According to this wonderfully thought-provoking book, human attachment to plants was much more evident in the 19th century than it is now. In those days people showed genuine wonder at their ‘strange existences and unquantifiable powers’, especially the British, who fashioned the most ambitious glass building of the age —the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park — drawing on the weird architecture of the amazonica lily as a blueprint.

Richard Mabey suggests that these are more prosaic times, where trees are invariably seen as primary producers, economic heavy-lifters or practical oxygen-supply operatives, or merely as a vegetative background to the planet’s real agents: ourselves and other animals. In short the green stuff is underestimated and we need to rediscover what he calls the ‘intentions, inventiveness and individualities’ of plants.

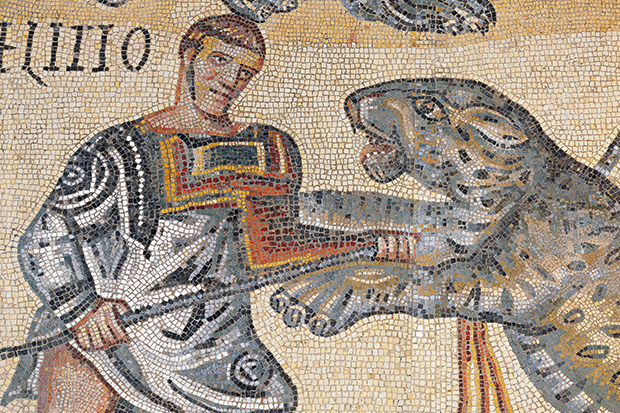

Perhaps, before dismissing our own times, we should recall a figure like Balin who, in the winter of 1996, lived up an old oak in protest against the proposed bypass around the then silently wooded outskirts of Newbury. For a fortnight he clambered about its limbs, reading Cervantes, hoping to save just one of 20,000 trees that were eventually felled, and supplying copious copy for national newspapers as they charted his primate’s progress. In the end, however, the bailiffs chainsawed his tree down and beat Balin with iron straps about the head for making them wait.

If there are people who still cling passionately to the importance of trees then it is partly because of Mabey’s lifelong devotion to this theme. And of all his 30-plus books this is surely among his finest, an eclectic world-roaming collection of stories that evoke the extraordinary ways of the vegetable world.

He unravels the complex symbolism of Wordsworth’s daffodils, gives us a potted history of maize and its 9,000-year-long cultivation. He pauses in Lincolnshire to pluck one of Newton’s apples and branches out in China to explore the New Age cure-all ginseng. He also relishes the innuendos linked to that role-reversing wonder the Venus-flytrap, a plant that catches and eats insects. Apparently the English and scientific names are a pun on the vagina dentata.

My favourite chapters are those where the author has first-hand encounters with the plants under discussion. His stock of memories allows him to lace colour, intimacy and emotional texture around the scaffold of hard facts. A good example is his account of yew trees that have a recurrent presence in places of Christian worship.

Quite why yews have this church-going habit remains a mystery, but the most persistent myths include the idea that the trees’ toxic foliage kept the cattle off the graveyard, or that they were planted to supply longbows to medieval archers. Mabey scotches both rumours but can find no definitive explanation.

What we do know is that some yews are not only older than the buildings they keep company, they are older than Christianity itself. One of the most famous is the Fortingall yew in a Perthshire village of the same name, which was around when Stonehenge was a youngster. This is impressive enough, but what about the cluster of clonal aspen trees in a Utah forest that the author also mentions? These may well be 80,000 years old.

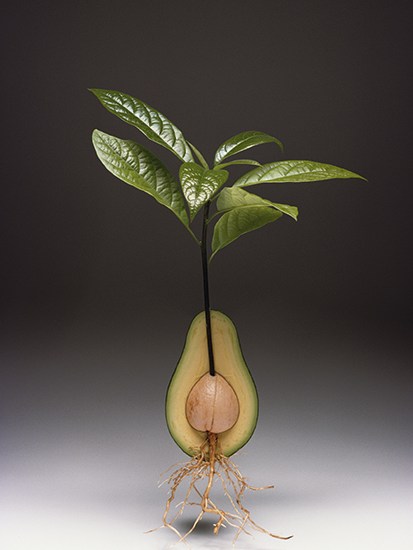

Mabey stresses that plants are not merely the mainstay of life, through the three-billion-year old process of photosynthesis; they transcend even this fundamental role and have helped shape the very fabric of the human imagination. Our language and the ways in which we structure our thoughts owe something to plants. When Darwin, for example, tried to illuminate the processes of evolution that absorbed his entire career, the most apposite metaphor he could conjure was what he called ‘the great Tree of Life’.

In a book that looks back over more than 60 years it is inevitable that there is a melancholy cadence to some of the tales. Among the most moving is Mabey’s affectionate portrait of Tony Evans, with whom he worked on an illustrated flora. Evans died prematurely in 1992, but was one of Britain’s most famous still-life photographers and legendary for his patience, once taking 11 days on Morecambe’s shoreline to capture cockles emerging from their shells.

Mabey reveals that his own lifelong pursuit of plants began by the sea, with samphire. It is noted as a kind of seaside asparagus, but what captivated the author of Food for Free was not just its crunchy texture and iodine flavours. Through its tenacious hold on the underlying substrate, samphire slowly turns the intertidal mud at its roots into dry land, where it cannot thrive. To Mabey the young naturalist this seemed to subvert the very notion of Darwinian fitness, whose central axiom is that a species’ adaptations maximise its own survival. Yet there was also something else in samphire that appealed to Mabey the late Romantic. Here was no passive greenery, but a plant with agency and a self-willed agenda. He has been pursuing samphire ever since, and we are all the richer.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £17 Tel: 08430 600033. Mark Cocker is a naturalist and the author of A Tiger in the Sand and Crow Country.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in