There’s a scene in 887, Robert Lepage’s latest show, which opened at the Edinburgh International Festival last week, in which the French-Canadian director stands alone in his kitchen, lit up by the glare of his laptop, watching his own obituary. Three beers sit on the work surface and he has a fourth in his hand. As it plays, he tuts, peeved that three decades of visionary theatre merit merely two minutes of screen time — inaccurate, at that.

Even if his reputation has waned in recent years, Lepage is still considered one of the world’s great theatremakers. A slashie before slashies were slashies, he writes, directs and designs his shows — often performing in them as well — and the best of them slip down with a shimmering, magic-eye theatricality: tumble-driers morph into space stations and shoeboxes turn into cities. His stories are grand, globetrotting epics encompassing vast clouds of associated ideas: The Seven Streams of the River Ota (1994) wove Hiroshima, the holocaust and the Aids crisis into a treatise on death in the 20th century; The Far Side of the Moon (2000) condensed the space race into a tale of two brothers.

However, Lepage is not considered the force he once was. It’s 20 years since he was last part of the Edinburgh line-up, with his one-man staging of Hamlet, Elsinore — strange for a mainstay of the international festival circuit. The year before had proved controversial: a work-in-progress of The Seven Streams wasn’t billed as such and audiences weren’t best pleased.

‘People say, Oh you’ve been pouting,’ Lepage says, perched on a cream sofa in an empty foyer. ‘No, I’ve not been invited —probably because there are trends in theatre. There was a time when my work was a little more fashionable. This is a great festival: an antenna for what’s going on in the art world and maybe other people were more on-trend. Now, the swing is coming back. People are interested in what I’m doing again.’

Certainly, 887 marks a return to form for the French-Canadian. His first solo show in almost a decade, it muses on memory, and the relationship between personal lives and public history — hence his fretting about legacy alone in his kitchen.

It’s a madeleine of a show. Lepage takes us back to his childhood home, a Quebec City apartment block, 887 Avenue Murray, which appears on-stage as a giant doll’s house complete with wrought-iron railings and Lilliputian neighbours. The Lepages lived on the third floor, cramped into too few rooms, after his grandmother moved in on account of Alzheimer’s. His father, who served in the navy during the war, was a taxi driver; his mother looked after the four children.

Autobiography has always underpinned his work — the two space race brothers represented split sides of his personality — but this is the first time Lepage has appeared as himself on-stage. ‘I’ve been wanting to do that for a long time,’ he explains. ‘It’s fairly pretentious to come out and say, I don’t need a mask. I’ve always been afraid that people would deem that self-indulgent.’

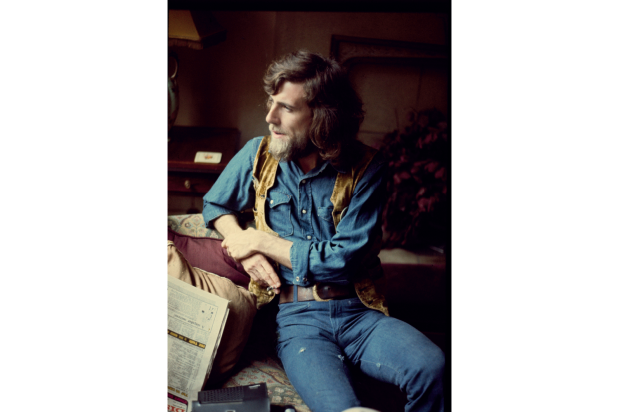

Lepage is a man of contradictions: narcissistic enough to try to appear otherwise; a self-proclaimed ‘liberal pessimist’, who wants change but can’t see it happening; an auteur who came to theatre as ‘a collective form of expression and a nice way to hide behind other people’. On-stage, he cuts an imposing figure: his squid-ink hair darker and more definite than his charcoal three-piece, beneath which he wears a tight, toning T-shirt. When he takes his shirt off, he’s surprisingly hench for a man of 57.

In person, he’s softer — a blue short-sleeved shirt gives him the air of a holidaymaker, and his face is gentle but intriguing. His features have a sci-fi quality that takes a while to pin down. Alopecia means he has neither eyebrows nor eyelashes, making him seem androgynous and ethereal.

His work is worldly, though. Alongside autobiography, 887 looks at Quebecois history, specifically the separatist movement of the 1960s, when the Front de libération du Quebec was at its most active and bombings, kidnappings, even killings were commonplace.

Lepage’s version of events, swirled with childhood memories, diverges from the accepted pro-federalist narrative. The conflict, he says, was not about nationality. ‘It was about something else. It was a class struggle.’ His taxi-driver father is a symbol of that, connecting the personal and the political. ‘I never thought he’d be a major protagonist in the piece, just as I thought he wasn’t a major protagonist in my life.’

Today, Lepage calls himself ‘an occasional separatist. I still believe that an independent Quebec would be a great thing, but of course, the reasons people want independence today are radically different. That’s why I felt the urge to show the origins of the argument.’ That, of course, gives the piece special resonance in Scotland.

Lepage’s position is clear: he’s with the ‘Yes’ camp and he relates to the politics of identity involved. ‘It’s an odd thing, national identity. When you live in Quebec, you don’t feel Canadian. You’re burdened by this prime minister and the rest of the country doesn’t have the same values that we do. We’re neighbours, that’s all.’

Yet, working internationally, Lepage represents his country as well as his home province — both sent commissioners to his first night — and he’s every bit the cultural export. Unlike most artists, he’s not uncomfortable with that. ‘It’s fine,’ he shrugs. ‘Artists can play a role in the shop window of ideals and the savoir-faire of your country — as long as the country is as you represent it. If you don’t necessarily agree with the policies governing your country’ — Lepage calls Canada’s conservative government ‘retrograde’ — ‘representing your country becomes tough.’

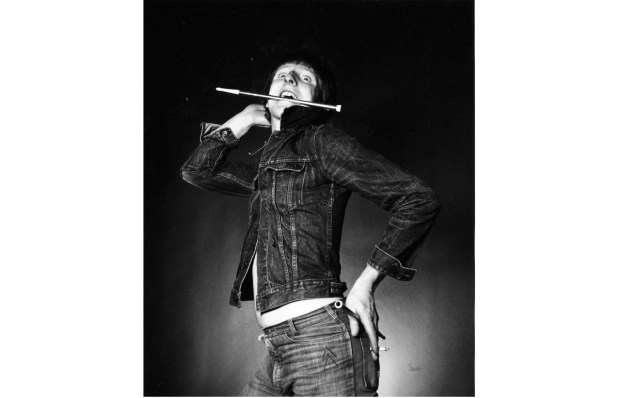

If Lepage’s theatre works internationally, it’s because it is so beguiling to watch. He is a master of transition, sliding between scenes in a way that can collapse time and space. His theatre is mercurial and chimerical. It has to be, he says: ‘If you just tell the thing, then there’s no theatre. You have to use the whole form to communicate. Theatre has come to the rescue of some very dry ideas.’

Composition, then, is a forensic process. ‘You have to study the DNA of a piece of theatre,’ he explains. ‘You have to find out where it connects and how it flows. My theatre is very filmic and, in film, you can switch just two frames and change the whole story.’

Today’s audiences, he believes, are more fluent in storytelling techniques — jump-cuts, flashbacks and the like — but, thanks to the internet, they’re also accustomed to connecting disparate material and ideas quickly. That has the potential to free up theatre and, arguably, it explains Lepage’s return to favour.

He pushes against ‘metronomic’ classical theatre with its beginnings, middles and ends, always looking for something slicker and speedier. ‘Too often the audience are at the end of a play before you are, so they don’t like theatre. They think it’s old and artsy-fartsy. If you’re faster than them, then theatre has a chance of moving into the next century.’ Lepage’s legacy will be getting it there.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

887 runs at the Edinburgh International Festival until 23 August.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in