Listen to Me Marlon is a documentary portrait of Marlon Brando that has him burbling into your ear for 102 minutes, but if you have to have someone burbling in your ear for 102 minutes — and there is no law saying it’s obligatory — you could do a lot worse.

This isn’t one of your regular documentaries. There are no talking heads, and it’s not blah-blah-blah and then he did this and then he did that and then his BMI got ridiculous, and so on. Instead, it is based on the hundreds of hours of personal audio tapes Brando made in his lifetime, which haven’t been heard until now, and which were uncovered by film-maker Stevan Riley, who wrote, directed and edited. (According to Riley, Brando preferred to speak his thoughts rather than write them down in diary form as he was severely dyslexic.) So, rather than a biography, it’s more a journey into Brando’s troubled mind (his own heart of darkness?) as he reflects, rages, despairs, questions, casts himself as victim (always), rejects the PR game — ‘I did not want to lie at the feet of the American public and let them enter my soul’ — and attempts to self-soothe.

Some of the cassette tapes are labelled ‘self-hypnosis’ and have Marlon encouraging Marlon to ‘let go, let go’ and stop stuffing his face quite so much. ‘Listen to me, Marlon,’ he says. ‘Think of all the good things you like to eat, like apple pie and ice-cream and brownies and milk. But you must not eat them quite so often.’ Marlon talks to himself about himself. Whatever else, I don’t think you could ever say Marlon wasn’t sufficiently interested in Marlon.

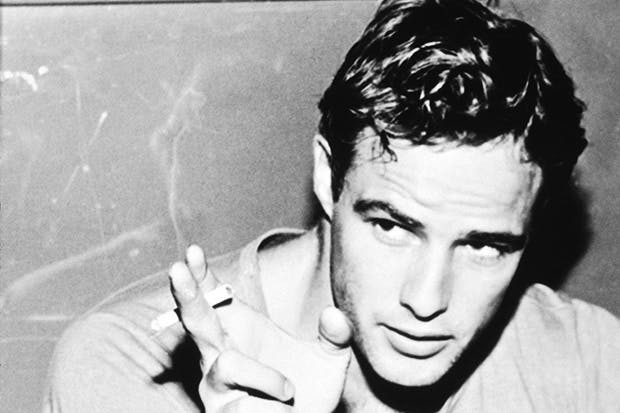

His voice is played over home movies, photographs, vintage television footage, film clips. It is not chronological, in the same way that thoughts are not chronological, are always slipping between the present and the past, but it covers most of the ground. There’s Brando remembering his childhood, as blighted by a mother who was the town drunk and a father who was cold and violent. There’s Brando as a young man, with those electrifying good looks, and delivering the electrifying performances that cut through decades of screen mannerisms and changed film acting for ever. (That said, he describes his performance in On the Waterfront as ‘embarrassing’.)

We see him playing the PR game in the days he did play the PR game; when he would hit on female journalists (so flirty!) and would appear alongside his father for the TV cameras, affecting a friendliness that never existed. ‘Hypocrite’, we hear him hiss.

Riley uses the images either to back up what Brando is saying or as a counterpoint. Or he makes psychoanalytic associations, as when we cut from Brando talking about his father, who seems to have much to answer for — ‘he used to slap me around, for no good reason’ — to that moment in A Streetcar Named Desire when his Stanley Kowalski pounds the kitchen table and Vivien Leigh’s Blanche DuBois all but jumps out of her skin. (‘I hate that kind of a guy,’ he says of Kowalski. ‘I absolutely hate that person.’)

It is genuinely fascinating to hear him talk about the work. He describes having to audition for The Godfather as ‘demeaning’ but ‘I needed a part at that time.’ Bertolucci, he says, drew such a truthful performance from him in Last Tango in Paris that he felt violated, as if something had been stolen from him. And he rails against Francis Ford Coppola, who ‘dumped on me’ after Apocalypse Now (by saying he’d arrived on set without knowing his lines and was spectacularly obese) whereas, in fact, he rewrote that film, from top to bottom, ‘and I saved it’. He is often delusional as well as self-pitying.

Although the film was made with the approval of Brando’s estate, it does not shrink from the womanising, the lurid personal tragedies (especially regarding his own children: one was convicted of murder, one committed suicide) and the tragic final years, when he was fat, mumbled, refused Oscars and had to have his lines fed to him through an earpiece. (I blame his father.) Bringing it all together is a triumph of editing, although Riley does employ some annoying tics, as when he fills any downtime with visuals of billowing sheer curtains or wind chimes, and as when he employs a disembodied Brando head, which the actor himself had made from digital scans in the 1980s, and which is just distractingly creepy.

Do we understand Brando better by the end? Not really, but his unfettered thoughts are what matter rather than any destination, and as a portrait of someone searching for the truth about himself and not especially getting anywhere — who ever does? — this feels unusually intimate. It’s burbling at its most compelling. And, like I said, you could do a lot worse.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in