As I got into a Brighton taxi this morning, my driver’s first words were ‘apparently it’ll clear in a couple of hours’. I gathered — of course — that he was talking about the morning mist. ‘It’s almost gone already up in town.’ A conversation about weather prospects is hardly uncommon in British taxis, and we launched into this one with no preamble at all (he hadn’t said hello), as though invisibly picking up the thread of a conversation already in progress, a perpetual, life-long discussion about whether it’ll rain tomorrow filling in as the default whenever nothing else is being said.

It’s odd. And in The Weather Experiment, Peter Moore tells us how we got here. His subject is the 19th-century development of meteorology, a complicated fits-and-starts evolution rather than a hurtling meteoric rise (shame: that might have made a passable joke for a reviewer), taking in scientific and technological advances but also character, circumstance and controversy, intrigue and coincidence.

Well into the 18th century, navigators and ‘scientists’ (a word of somewhat different meaning then) were learning their meteorology from Aristotle. Naturally, people were in a constant state of experiencing the weather (there’s always been plenty on these islands), but without a systematised way of recording or measuring it (the most evocative descriptions of, say, clouds, were those employing literary rather than scientific skill), still less processing information in order to predict the future. And even if such calculations had been possible, one still couldn’t make the information travel speedily enough to be useful. Weather systems can easily outpace even the fastest horses. So while in other fields the thinking that valued classification and measurement was increasingly well-established, only the sky remained defiantly unclassified; the heavens were simply not part of the taxonomists’ domain.

It took a series of curious, eccentric and fiercely determined men to change that. They sought to gather information, to record, analyse, and make predictions based on it, and to do it in the interests of science, yes, but also for moral reasons, and patriotic ones. Moore’s writing animates these men well. Among them was the energetic Francis Beaufort, whose early life saw him watching the world from a crow’s-nest — he would become a navy hydrographer, and with his sharp empirical mind would develop systems for measuring wind strength.

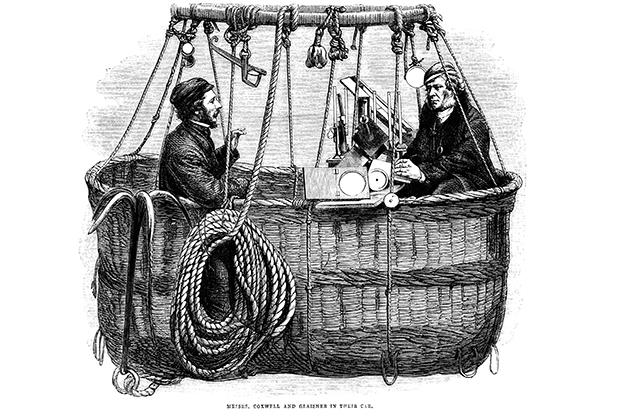

There was cool-headed James Glaisher, who in July 1862 boarded a balloon called the Mammoth, carrying a list of observational questions and a huge smorgasbord of measuring instruments (thermometers, barometers, hygrometers). Travelling seven miles up into the atmosphere (a newly current word), quite uncharted territory, Glaisher almost lost his life — a gripping moment in the story — but managed, nonetheless, to continue calmly recording meteorological observations throughout the drama, resolutely unfazed by the evident mortal peril.

Moore’s central figure, however, is Robert FitzRoy, of whom this book offers, almost incidentally, a fine and complex character study. Through his most famous incarnation as captain on the Beagle to his time as admiral and his shocking, sad end, we watch a brilliant, restless man, who instigates an innovative mission to create a public weather service. Following a violent storm that wrecked a steam-clipper on Anglesey in October 1859, FitzRoy finally insisted the government needed to invest in a storm-warning system. By 1861 he was gathering information by telegraph and sending the first warnings out to coastal stations, and soon his forecasts — importantly not ‘predictions’ or ‘prophesies’ — were being run in newspapers, too. Needless to say, these weren’t 100 per cent reliable; the authority of the system was soon being undermined. (Remember how my taxi driver used that word ‘apparently’?)

The Weather Experiment assembles seven decades of progress, comprised of sometimes quite small personal, political or scientific moments that inch the world closer to where we are today. It’s a skilful, detailed account of a complex story, in which scientific advances are far from inevitable in a world of flawed humans and bad luck. FitzRoy himself would live to see the reputation of his work flounder. Today, however, he has a patch of shipping forecast sea all to himself — Biscay, Trafalgar, FitzRoy, Sole… — a tribute from today’s meteorologists to him and his fellows on that journey.

Peter Moore’s engaging, often surprising work of storytelling, written with such care and pleasure, is a fine tribute to their achievements, too.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in