There are some things the French do better than everyone else. Cheese, military defeats and extra-marital affairs are a given, but what about opera? English Touring Opera’s autumn tour sets out a tasting plate of the nation’s Romantic finest, hoping to persuade audiences that there’s more to France than just Carmen. Debussy’s delicate tragedy Pelléas et Mélisande sits between the fragrant melodies of Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann and the Armagnac-soaked passions of Massenet’s Werther. It’s a typically wide-ranging programme from this small company, but one whose compromises inevitably equal its ambitions.

While the ambition is spread pretty evenly across the three works, the lion’s share of the compromise falls to Werther — Massenet’s heady adaptation of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther. It’s a work that suffers from the classic epistolary-novel syndrome of too much emotion hanging off too little plot.

With a full orchestra to support its dramatic fragility, the opera musters a sub-Wagnerian impetus, music emerging freely from feeling without the artifice of set-piece arias and ensembles. By stripping it of its harmonic soft furnishings and cramming it into the musical bedsit of just a quartet of instruments (violin, cello, clarinet and piano), ETO and director Oliver Platt have reduced a domestic tragedy to a kitchen-sink squabble.

But John Osborne this is not, and neither Matthias Klaes’s programme note nor Oliver Townsend’s relentlessly realist 1950s set can make it so. Retired magistrate Le Bailli (Michael Druiett) and his family live in implausible poverty in an unchanging domestic interior that must, at whim, also serve for street scenes (it’s all to do with where characters enter from). It’s about as clear in performance as it is in explanation, and is further complicated by the band performing on stage (somewhere between the sink and the Christmas tree), obscuring the English text the lack of surtitles makes so essential.

An odd decision to use Massenet’s own arrangement, which recasts Werther as a baritone rather than a tenor, adds to the prevailing gloom, denying us the music’s giddy, passionate heights without really offering much in their place. Ed Ballard does his best with what little he’s given, but a pair of Schubert specs and a side-parting do nothing to champion his romantic cause against Simon Wallfisch’s swaggering Albert — a GI with a sexy smoking habit and a much brighter, more projected baritone.

Carolyn Dobbin’s Charlotte is warmly sung but too matronly to make anything but awkwardness of Werther’s fumbling seductions (would this bookish lover really grope his idolised and idealised beloved quite so vigorously?), leaving Lauren Zolezzi’s Sophie (bell-clear and beautifully sung) as the sole point of laughter and light. Young Werther certainly had his sorrows, but I doubt even Goethe intended them to be as unremitting as this.

Relief is at hand, however, in the form of James Bonas’s The Tales of Hoffmann. The steel-capped comedy of Offenbach’s final, phantasmagorical opera is a tricky ask, demanding both gleeful delight and a real sense of danger if it is to come off. Cutting this unwieldy score back to its absolute shortest (the show runs at under three hours), Bonas still manages to retain both, while a superb young cast brings all possible energy to this transgressive romp of a production.

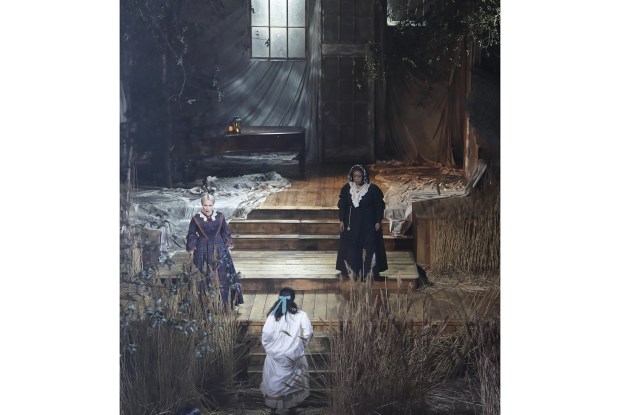

Bonas takes his cue from Offenbach’s score — a magpie-nest of musical quotations — and crowds his 1920s, silent-movie setting with visual references. Dr Miracle (Warwick Fyfe) becomes a long-fingered, cape-tossing Nosferatu, while Adam Tunnicliffe’s Spalanzani channels Metropolis’s mad inventor Rotwang. The poet Hoffmann’s beloved Stella (played in each of her incarnations by the soprano Ilona Domnich) is, of course, a movie star. Her three personas — child-innocent, artist, whore — come to the fore in starring roles in three different films, each an atmospheric miniature thanks to Townsend’s nimble designs.

Sam Furness’s Hoffmann is tireless. Flinging himself with Romantic rapture at Offenbach’s endless supply of melodies, this exciting young tenor, by turns deftly comic (‘Kleinzach’) and sustainedly lyrical (‘C’est une chanson d’amour’), proves himself a vocal chameleon to match his shifting lover. Fyfe makes a fine nemesis, with a wild top to the voice that lends real and growing menace to the Coppelius/Miracle/Dappertutto trio of villains, playing off Adam Tunnicliffe’s lovely open tenor (Spalanzani, Pitichinaccio) and Louise Mott’s knowing Nicklausse/Muse. Only Domnich doesn’t quite master the vocal reinvention of her many roles — a little too effortful as the automaton Olympia, though finding an appealing fragility for Antonia.

With conductor Philip Sunderland’s orchestra (a positively Straussian 11 players compared with Werther’s quartet) restored to its rightful place in the pit, there’s a sense that all’s right with ETO’s operatic world again here, of ambition once again outpacing limited resources. Such is the wonder of this Little Opera Company That Could that you can catch Hoffmann and Pelléas (and yes, even Werther if you’re determined) anywhere in the UK from Buxton to Exeter over the next three weeks. When was the last time anyone could say that of three such challenging works?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in