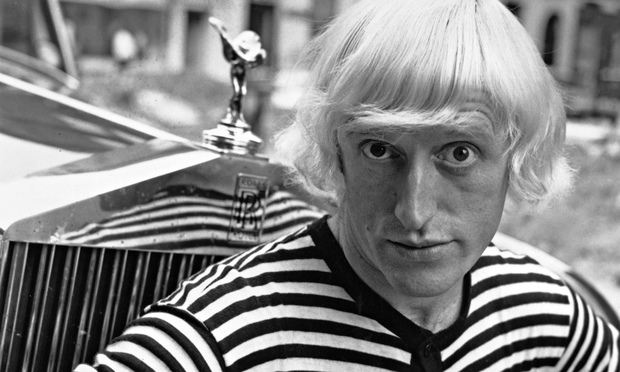

Have you heard the one about girlfriend-killer Oscar Pistorius not having a leg to stand on? Or what about the Germanwings knock-knock joke? If you find gags like these funny, you could come and stand with me on the terraces at Brentford FC. When we played Leeds United earlier in the season, we chanted at them, ‘He’s one of your own, he’s one of your own, Jimmy Savile, he’s one of your own.’ The general public has never wasted much time making up jokes about tragic public events.

Making light of high-profile tragedies is a perfectly understandable human reaction, even if it might be frowned upon by some. And what about those who seek to turn topical events into serious art? Is that any more noble than making a cheap joke? It’s a question that’s worth asking in the light of the fact that a new play at London’s Park Theatre is about to exhume the aforementioned Savile, while details of the full extent of his criminality are still emerging.

An Audience With Jimmy Savile tells the story of the cigar-chomping perv’s crimes, which included attacks on hundreds of children and women, from the point of view of one of his victims. With its controversial subject matter and a household name, the impressionist Alistair McGowan, in the title role, the production seems ripe for a tabloid-stoked outcry. Yet its author Jonathan Maitland, a journalist with 30 years experience who currently works for ITV’s Tonight programme, tells me it is not too soon for a Savile play and there is yet to be a serious backlash.

A quick check online shows that he seems to be right. There’s an e-petition, one of those digital moron magnets, calling for the production to be scrapped that has so far attracted only a couple of hundred signatures. Maitland has, he admits, had to answer a number of critics on Twitter, but insists he was able to persuade them he is not exploiting the subject matter. In one exchange he got one man to change his hashtag from #fictionalisedforprofit to #goodluck by explaining he would be donating a considerable chunk of any profits to a charity that supports victims of abuse.

And what about Savile’s victims? Maitland reveals that one of the survivors of Savile’s abuse did come forward to complain, but following a discussion with Liz Dux, a lawyer representing 168 of the other victims, their fears were allayed. Dux, whom the playwright consulted, told that person what Maitland is telling me now, that the play is not a musical or a comedy but a serious and sober examination of what went on. ‘I used my in-built radars of taste and decency to decide what I would and wouldn’t portray on stage,’ he says. ‘For me any visual representation [of the abuse] was out of the question. If I had written this when I was younger, I might have been fatefully undermined by a dangerous desire to shock and that is so not what this is about.’

An Audience With Jimmy Savile arrives in the same month as the film adaptation of London Road, the National Theatre’s dramatisation of the Ipswich prostitute murders of 2006, is released in cinemas. That show also caused a stir when it was first announced but the quality of the production silenced objections. How good the Savile play is remains to be seen, of course, but Maitland’s case for the production to exist is put forward forcefully. He calls it a ‘public service form of journalism’ telling ‘one of the most important stories of our lifetime because it impacts upon so many things: our attitude to children; how we handle abuse; cravenness before celebrity; limitations of the libel laws’.

‘When my previous play Dead Sheep [about Geoffrey Howe’s political assassination of Margaret Thatcher] was on last year,’ he adds, ‘I found that drama could be as, or possibly more, effective than a purely factual programme. Without wishing to sound pretentious, it can shine light on darker truths than a purely factual format can get at.’

Maitland is right about this. Plays, films and TV versions of real events can hold more of a sway over public perception than the news. And so, in this respect, with victims and their families to consider, it’s surely appropriate that he has been ‘almost paranoid’ about adhering to the truth when creating his drama. For other artists and writers, though, veracity is not so important. Take James Ellroy as a prime example. Talking about his approach to representing 20th-century American history in his novels, he has said, ‘I want to be fairly true to the real-life people …And then I want to have fun with it and fuck with them.’

Context and timing are important. It’s obviously easier to mess with history than with current affairs, but that’s not to say that partial and disputed versions of recent events haven’t and can’t be created. The difficulties that can be caused by this approach are sometimes serious. Jamie Bulger’s mother objected to The Age of Consent, a 2001 play about a child killer that appeared to use her son’s murder as its inspiration. Some examples are not quite so grave. My granny, for example, hated Roman Polanski’s The Pianist because it made a hero out of Wladyslaw Szpilman, a man she knew personally and thought was a berk.

A further example is John Adams’s opera The Death of Klinghoffer, about the murder of the wheelchair-bound Jewish-American Leon Klinghoffer by Palestinian terrorists in 1985, which has been causing controversy since it was first performed in the early 1990s. Klinghoffer’s daughters Lisa and Ilsa utterly despise the piece and when the Met revived it last year the programme included a statement from them in which they said it ‘offers no real insight into the historical reality and the senseless murder of an American Jew’. It ‘sullies the memory’ of their father, they added.

In a thought-provoking article for the Jewish Chronicle, the critic Norman Lebrecht, considering the vexed question of The Death of Klinghoffer’s alleged anti-Semitism, wondered whether the public might want Lord Leveson to take a look at the arts and aid people who feel their privacy and pain has been exploited in the name of entertainment. Trying to impose any statutory regulation on the arts would, of course, be as foolish as trying to do the same for the press. Freedom of expression is to be clung to at all costs, even though it offers no protection or comfort to the likes of the Klinghoffers, Denise Bulger or, say, a victim of Jimmy Savile’s abuse who might find a dramatic representation of the man’s crimes unacceptable under all circumstances. A satisfactory answer for them might never be possible. The occasional personal injury is the price that must be paid for living in a society that is at liberty to sensitively represent, ‘fuck with’ and even make crass jokes about the terrible things that happen.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

‘An Audience with Jimmy Savile’ runs at the Park Theatre from 10 June to 11 July (www.parktheatre.co.uk)

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in