This is my 345th and last monthly column about pop music for The Spectator. I believe I might be the third-longest continuously serving columnist here, after Taki and Peter Phillips. Others have been writing for the magazine for longer, but have occasionally been given time off for good behaviour. You may be astounded to learn that I have not been fired. I, certainly, am astounded. I have been waiting for the tap on the shoulder, or maybe the firm but regretful email, since my first column in May 1987. Eventually I came to realise that the less the editor of the time was interested in my subject, the safer I was. As sheer delight in survival morphed into freakish longevity, I decided it was best to maintain a low profile, to the extent that when the 25th anniversary of the column loomed a couple of years ago, I asked Liz Anderson, legendary arts editor and tireless moral support to any number of anxious columnists, to say nothing to anyone. It’s not that I didn’t want people to make a fuss about it. I’m not that modest. It’s that I didn’t want people to make a fuss about it and then fire me straight afterwards.

This year, though, I have started to feel that I have said almost everything that I have to say on the subject, possibly several times. Once it becomes hard work to write a column, it won’t be long before it becomes hard work to read it. I have also spent a decent chunk of the year in The Spectator’s offices leafing through dusty old binders for a book I am compiling for Christmas 2016, entitled The Spectator Book of Wit, Humour and Mischief. Reading so many wonderful columnists in intense bursts, you see that even the best of them eventually runs out of steam. In my case, I suppose, I could also say it was an age thing, except that it wouldn’t be true. I was 27 when I started writing this, and I am 55 now, but I was an unusually crabbed, creaky and ill-tempered 27-year-old, who already felt left behind by the way pop music was developing, and preferred the music of his own teenage years, as almost everyone does. This hasn’t changed much. I still think hip-hop is a waste of ears. Grunge was spectacularly uninteresting. Of Britpop I now listen to only Blur and Supergrass. And so on.

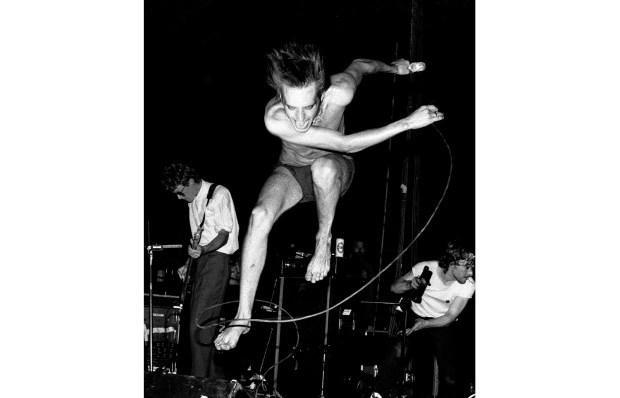

The truth, and the problem for any such columnist, is that there’s far too much music out there for anyone to keep a handle on, and pop follows what I learned this week is called Sturgeon’s Law, after the science-fiction writer Theodore Sturgeon. This states that in every arena of artistic endeavour, 90 per cent of everything produced is crap. All you can do is find the 2 per cent you like and listen to that, which I do with pleasure, every day. But I have always been aware that my 2 per cent is probably not your 2 per cent, and it may not actually be anybody else’s2 per cent. All men are islands, and our taste in music makes us particularly small, isolated islands separated by vast unnavigable stretches of stormy sea. This is why people still love going to gigs: because for one night only, they are surrounded by strangers who love this music as much as they do. Then it’s back home, where everyone tells them to turn that bloody racket down.

Pop’s place in culture has changed drastically during my tenure. When I was growing up and buying NME and Sounds every week, there was no such thing as a pop column in The Spectator, and newspapers ignored the music as though it wasn’t there. Then the baby boomers took over the media, Live Aid happened, Bono started wearing those sunglasses, Sting released an ever more pompous string of jazz-inflected albums no one played more than twice, and it became clear that pop had captured the mainstream. At the time we assumed that this would be a permanent state of affairs, and indeed, Bono is still wearing those sunglasses. But the music has drifted back out of reach and away from people’s lives. Even substantial stars of today, the Sam Smiths, the Lana Del Reys, are listened to only by their core constituencies. How many new songs are there every year that absolutely everyone knows? Half a dozen?

That’s not to say that pop music is ‘over’, as one or two of my friends have been heard to say. They have their Neil Young records and feel that nothing more is necessary. It’s just that pop’s present is unusually burdened by the excellence of its past. Music fashioned long ago for instant gratification has proved to possess extraordinary staying power. Over the years I have met one or two pop performers socially and if I have been drunk enough, I have asked them how it feels to have songs they wrote (in some cases, dashed off) in their youth still being played and loved decades later. And they can’t quite get over it either. How did that happen? I bet even Paul McCartney asks himself that question from time to time.

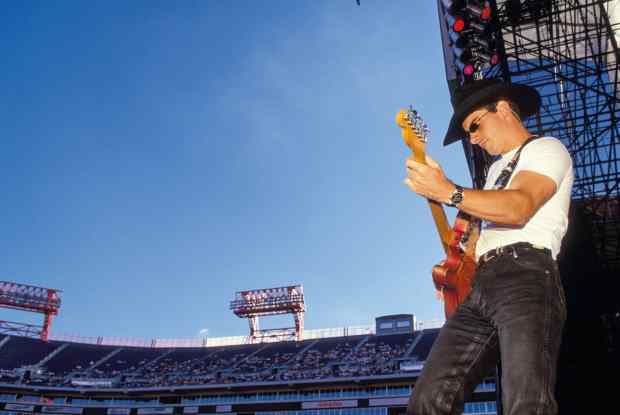

The music industry, delightful behemoth that it remains, squeezes this music dry, of course. I’m not sure there are many manifestations of modern life more dispiriting than the jukebox musical, wherein much- loved hits of yore are attached to a story so thin and ridiculous that only Ben Elton could have written it. At the same time, we shouldn’t be too hard on people who are just trying to make a living. The other day, I met someone else who had grown up and grown old with ABC’s 1982 album The Lexicon Of Love, and we sat and discussed it with wild glints in our eyes. Needless to say, the song we both liked the most was a non-single album track that many people will never have heard of (‘Date Stamp’, in case you are similarly afflicted). Teenage elitism never dies, and as far as we were concerned, neither does that album. Thirty-three years on, The Lexicon Of Love sounds only slightly less than current. ABC’s Martin Fry has never come close to equalling it, but he is still out there, playing it live. It’s one of my favourite albums, and it’s his pension.

So while I will no longer be writing about music, I will still be obsessing about it, and buying too much of it, and being slightly disappointed by most of it. There is a new Squeeze album out shortly. Fingers are crossed. There’s also one by Jeff Lynne, who now calls himself ‘Jeff Lynne’s ELO’ to avoid confusion, although there isn’t any. The Amazon order is already in. That said, I heard a song by Gabrielle Aplin on the radio the other evening and that sounded wonderful, so I might get her new record too. She is only 22. It never stops, and for that, I suppose, we should only be grateful.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Marcus Berkmann’s first Spectator pop column, on Fleetwood Mac and Microdisney, appeared in May 1987.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in