On the green edge of Clifton Downs, high above the city, there is a sculpture that encapsulates the strange magic of Richard Long. ‘Boyhood Line’ is a long line of rough white stones, placed along the route of a faint, narrow footpath. When Long was a boy, this was where he used to play. There are children playing here today. They pay no attention to Long’s new artwork. Already ‘Boyhood Line’ has melted into the scenery. Half a century since he rolled a snowball across these Downs, and photographed the wobbly line it left behind, it feels as though Long has come home.

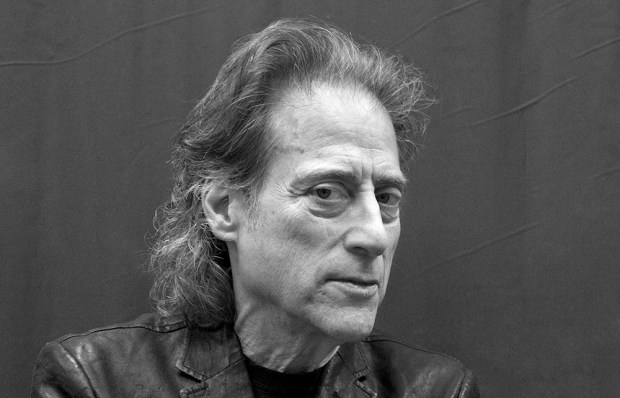

Richard Long was born here, in Bristol, 70 years ago. Since the mid-Sixties he’s been making sculptures all around the world, from Alaska to Antarctica, but he’s never really left the West Country. He still lives in Bristol, and while many of his journeys have taken him to some of the wildest places on the planet, lots of others have started from his front door.

‘Boyhood Line’ is the latest of these local works. It’s part of a new show called Time and Space at Bristol’s Arnolfini Gallery, in the harbour down below. There are two other new artworks in this exhibition — one made from Cornish slate, another with mud from the River Avon — but many of the works in Time and Space were made a long time ago. Yet it doesn’t feel quite right to call this show a retrospective. Long’s work is so timeless that it hardly seems to matter whether he made it yesterday or 50 years ago.

Unlike a lot of artists, Richard Long seemed to start out fully formed. He knew what he wanted to say, and how to say it, right from the beginning. He was still at Saint Martin’s when he made his first big statement. ‘A Line Made by Walking’ (1967) saw Long pace up and down a patch of grass until a silvery line appeared: ‘My intention was to make a new art which was also a new way of walking: walking as art.’

Recognition came quickly — solo shows in Paris, Milan, New York and Düsseldorf within a year of leaving college — yet early success did not spoil him. His work was so elemental, neither fame nor money could affect it. He’s ploughed the same furrow ever since, indifferent to artistic trends or technological innovations. ‘I’ve kept my own way from the Sixties to now,’ he says, on a visit to Arnolfini to unveil this new show. ‘Fashions in art come and go.’ He’s never used a digital map. ‘I wouldn’t have a clue,’ he admits. ‘I think there’s a lot to be said for a compass.’ Once regarded as avant-garde, today he almost seems conservative — a constant lodestar in a changing world.

Walking has always been utterly central to Long’s work. Sometimes, the walk itself is the entire artwork — a short factual record the only souvenir. Even when he stops en route to make a stone circle, or take a photograph, these mementoes seem incidental. It’s art that lives in the imagination: conceptualism, but a very English conceptualism. A quiet, humble, practical riposte to the shoutiness of America’s ideas men. He also makes you want to put on your walking boots and have a go yourself.

Of course there’s a bit more to it than that, as anyone who’s tried to make a stone circle or been on a long walk can confirm. Long’s adventures are often of Olympian proportions, solitary expeditions across deserts — hot and cold: 11 days in Bolivia; three weeks in Nepal…. ‘A lot of my work is based on what’s easiest and most practical,’ he says. He could have fooled me. Even his British hikes can be pretty arduous. Two years ago, he walked 240 miles in eight days, from Cornwall to Oxfordshire — not bad going for an OAP. Remarkably, his only injury (so far) has been a broken ankle, in the Cairngorms eight years ago. He made an artwork out of it, a photo of a snowy ridge called ‘Lull Before a Storm, Pride Before a Fall’.

He’s had one-man shows at the world’s greatest galleries (Tate, MoMA, the Pompidou, the Guggenheim…) but even if he’d remained unknown, an anonymous outsider, you know he’d still be walking, and making art along the way.

The nicest thing about his art is its lack of vanity. Its focus is the landscape and, eventually, the landscape will destroy it. ‘I use the land without the need of ownership,’ he wrote, ten years ago. ‘I use the world as I find it.’ He accepts his outdoor work is bound to change, then disappear. At its finest, his art revels in a childlike sense of wonder. One of his works, ‘Red Walk’, was simply a walk in search of red things, starting with the Japanese maple in his garden, finishing with the red cliffs of Dawlish, chancing upon a red plastic shoe, a red muckspreader and a red sunset along the way.

‘I was always an artist, even when I was two years old,’ says Long. ‘I don’t have any choice — that’s the only thing I can do.’ At infant school, his enlightened headmistress gave him his own easel, and granted him permission to miss morning service so he could paint instead. During his final term at the local comprehensive, he was allowed to paint a massive mural in the school dining-room, without any supervision. Sadly, his alma mater has been demolished, along with his 45-foot mural — yet another of his artworks that’s been swept away by the tide of time.

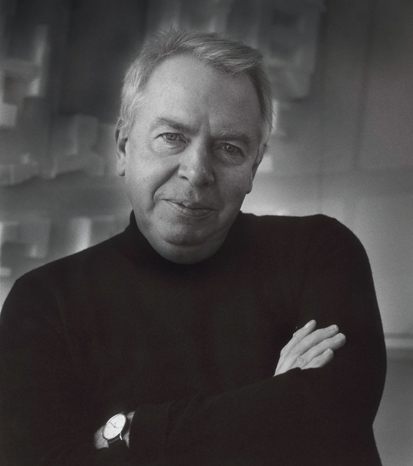

Does walking feel different now, compared with when he started out? I ask him. No, not really, he replies. ‘The experience of walking probably hasn’t changed at all.’ Not many 70-year-olds could make that boast, but when he says so, you believe him. Fifty years of hiking have clearly done wonders for his physique. He has the lean frame and agile gait of an athlete half his age — there isn’t an ounce of fat on him. Tough, canny and ascetic, with the fierce stare of a man who’s spent a lifetime gazing at faraway horizons, he seems more like a prophet than an artist, which is fitting, in a way. There’s always been an element of pilgrimage about his retreats into the wilderness. There’s always been something deeply religious about his art.

I hang around at the end of the press conference, and grab a (very) quick one-to-one. Long gives me only a few minutes, but it’s worth the wait. We stand in front of ‘Dusty to Muddy to Windy’, ‘a walk of 191 miles in five days from Bristol to Truro’. Amid its matter-of-fact descriptions are fragments of pure poetry: ‘Watching buzzards across the Black Down Hills, into Devon followed by a dog, clattering hooves on the road…’ It reminds me of a walk I did with my son, along the Thames, from Woolwich to Henley. Looking at Long’s artworks, that distant memory suddenly becomes very vivid. It makes me want to call my son and ask him to do that walk again.

Is there something special about walking, I ask, even without making any art about it? For the first time, Long’s eyes light up and his voice acquires a richer tone. ‘Oh yeah!’ he says, emphatically. ‘It’s good for the soul — it’s a good way to be in the world.’ And then he’s gone and I’m left alone with his words upon these walls, words that will outlive him, and the rest of us, for as long as people keep on walking. ‘Walking is universal,’ reads his statement at the start of this exhibition. ‘We walked out of Africa for the first time as humans, on foot.’ It takes an uncommon sort of artist to transform those journeys into art.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Richard Long: Time and Space’ is at Arnolfini, Bristol, until 15 November, admission free.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in