This is a thriller, a novel of betrayal and separation, and a reverie on death and grieving. The only key fact I can provide without giving away the plot is that Caroline, the film-making wife of Michael, the novel’s main protagonist, is killed in the badlands of Pakistan by a drone controlled from a facility near Las Vegas. Caroline is filming Taleban leaders when they and Caroline are killed. Michael, who is ‘an immersive journalist’, has spent some years on a project with gangs in the Upper West Side of Manhattan. It is dangerous but rewarding work, and after a few years his findings are published to some acclaim under the title of BrotherHoods.

Now back in London, he falls in with Josh and Samantha, neighbours in the adjoining house and flat on Hampstead Heath. Their marriage is in a precarious state, and Michael’s proximity seems to help. But their relationship spirals swiftly into hatred when there is a catastrophe in their family.

This probably sounds enticing, but there is a problem. Owen Sheers doesn’t appear to subscribe to the first commandment of

novel-writing — to show, not tell. His style is mostly telling; not only that, but he often repeats — slightly revised, but never with greater clarity — the previous sentence, which verges on the pointless. In fact it becomes irritating. Many of his observations are dull, or offered by rote, and he goes in for highfalutin prose, such as:

In cafés, crowded pubs, sometimes even in the street, they came to her, recognising her brevity as if she were a comet they knew would trace their nights only once in a lifetime.

And:

As Michael neared the bath, he closed in on that memory again, until, without any disturbance of translation, he was no longer alone and Caroline was there too, naked in the bath, looking up at him, and he was looking down at her brown and gold eyes and her fine-featured face.

As a description, ‘her fine-featured face’ really short changes the reader. It is the author’s task to make his work lucid and cogent. Sadly the book is full of this kind of thing, so that I wondered whether the narrator wasn’t correct when he says that ‘fiction had continued to elude him’.

The plot concerns the lives of Michael’s friends and their marital ups and downs; and Michael tries to find out who killed his wife — from a distance of thousands of miles. The best passages concern this aspect of the story. But even here it is too cluttered and dragged down by repetition.

The book reads as though it were rushed. A lot more showing is required if we are to form our own judgments on the characters. As written, they are barely memorable —never allowed to develop without Sheers interposing between them and us.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

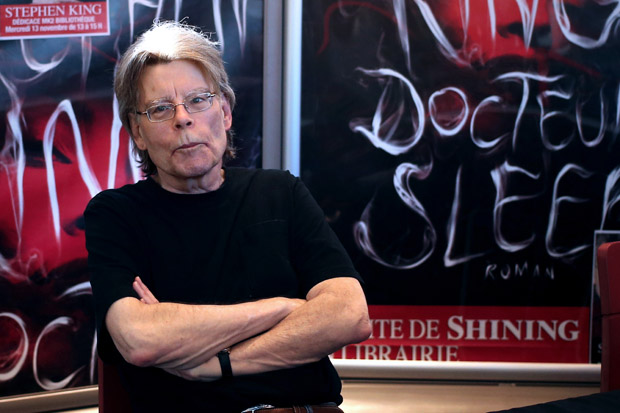

Justin Cartwright’s books include Other People’s Money, The Promise of Happiness and Lion Heart.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £12.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in