With a career of more than 60 years so far, Frank Auerbach is undoubtedly one of the big beasts of the British art world. His personal reticence, however, and the condensed, impacted idiom of his painting have contributed to his enigmatic, somewhat opaque reputation. Catherine Lampert, who has sat regularly and patiently for him since 1978, is uniquely qualified to throw light both on the man and his art, but the tactics she employs here are very different from those of Martin Gayford in Man with a Blue Scarf, his intimate, engrossing account of sitting for Lucian Freud.

Matching Auerbach’s reticence with her own, she keeps herself largely out of the story, focusing instead on observations made by the artist over the many decades of his career. These she patches together with her own comments into a composite picture as nuanced as any of Auerbach’s own portraits, fruit as they are of many years of working and reworking, trial and error, building up and paring down.

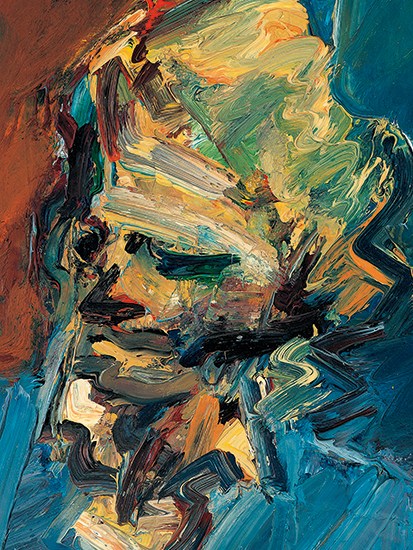

Auerbach’s range of subjects is deliberately narrow — street scenes round Camden, portraits and interiors, each new painting emerging from a profound engagement with the familiar. He searches deep rather than ranging wide, rooted firmly in the studio, painting the same handful of lovers and friends obsessively over the decades in dizzying swirls of impasto. He only travels if he has to, invited abroad by a museum, gallery or biennale; when once challenged on his lack of daring he replied:

The daring I’m talking about is simple daring in painting. I’m naturally timid. I’m frightened of heights, I can’t swim, I can’t drive, I’m afraid of large dogs. It seems to me to be sensible to avoid the seaside, bridges and alsatians. Painting is a relatively safe way to be courageous.

And amidst the intense seriousness of his daily quest to nail the very essence of his subject in those vertiginous (and daring) encrustations of paint, he is ‘just having fun in the studio … I’d rather do that than go to the theatre or sit about’. Painting is like a game for him, he claims, ‘something like chess, games with an infinite set of possibilities and difficulties’, and he keeps on working ‘in the hope of finding this result which to me is surprising, more surprising than finding an Easter egg as a child’.

Many have speculated on where Auerbach’s rootedness and self-confessed timidity originate, and Lampert has discovered all she can about his childhood. In 1939 the seven-year-old young Frank was dispatched from Berlin to an agreeably eccentric school in Kent called Bunce Court by his over-protective Jewish parents, who subsequently both perished in Auschwitz. Surprisingly, Frank embraced his new life with gusto, never enquiring about his parents’ fate: ‘I did this thing which psychiatrists frown on,’ he later admitted: ‘I am in total denial … I came to England and went to a marvellous school, and it truly was a happy time. There’s just never been a point in my life when I felt I wish I had parents.’ Through sympathetic teachers he discovered first theatre, then art (David Bomberg a key early influence), and his dogged, unswerving course was set.

Lampert is revealing about the relationships that form the centre of his life and work: with models Stella (E.O.W.), Julia (J.Y.M.) and his son Jake; and with Bacon, Freud and Leon Kossoff, in whose family bakery Auerbach found work manning the bread counter, while Leon sold cakes. (Money was once a constant worry, and Frank apparently subsisted on rice, lentils and tahini till he was 50.) Despite their many differences his friendship with Freud, seasoned by their Berlin childhoods, entailed a love of large breakfasts and a profound mutual respect; I well remember Freud deferring to Auerbach’s advice and re-hanging an entire exhibition of his etchings at the Marlborough Gallery.

Auerbach may be steeped in the work of the Old Masters, Titian in particular, and his debt to Vuillard and Leger evident in his paintings of interiors and building sites, but he maintains, ‘although we may be stimulated by works of art we make our pictures from living sensations. The aim of painting is this: TO CAPTURE A RAW EXPERIENCE FOR ART.’ That raw experience, the fons et origo of his practice, is deftly presented here, and the art duly illuminated.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.96 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in