It would not have surprised their friends in the 1930s when Peter Watson had a fling with my grandfather, Robert ‘the Mad Boy’ Heber-Percy. Both gorgeous young men were known for their risky sexual escapades. What did ruffle feathers, however, was when Watson subsequently gave the Mad Boy a car. Cecil Beaton was so jealous that he demanded one too. And it was forthcoming: ‘Do please select any roadster which catches your fancy,’ replied the exceedingly wealthy Watson, who inspired lifelong unrequited love in poor Beaton. The Mad Boy’s long-term partner was Lord Berners, the famously eccentric composer, painter and writer, who retaliated by pinning Watson to the page of his wickedly satirical novel, The Girls of Radcliff Hall. The young men of his circle (including Beaton and the Mad Boy) were transmogrified, with little disguise, into schoolgirls cavorting in lesbian trysts. Berners himself appeared as the love-struck headmistress.

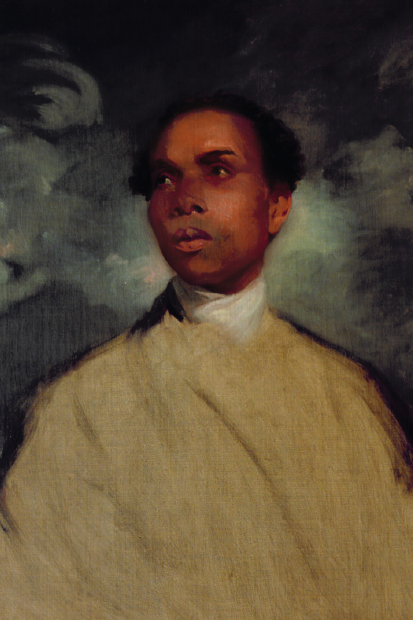

Lankily elegant, dressed in exquisitely cut double-breasted suits, and with the face ‘of a frog just as he is turning into a prince’, Watson wafts in and out of other people’s stories, never staying long enough to provide the full picture. He features in many biographies, notably Jeremy Lewis’s marvellous Cyril Connolly and Hugo Vickers’ s Cecil Beaton, but Queer Saint finally places Peter Watson centre stage. It tells the fascinating tale of his bizarre trajectory from extravagant 1930s playboy to a wartime saviour of the arts.

Watson disliked Eton, where snobbish whispers circulated that his father Sir George, was nouveau riche. He was. His Maypole margarine was so successful that by the time the 22-year-old Peter was sent down from Oxford, he was one of the richest men of his generation. Swanning about in a ‘coral-coloured Rolls-Royce inlaid with gems & with fur seats’ (Nancy Mitford’s description), Watson’s hedonistic youth was marked by his love of travel and his penchant for dangerous, beautiful young men, especially Americans. He was ‘essentially made for honeymoons and not for marriages’, as the poet Stephen Spender put it. His lasting dedication was to art and he collected Dali, Picasso, Braque, de Chirico, Klee, Miró, Ernst and Tchelitchew.

The war brought Watson reluctantly home from Paris to dreaded, dreary London, where his friend Cyril Connolly persuaded him to fund a literary magazine. Initially cool, Watson became a driving force behind the ambitiously intellectual Horizon, a publication that presented itself, with its purposefully dull cover, as a vital upholder of threatened western art and civilisation. Lasting over a decade, Horizon numbered among its contributors Orwell, Waugh, Auden and Betjeman. Connolly bought poems from Dylan Thomas for Watson’s cash, ‘as if they were packets of cocaine’.

A munificent benefactor to a swathe of brilliant young artists, Watson paid for the 16-year-old Lucian Freud’s tutoring and told John Craxton, ‘Find yourself somewhere to work and send me the bill.’ He collected British art and after the war, helped establish the ICA, still believing that ‘Art must be put into EVERYTHING.’ He annoyed some friends however, by refusing to behave like a ‘conventional rich man’ — voting Labour, relinquishing his car and rejecting luxury.

Adrian Clark and Jeremy Dronfield make clear that Watson’s discerning taste in art and clothes was not matched by his choice in men, revealing the often sad, occasionally sordid details of their subject’s relationships. The authors designate the ‘baddies’ and periodically descend into Daily Mail-ese, especially over Watson’s American boyfriend Denham Fouts. Truman Capote called Fouts the Best-Kept Boy in the World and Christopher Isherwood was also hooked by this drug-addicted ‘male whore and courtesan of extraordinary beauty’. The authors describe Fouts as ‘a Nazi’s Aryan wet dream made flesh’ who, leaving China, ‘finally slouched back to Europe, presumably having satiated his appetite for Chinese boys and Shanghai waterfront life’.

Queer Saint begins with a breathless murder mystery scene depicting the protagonist being found dead in his bath in 1956. Some supposed suicide, the court verdict was accidental death, but Clark and Dronfield imply that all will be revealed regarding a homicide. They finger a jealous boyfriend but, with little hard evidence, finally admit, ‘The truth about what went on behind that bathroom door would always remain elusive’.

Watson signed himself into the Mad Boy and Lord Berners’s Faringdon visitors’ book giving his occupation as ‘Animateur’.This is his best epitaph. Cyril Connolly (who adored Watson) wrote:

He stepped, gay and delightful, out of a charmed existence like a Mayfair Buddha suddenly sobered by the tragedy of his time to become the most intelligent and generous and discreet of patrons, the most creative of connoisseurs….

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £22.50 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in