Gstaad

Last week I dreamt of a girl I met in the summer of 1953, in Greece. I had never dreamt of her before. We spent two months together and had a platonic love affair. She got married and died soon after. She was older than me, but not by much. I had turned 16 that summer and had been to bed with a couple of ‘nice’ girls by then, but the rest had been mostly hookers. Her name was Maria Agapitou, and she was a rare beauty, at least in my inexperienced eyes.

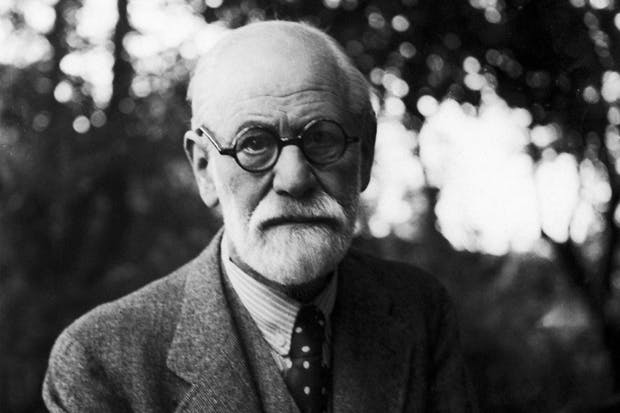

The ghastly but undeniably brainy fraud Sigmund Freud defined love as overvaluing the object but undervaluing reality. Freud was a complex-ridden smartypants who probably never experienced the sudden glow, the chemical effect that random attraction is all about. He was, nevertheless, taken seriously by many, so he’s got a lot to answer for in these psychobabbling times. Mind you, Freud and the summer of ’53 have nothing to do with each other. That time is all about the flickering ecstasy of a long-ago memory, and the impression that a young woman made on a teenager.

An inner voice tells me to beware of nostalgia — after all, I last saw Maria 62 years ago — but at my age the past is richer than the future, so here goes. We met in a park in a northern resort of Athens, where I was sitting on a bench and reading Tender Is the Night. She took the bull by the horns, so to speak, and hinted in perfect English that the book I was reading would inspire me to lead a dissolute life. ‘I sure hope so,’ I answered. That did it. We started to meet every day in that beautiful jasmine-scented park among the pines. She was taller than me by an inch, had light brown curly hair and blue eyes, and would be described as pre-Raphaelite, a term I didn’t know existed back then. We went to the flicks, as we called them, to an outdoor cinema, where she caught me looking at her sideways and told me to look at the screen. I also tried to hold hands right away, but she pulled hers away. Most of the time she wore a black dress, but one day she wore white at a party given by some friend. She knew everyone there, a crowd aged mostly 20 and over. ‘I see you brought your Americanaki,’ said the hostess. (The little American.) No one bothered to speak to me so I proceeded to get very drunk, so drunk in fact that I had to lie down on a sofa near the entrance where I passed out. Later on, I found out that my father and some friends had dropped in and had seen me asleep. The old boy was rather proud, apparently. Go figure, as no one said back then.

We didn’t see each other for some time after that — I didn’t dare go to the park — but then she walked into my life once again as I sat around there pretending to be reading. What I didn’t know then but had more or less figured out was that beauty is founded upon romance and romance is founded on mystery. Maria would repulse every pass I made. I would say nothing but would hide for a couple of days hoping against hope that my disappearance would make her change her mind, and then the saga would start all over again. Whether she was a prude, a virgin or an experienced woman who liked to torture I never found out. She treated me like both a child and a lover. Young love can be as traumatic as hell, and I was really traumatised. All I did was think about her. I stopped playing tennis, stopped going to the brothels, stopped seeing my friends. My mother noticed I wasn’t eating but blamed it on Greek cuisine.

That love is a disease we all know and agree upon. Young love, of course, is ten times worse. As the summer drew to a close I became more and more desperate. She also seemed upset. We kept meeting and then feeling desperate. There’s nothing like unrequited love to drive one over the top. But was it unrequited? Sixty-two years later I can remember perfectly the look she used to give me. She also spoke beautifully, in a language I wasn’t used to, using torrents of adjectives when talking about literature, and in sensuous phrases that left me thinking about them long after she and I had parted. Looking back, there was nothing of the Emma Bovary about her, nothing needy or wanting. She spoke in a cool, almost lyrical tone, in what to me sounded like superbly crafted sentences. The end was too painful to recall. One moment I was talking to her and shyly trying to avoid her gaze, the next I was on an airplane flying back to school and prison-like conditions. I did not take her address or write to her from prison, but over Christmas I remember my mother telling me that she had got married. Then, the following spring, I heard that she had died.

Was it true that she had got married, and then died? I should have realised what a moral coward I was because I never wanted to find out. Was it my mother’s way of making me forget about her? Could she still be alive? Basically, I don’t want to know. But I did dream about her last week. And it upset me.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in