You wait ages for a Labour leadership contest, then five come along at once. In the past few days, nominations have closed for the contests to be leader and deputy leader of the UK and Scottish Labour parties respectively as well as on the party’s pick for London mayor. Who wins these races will determine how Labour defines itself in opposition and how quickly it can regain power. Labour is in the dire position of being out of office at UK level, at national level in Scotland and at city level in the capital.

Labour should be taking a long, hard look at itself before deciding what to do next. Instead, it has a leadership contest in which sloganeering seems to be taking precedence over thought. The most incisive speech we’ve heard about Labour’s predicament was the one Tristram Hunt delivered as he announced that he was pulling out of the contest because he didn’t have enough support to get on the ballot paper.

All this could have been avoided had Ed Miliband listened to those who urged him to stay on as a caretaker leader, like Michael Howard after the Tories’ defeat in 2005. Howard took the chance to give all those running in the subsequent leadership contest prominent roles in the shadow cabinet and ensured that the race was long enough to give lesser-known candidates a chance to make their mark. The result was that the Tories picked David Cameron, not the early frontrunner David Davis, and returned to power at the next election.

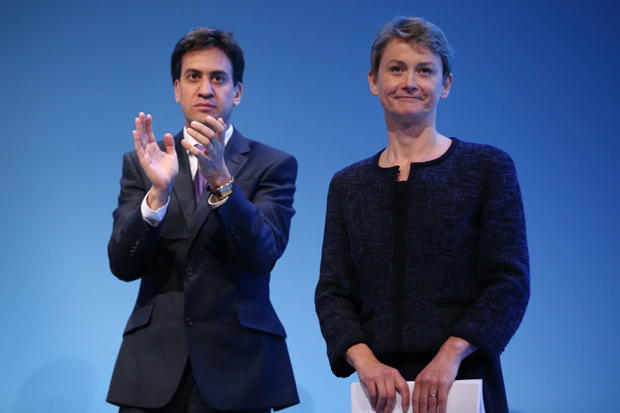

Miliband’s refusal to stay on, made all the more puzzling by the fact he has returned to speak in the Commons already and is regularly seen around Parliament, has dangerously foreshortened this contest. There are only four candidates on the ballot; one of them is there only because of nominations from those who don’t intend to vote for him; and Labour will have elected its leader before it meets for its first post-defeat party conference. If the Tories had followed this timetable ten years ago, David Davis would have become their leader.

The limitations of this contest are not just Ed Miliband’s fault. Gordon Brown succeeded in removing a generation of Labour talent from politics. Those who threatened his leadership prospects soon found that life in the Westminster kitchen became unbearably hot. So Alan Milburn, James Purnell and John Reid all hung up their aprons. To compound this problem, neither of the two Labour spokesman who have caused the most excitement among the architects of New Labour, the former paratrooper Dan Jarvis and the shadow business secretary Chuka Umunna, is standing.

These limitations are why so many in the party are intrigued by the possibility of forcing the new leader to submit themselves for re-election after three years. It’s a product not only of despair at the quality of the current field but also a Micawberite hope that someone will have turned up by 2018.

Liz Kendall is the most interesting of the four candidates. She is an unapologetic exponent of the reformist argument that ‘what matters is what works’. But she is painfully inexperienced; she has never even shadowed a secretary of state. There is also concern among some colleagues that while her policy approach might owe much to Tony Blair, her temper is rather too reminiscent of Gordon Brown’s.

Perhaps Kendall’s biggest mistake has been to confront the party with too many hard truths at once. It is worth remembering that in that 2005 Tory leadership race, Cameron did a lot of reassuring — saying he wanted marriage recognised in the tax system and the like — before setting out how his party needed to change to win.

Such problems with the Kendall candidacy have given Yvette Cooper momentum. She now seems the woman best placed to block the current favourite, Andy Burnham. One Blairite told me this week, ‘If you want to stop Andy, you’ve got to back Yvette. She’s the only one who can do it.’

If the Labour leadership race is dispiriting to those on the reformist wing of the party, then the deputy leadership race is downright depressing. The frontrunner at the moment is Unite boss Len McCluskey’s former flatmate Tom Watson, who has the most nominations from MPs. Watson’s previous claims to political fame include his involvement in the coup against Tony Blair and his campaign against the Murdoch press. James Purnell called him ‘a cancer at the heart of the Labour party’. He is a divider, not a uniter. But he may well gain control of the Labour party machine as deputy leader. It’s worth noting that it was Watson’s judgment that led to scores of activists descending on Sheffield Hallam for months in a predictably unsuccessful attempt to defeat Nick Clegg, while 50 minutes up the road Ed Balls’s seat was slipping away.

Perhaps the great devolved centres of power could offer Labour a route back. Next year’s Holyrood elections in Scotland will probably come too soon for any kind of Labour revival. The party should elect the 33-year-old Kezia Dugdale leader only if they are prepared to let her lose an election (or two). The Scottish National Party surge will not recede in the near future.

In London it seemed almost inevitable that, after Boris, City Hall would go red again. But Zac Goldsmith’s entry into the race has changed that. He is a unique Tory. He can be confident he’ll gain both Green and Ukip second preference votes. Polls already indicate that he would end up in a dead heat with Sadiq Khan, the union-backed candidate who ran Ed Miliband’s leadership bid. But Goldsmith is currently trailing Tessa Jowell, the former Olympics minister who helped bring the games to London.

It is not certain that Jowell will win the Labour nomination. She is fighting by Queensberry rules in a contest that is already turning dirty. If she is to win the nomination, her team must wise up to the battle that she is engaged in.

Those who say that Labour will be out of power for a generation are forgetting how long a time in politics five years is. By 2020, the EU referendum and its aftermath could have torn the Tories apart. But the challenge for Labour now is to gets its house in order, so as to turn itself into a credible alternative. So far, there are few signs that the party understands quite how much work needs to be done.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in