium designed by the architect David Adjaye in which the main event is a reading of the entire text of Das Kapital by a team of actors directed by Isaac Julien, an artist (I caught some of the preface to the second volume).

All the World’s Futures kicks off with about a quarter of a mile of art displayed in the ancient and magnificent warehouses of the Arsenale. The very first room contains a joint installation of works by Bruce Nauman and a French artist, Adel Abdessemed. The latter’s work, entitled ‘Nymphéas’, with a bitter nod to Monet, consists of starbursts of sharp machetes, opening like flowers of evil. Nauman’s neon pieces flash abrasive phrases: ‘Stick it in Your Ear, Sit on my Face’. One, shaped like a swastika, is entitled ‘American Violence’ — which tells you as much you need to know about the ideological slant of the All the World’s Futures.

I must confess that right-on agitprop is one of my least favourite modes of contemporary art. Partly, I object to its being so ineffectively self-congratulatory (it seems doubtful that a single vote has ever been shifted or a mind changed by an installation or art video). More importantly, it usually looks bad. Actually, that does not apply to the Nauman/Abdessemed room, which is powerful. But it does to most of the interminable rest of it.

There are a few scattered high points: a group of naked men painted by Georg Baselitz, dangling upside-down — much as Dante placed Pope Nicholas III, whom he encountered further on in the Eighth Circle. Steve McQueen contributes a compelling short film, Ashes, about the violent death of a young West Indian man.

Over at the central pavilion, there is another memento mori in the form of a group of paintings of skulls by Marlene Dumas. But the pickings are slim, and the whole reveals what Marx would surely have called the internal contradictions of the art world. All this political correctness, while outside the yachts of billionaire collectors are moored in a long line on the fondamenta.

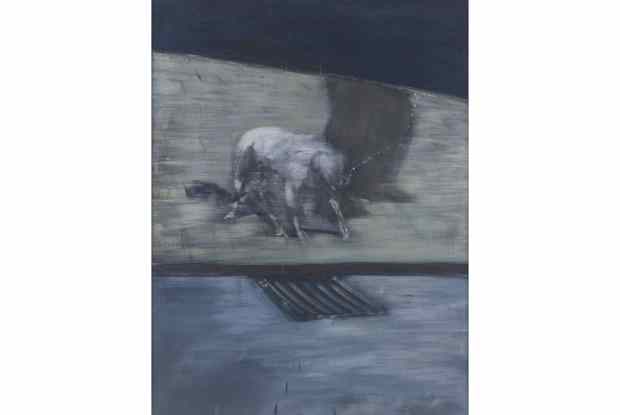

The pleasure-quotient is a little higher among the national pavilions. These are various — but follow certain trends. The late critic Hilton Kramer once told me that there were always tendencies at the Biennale (‘one year there were Francis Bacons from everywhere, Bulgarian Francis Bacons’). These days video art is ubiquitous, but not necessarily on its own — that’s becoming a little passé — instead it’s often projected alongside other stuff.

Among the better variations on this formula were works by Sean Lynch for Ireland and Joan Jonas for the US (the latter tells what turns out to be a rather straight-forward ghost story via multiple movies, drawings and objects). Another leitmotif is trees, dead, or, in the case of the French pavilion by Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, three living Scots pines complete with roots and large balls of earth, surrounded by galleries empty except for a loud humming noise (apparently electronically generated by the rustling of the trees themselves).

Piles of old clothes also turn up frequently, perhaps most effectively in Patricia Cronin’s ‘Shrine for Girls’, heaped on the altars of the little church of San Gallo, as a monument to the sufferings of young women in Africa, India and elsewhere.

Sarah Lucas, batting for Britain, stands out as an exponent of — relatively — old-fashioned sculpture. Her work largely depends on visual rhyme between body parts, private ones especially, and objects ranging from kebabs to stuffed tights. Outside the pretty neoclassical British pavilion, she has place an enormous tubular item, at once rampantly male, squalidly saggy and luridly yellow. There is more vivid yellow paint inside, together with a number of life-casts of the lower halves of women with cigarettes protruding from their intimate crevices. This last is outrageously daring, smoking being one of the few truly taboo subjects in the modern world. And the whole ensemble has visual pizzazz; on the other hand, it gives the impression of working a few ideas too hard: so only half marks.

In the traditional sculptural department, I preferred an installation by the Catalan artist Jaume Plensa in Palladio’s church of San Giorgio Maggiore. This consists in part of a huge human face, scanned from that of a young girl, and made from stainless-steel mesh, so it is at once transparent and present, material and immaterial.

A couple of my most delightful experiences, however, came from painting. Peter Doig has a fine array of new pictures in the Palazzetto Tito on Dorsoduro, including dreamlike but not quite surreal visions of pirates, fishermen and lions. In the 15th-century Palazzo Falier there is a splendid display of work by the abstract painter Sean Scully, his rippling stripes of colour evoking the waters of the Grand Canal outside the windows: much more paradisial than infernal, and somehow very Venetian too.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in