It’s hard to turn on the television nowadays without being shown a robot. It might be looking like a grasshopper doing something terribly important, such as helping a surgeon with an operation, or just be a cute little metal humanoid designed to make schoolchildren more interested in their studies. One robot I saw on TV the other day was disguised as a cuddly white seal pup that was feigning pleasure at being stroked on a woman’s lap in an old people’s home. It seemed to make her happy without biting or scratching or doing any of the other unpleasant things that live animals are prone to.

Robots clearly have their uses, then. But why is so much airtime now devoted to them? It seems to be the fault of Professor Stephen Hawking who, at the beginning of the year, sounded a fearsome alarm. ‘The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race,’ he said. This seemed rather a wild statement. Even if we made robots that turned out to be cleverer than ourselves, why should that necessarily mean our extinction? Couldn’t we achieve peaceful coexistence? Wouldn’t they be needing domestic servants?

Nevertheless, Hawking’s fears have been echoed by others. The Canadian science-fiction writer Robert J. Sawyer urges ‘prudence’ if we don’t want the machines we are building now to become ‘our new robot overlords’. ‘By the point when you sit down in front of your computer and your computer says, “Good morning, I’m in charge now,” it’s too late,’ he says.

Too late for what, exactly? It’s not clear to me. But what does seem clear already is that robots are going to put more and more of us out of work. In Milton Keynes, only a few miles from where I am writing this, there will soon be experimental driverless taxis ferrying people around town and negotiating its famous roundabouts.

It may not be many years before there are no taxi-drivers left in Milton Keynes at all, for taxi-driving is one of the jobs that the experts predict could be done better by robots, who would almost certainly be quieter and more polite. It is one of the 35 per cent of current jobs in the United Kingdom that are considered at high risk of being computerised during the next 20 years.

If you go on the BBC News website you will find an assessment of how susceptible your job is to automation. This is according to calculations by two Oxford academics, Michael Osborne and Carl Frey, who have based them on the nine ‘key skills’ that they think jobs require: social perceptiveness, negotiation, persuasion, assisting and caring for others, originality, fine arts, finger dexterity, manual dexterity, and the need to work in a cramped workspace. A very peculiar selection, if you ask me.

Anyway, the likeliest jobs to be computerised are fairly predictable, with ‘telephone salesperson’ (the one that tops the list with a 99 per cent chance of being automated) appearing to be taken by a robot already. But naturally one is most interested in one’s own position. So I ploughed down the endless list of jobs until I reached ‘Journalists, Newspaper and Periodical Editors’.

The prospects are good. We have only an eight per cent chance of being replaced by robots in the next 20 years, the same as a ‘childminder’ or a ‘bar manager’. This must be because people like us have to excel in the skills that robots are, at least so far, rather poor at: social perceptiveness, negotiation, persuasion etc. Robots are not good at empathy. Even so, they already write lots of sports stories and company reports, so we shouldn’t be complacent.

But why should a ‘senior police officer’ (at 17 per cent) be more than twice as likely to be ‘automated’ as the editor of The Spectator? You’d think he might need to be capable of empathy, too. And the more one thinks about it, the more absurd these threat rankings seem. In envisaging a robot taking over as editor of this journal, for example, you would have to imagine it occasionally having to fire other robots, which might then seek a ruling for unfair dismissal before a presiding robot at an industrial tribunal. This is a difficult scenario to envisage.

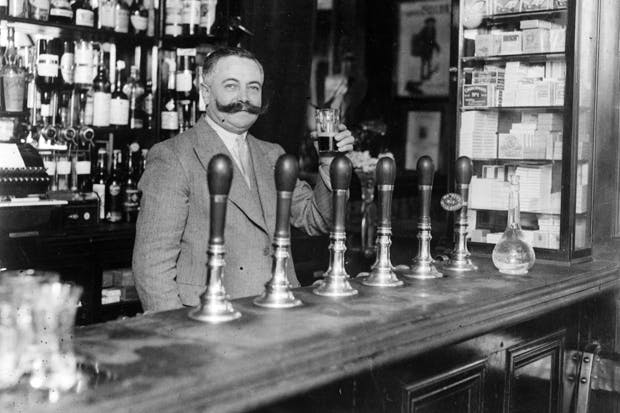

It makes superficial sense that artists, architects and musicians (not to mention dentists) should be considered even less likely to be replaced by robots than journalists, but why should publican (on 0.4 per cent) be the least threatened job of all? It shouldn’t take long to teach a robot to say ‘Time, gentlemen, please!’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in