The campaign to keep Greece in the euro has resulted in five years of groundhog days. The unfortunate country seems to be forever approaching a day of repayments it cannot afford. Ministers and diplomats assemble to thrash out a deal. Meetings collapse in bad temper, and markets sink. Then, at the eleventh hour, a deal is somehow forged. Greece agrees to reforms which seek to cut spending and balance the books in return for billions of pounds of bailout cash. Markets rebound. The money is paid, the debt repayments met. And then all starts to go wrong again. A few months later we are back where we began.

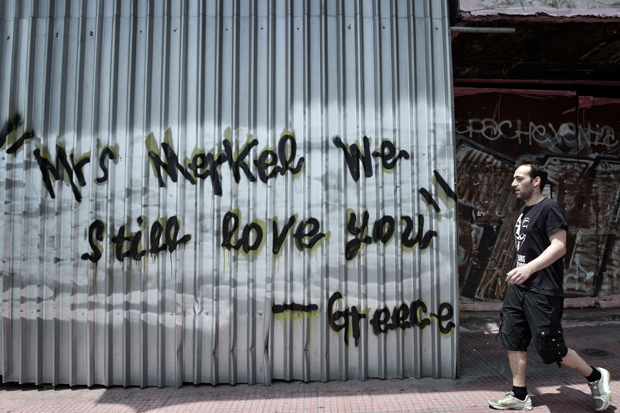

Anyone who hoped the election of Greece’s Syriza government in January would break the cycle has been disappointed. All that has happened is that tempers have worsened as the unpayable bills have grown larger. The new Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, this week rounded on Greece’s creditors, accusing them of somehow ‘pillaging’ the country in their expectations of repayment. He has used his election victory to claim a mandate for a path of ‘anti-austerity’ — i.e. bigger bailouts and weaker conditions. But while he can claim a mandate from his own electorate, he has none from the Germans, the French, nor any other country whose people are paying the bills.

Mr Tsipras is right that the past five years have been a disaster for the Greek economy. It has shrunk by a quarter. Unemployment stands at 27 per cent. The bailout cash — €240 billion to date — has yielded an even more miserable return than the aid lavished on kleptomaniac regimes in developing countries over the past few decades. Greece’s military spending, however, puts Britain to shame: it seems to have no problem with spending more than 2 per cent of its economic output on the armed forces. Tsipras may like to confront the Germans, but he appears to know better than to antagonise his country’s colonels.

It’s clear how Tsipras hangs on to power, but not so clear why the eurozone wants to hang on to Greece. If eurozone leaders had not invested so much in the survival of the single currency grand projet, they would long ago have started asking the unaskable: would it really be such a bad thing if Greece’s membership of the euro ended? If the drachma were brought back, its value would plunge; then Greek goods and services would become cheap on world markets. Greek holidays would become deliciously good value. This is the purpose of a country having its own currency: it’s the most powerful tool to ensure recovery after a crash.

As Britain knows. In 1992 we were deep in recession, and much political energy was unwisely expended in trying to remain in a currency straitjacket that was making matters worse. At the time, all conventional wisdom insisted that Britain must stay in the so-called Exchange Rate Mechanism, a precursor to the euro. (The Spectator had been the only publication urging the Conservatives to keep out of the ERM.)

When the inevitable happened on Black Wednesday and Britain crashed out of the ERM, it was viewed as a day of national humiliation. But our long and bountiful economic recovery started then — which is why so many economists now refer to it as ‘White Wednesday’. This is what Greece now needs.

The short-term consequences would of course be painful. Greeks who have not moved their savings offshore would see their value plummet. Investors in Greek government debt would suffer defaults, yet the assertion that the German government is only propping up Greece for fear of its own banks going bust is not true. According to JP Morgan, Germany’s two main commercial banks, Commerzbank and Deutsche Bank, have exposure to Greek debt of €400 million and €298 million: containable losses even if the whole lot were wiped out.

However damaged, the Greek economy would finally be in a situation from which it could recover. Of course Greece would only be rejected from the eurozone, not the EU; it would retain all the benefits of the single market, and would be in a better position to exploit them.

Currency unions do not work unless there is full political and economic union. Were Greek and German taxes to be aligned, equally rigorous budgets imposed in each country, and the same approach to corruption and enforcement of tax law to be adopted, then maybe the two countries could function on a single currency. But the Greeks would like the imposition of German financial and legislative discipline even less than they like the bailout conditions being placed upon them now.

So great is the euro-hubris that the Greek experiment is destined to be repeated elsewhere, as other member states find themselves out of kilter with Germany, the dominant eurozone economy. The beauty of Europe lies in its diversity: it’s hard to think of any group of developed countries that have less in common with each other. Still, the eurozone lacks people who are prepared to admit that the whole single currency experiment has been a ghastly mistake. Until they are heard, Europe is destined to suffer a long series of repetitive crises.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in