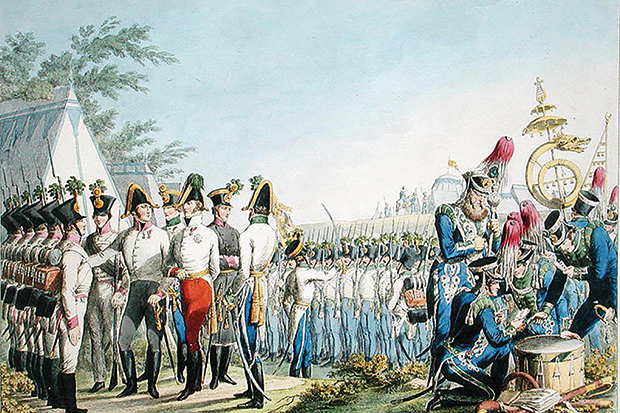

Earlier this century I was a guest at a fine dinner, held in a citadel of aristocratic Catholicism, for youngish members of German student duelling societies. My hosts were splendidly courteous, some of them held deadly straight rapiers or lethal curved blades, there were brightly coloured and golden braided costumes that made King Rudolf of Ruritania’s coronation robes seem dowdy, and we sung a rousing anthem about Prince Eugene of Savoy smiting the fearful Turk at the battle of Zenta in 1697. It was a high-testosterone evening. A few of my young hosts had duelling scars, discreetly placed so as to be imperceptible when they were in office suits, for some of them worked in Canary Wharf or the City as bankers, lawyers and accountants.

It is hard to transfer the excitement of such spectacles to the printed page. John Leigh is a Fellow of Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, an authority on Voltaire and the editor of the plays of Beaumarchais. His multilingual history of European duelling draws on his reading of novelists, poets and dramatists from Austria, England, France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Russia. There is also a diverting section on grotesque duels in Mark Twain and a brisk denial that the Wild West gunfights beloved by Hollywood film-makers can be ranked as duels: most of Wyatt Earp’s 150 victims were shot in the back. Touché is keen, clever, thorough, crisply humorous and impressive in its sources; but as its subtitle warns, it is a work of literary rather than social history. Readers in search of manly brio or real-life bloodshed will be disappointed. The book is a donnish paperchase, though an amiable one.

Duels, like parties, are handy episodes for writers, because they have premonitory openings, dramatic middles and conclusive finishes. Leigh characterises four types of duellist: the dutiful (gentlemen drawn by duty, but against their peaceable inclinations, into combat that they fear they will lose); the inveterate (quarrelsome men, who love strife, violence and flouting the law); the vain (showy libertines who want to cut fine figures); and the quixotic

(chivalrous men seeking justice).

Louis XIV led the way in 17th-century Europe in trying to suppress duelling. By the late 18th century Malta was singular in punishing men who declined to fight rather than those who did. In the 1760s a man who had evaded a challenge after a squabble over billiards was sentenced to life imprisonment, beginning with five years’ confinement in a Maltese dungeon without any light.

For those who disliked the progressive rationality of the 18th-century Enlightenment, duelling’s defiant diehard unjustifiability was alluring. The more gratuitous the pretext, the more admirably noble it seemed to this mentality. Humourists argued that duelling would be curbed by mocking its masculine posturing, but tragic deaths kept disrupting the farce. Duels became oddly respectable once the French middle classes took up swords and pistols against one another in the early 19th century. Whether fought with swords or pistols, duels were increasingly matters of bourgeois propriety rather than aristocratic pride. They were also used as screens for murderous resentment and suicidal despair that could not be openly acknowledged.

The earliest combat surveyed by Leigh is between Hector and Achilles. One of the last literary challenges was issued by the Southern gentleman poet Allen Tate to the critic Karl Shapiro in 1948. Between those dates, Shakespeare’s Richard II forbad combat between Bolingbroke and Mowbray, Lovelace was run through in Richardson’s Clarissa, Smollett’s picaresque character Roderick Random challenged Lord Quiverwit and broke his teeth, Sir Lucius O’Trigger fought Jack Absolute in Sheridan’s The Rivals, the ageing roué Vicomte de Valmont perished from the thrusts of the young chevalier Danceny in Les liaisons dangereuses, and Sir Mulberry Hawke met Lord Verisopht in Nicholas Nickleby. After quarrelling over whist, Phineas Fogg and Stamp Proctor had just cocked their revolvers at Plum Creek when their duel was halted by a Sioux attack.

Some of Leigh’s literary analysis – notably of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin – is abstrusely argumentative. But the short section discussing Merimée’s ‘Le vase étrusque’ — an elegant, ironical and neat story of fatuous idealism and callous worldliness — holds the attention and makes one wish to read the original. So, too, does Leigh’s treatment of duelling in those central European masterpieces, Joseph Roth’s Radetzky March and Gregor von Rezzori’s An Ermine in Czernopol.

Just months before his death in 1922 Marcel Proust sent his second to challenge a drunken youngster who had teased him for wearing a bowler hat and shawl in a night-club. And Ezra Pound once challenged the lyrical poet Lascelles Abercrombie: the latter’s choice of weapon was for each man to pelt the other with unsold copies of their works. There is no end to literary strife and the throwing of books.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £18 Tel: 08430 600033. Richard Davenport-Hines’s books include Auden, Sex, Death and Punishment and An English Affair.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in