London may cry foul over Hamlet’s misplaced to-be-ing and not-to-be-ing but Edinburgh is in raptures over a Magic Flute which ditches its spoken dialogue entirely. Directed by Barrie Kosky and Suzanne Andrade, and first seen a couple of years ago on Kosky’s adopted home turf at the Berlin Comic Opera, the production turns Mozart and Schikaneder’s beloved singspiel into a sing-stumm, in which silent-movie captions and moon-faced gazes replace the original spiel, underscored by fortepiano improvisations with a spot of Chinese opera thrown in for good measure.

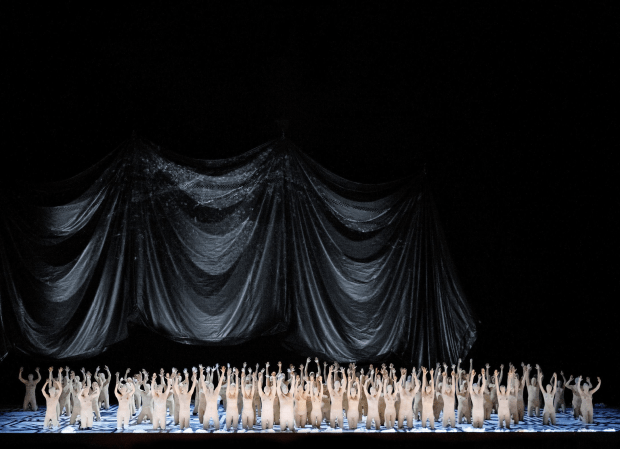

Not your usual night at the opera, then, but it certainly drove the Festival Theatre audience wild. The visual style mixes up Buster Keaton, F.W. Murnau and Monty Python, with the action dominated by slick animation sequences projected on a drop screen in which cut-outs revolve to reveal the live singers on promontories of varying precariousness. The opera’s first number finds Tamino’s torso swaying atop projected running legs. The character thus seen fleeing towards us, hotly pursued through a geometric jungle by a cartoon dragon. By the time the dragon’s fire is extinguished by the three ladies’ nonchalant exhalations of cigarette smoke, the sense of who’s who and what’s what is already well established: Pamina is Louise Brooks; or, rather, all women are, except the Queen of the Night, a black widow, and Papagena, a stray chorus girl from the Rue Pigalle. Monostratos is Nosferatu, the three boys are butterflies, Sarastro is Brunel, obviously, and Papageno has a black cat and magic bells that dance the can-can.

The animation is the work of Andrade’s creative partner Paul Barritt and is cleverly integrated and unremittingly charming, unveiling a virtual vaudevillian world in which the opera’s childish allegorising, for once, makes perfect cartoonish sense. Even the magic of the flute itself — a little Tinkerbell with a black bob and not much else — is palpable. Indeed, it’s a shame she doesn’t dance more on the musicians and singers themselves because they could use the help. The problems begin with the overture, which Kristina Poska (a female conductor, and left-handed to boot: hurrah!) directs as if merely checking the players know their parts (they do). There’s a strong sense, though, that most of the trouble derives from the constraints set by the multimedia infrastructure. Poska, for example, is rarely free to wait for the whoopers and clappers to finish plying their trade: she must press on or lose contact with the projections. Singers, too, who rely on a certain amount of movement and gesture to animate their voices, are here often pinned to the backdrop or held in still poses so that the projectionist can have his way with them. Allan Clayton’s Tamino suffers the most in this respect, sounding uncertain and frequently rather lifeless, but Maureen McKay’s Pamina and Dominik Köninger’s Papageno are often constricted, though both improved in the second act. Tying up Olga Pudova’s Queen of the Night, by contrast, unleashes some magnificently controlled coloratura, which goes some way to compensate for the lustre lacking from most of the music. But since music increasingly plays an auxiliary role in people’s idea of opera, then perhaps it doesn’t matter so much.

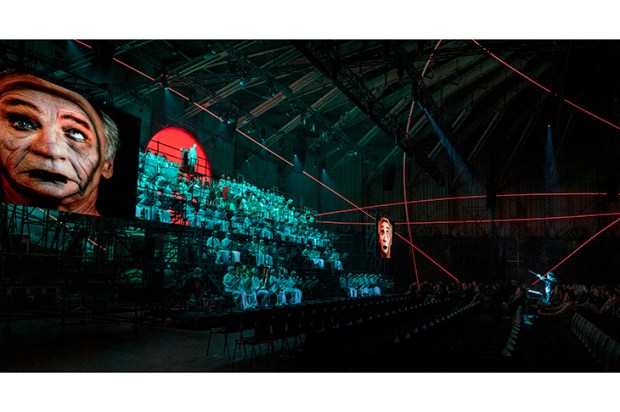

The projectionist’s art makes further strides into the fabric of theatrical representation across town at the Lyceum, where writer David Greig and director Graham Eatough have had the heroically misguided idea to adapt Alasdair Gray’s epic of idiosyncratic tragicomic gothic dystopian sci-fi realism, Lanark, for the stage. Like The Magic Flute, Gray’s 1981 novel uses matrimonial happiness as a synecdoche for social and cosmic balance. In Gray’s case, however, his hero’s chronic inability to find love mirrors a world in which authentic human feeling is being progressively squeezed out of existence by corporate capitalism — in the factories of postwar Glasgow, or its dystopian alter-ego, Unthank, in which the diseased remnants of humanity are kept alive for fuel and food by The Institute, deep underground.

Prized for its Glaswegian wit and cosmic poignancy, Gray’s novel is widely revered, particularly by those who persevered through all 600 of its strange and dense pages. And there is a sense in this adaptation, ingenious as it is, that these survivors are really the target audience: with the narrative squeezed into three and a half hours (a long time in the theatre but a short time in Gray’s meticulously detailed fictional worlds), the action often feels animated more by readerly reminiscence than live storytelling.

Thanks to video artist Simon Wainwright and lighting designer Nigel Edwards, the frequent scene changes keep pace, and the relatively simple stage apparatus acquires a powerful illustrative force. It also rains constantly — at least in the dystopian outer acts. The central act, in which The Institute’s Oracle reconstructs Lanark’s former existence as gawky Glaswegian art student Duncan Thaw, is entirely tech- and prop-free save for a bare scaffold. Instead, the details of Thaw’s childhood and adolescence are brought to life by the combined talents of the company’s ten actors, all identically dressed in braced beige cords and desert boots (a look adapted from Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach). Led by Sandy Grierson, who conveys Lanark’s blurry-minded determination with true brilliance, it’s really the energy and resourcefulness of the actors which holds the play’s precarious dramatic edifice together, with amusing and frequently moving results.

The music — slabs of mangled jazz and retro electronica — is rather dismal, though, and my ears relied for sustenance largely on treasured memories of the morning’s superb Queen’s Hall concert, featuring the Zehetmair Quartet playing early and late Haydn together with Hindemith’s Fifth Quartet. A heaving, pulsating mass of a work, which echoes Haydn’s more politely achieved integration of popular and learned styles, the Hindemith is an under-appreciated masterpiece, its bold, proto-Shostakovichian rhythms and unusual expressive depth beautifully caught by the players.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in