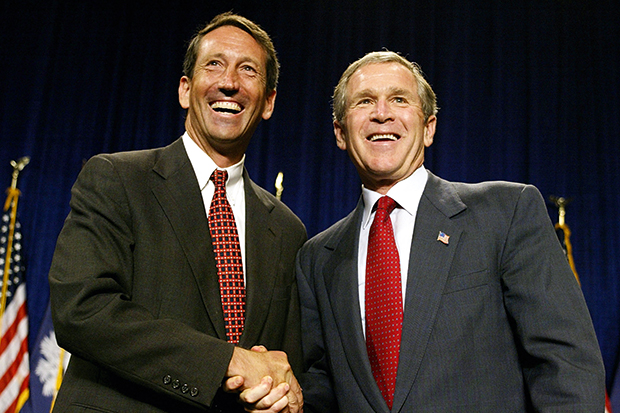

In June 2009, the good people of South Carolina lost Mark Sanford, their governor. Per his instructions, his staff told the press that he was ‘hiking the Appalachian trail’. When he turned up six days later at an airport in Atlanta, Georgia, he said that he had scratched the hike in favour of something more ‘exotic’.

When it became clear that ‘exotic’ meant visiting his 43-year-old polyglot divorcée mistress in Argentina, things got bad. ‘I will be able to die knowing that I found my soulmate,’ he told the Associated Press, sobbing.

Barton Swaim has written a memoir of his three years working as a speechwriter for Sanford, who is now a congressman. The ‘governor’, as he is referred to throughout, is boorish, arrogant and penny-pinching. He stuffs boiled shrimp and boiled eggs in his jacket at parties and gives old T-shirts and ‘jars of shoe polish wrapped in cellophane’ as Christmas gifts. He insists that ‘Aleve’ — as in the pain reliever — is a verb when spelled with two ls. He repeats words (‘again’) and even noises (‘aahh’, ‘wwwww’) whenever he thinks someone else is about to speak. After the news about his infidelity has come out, Sanford compares his plight to Viktor Frankl’s in Auschwitz: ‘It’s incredible to me how you can find beauty, how you can find reasons to keep going, in the most appalling circumstances.’ Among those present, one woman thinks of responding; instead she weeps.

Swaim, a regular on the TLS’s ‘Freelance’ column and the author of a fine book about the history of Scottish periodicals, writes here in a breezy, elliptical manner, letting his material work for him.

There is a lot of it. Nearly every page of this book is wet with the tears of a pedant. At their first meeting, Sanford interrupts Swaim to ask whether it is appropriate to begin a sentence with a preposition. Swaim suggests that he must mean a conjunction, in which case it is a silly non-rule that no good writer has ever observed. Sanford is unconvinced: ‘There’s a rule against beginning a sentence with a prepositions [sic] — conjunctions, whatever — and you can’t break rules.’ Determined to keep the boss happy, Swaim dutifully tries to remove ‘yet’ from a speech a few weeks later, only to be rebuffed by a colleague who assures him that Sanford ‘doesn’t know “yet” is a conjunction’.

Despite, or perhaps because of, his large fortune, Sanford is desperate for the linguistic common touch; he scoffs at a draft of a newspaper article in which Swaim uses the phrase ‘the extent to which’. When Swaim sees the piece later, its first two sentences read

As the old saying goes, the first step to getting out of a hole is to quit digging. I think this certainly applies to the mountain of debt facing our country.

‘Is it a hole, or is it a mountain?’ Swaim asks a colleague. Later, fearful of being fired for writing too well, he makes a list of Sanford’s favourite clichés; using this as a template he is able to put together speeches that are well received.

Swaim is insightful not only about Sanford but about the nature of modern political communications, in which a good written statement is one that ‘said something without saying anything’. This is not, he suggests, mere cynicism. Politicians are expected to have an endless number of digestible opinions; their success depends upon supreme self-confidence and everything odious that comes with it.

Although it left me feeling slightly dubious about democracy, I have no trouble calling The Speechwriter, with its gloomy reflections and wonderfully vivid character sketches, the best American political memoir written in my lifetime.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in