The aggressive character of the famous German sports car, in a sort of sympathetic magic, often transfers itself to owner-drivers. The joke goes: ‘When you get into a Porsche, you feel you want to invade Poland.’ In this fascinating and meticulously researched book, Karl Ludvigsen investigates the genetic spiral that gave Porsche cars the character of weaponry.

All German manufacturers were forced to supply the Third Reich. The BMW-sponsored London Olympics 2012 were held on a site devastated by Luftwaffe planes powered by its engines. But the relationship between Professor Dr Ferdinand Porsche and Hitler, a motor-racing enthusiast, was altogether wider and deeper: the engineer put his design expertise exclusively in the Führer’s service, though only after rejecting an offer from Stalin to become the Soviet Union’s ‘car czar’.

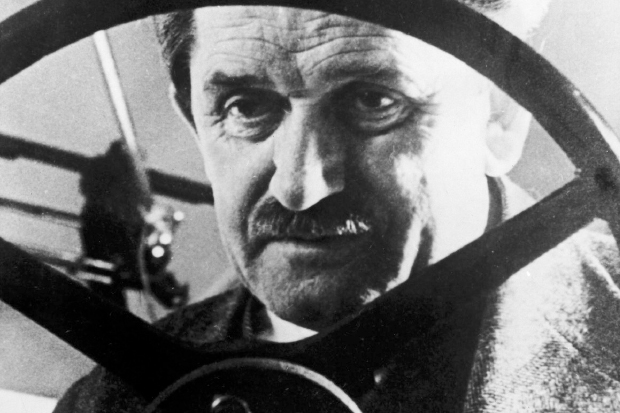

Porsche, technically what we would nowadays call a Czech, was an outstanding representative of the Austro-German engineering tradition. While Britain’s great designer-engineers have been idiosyncratic outsiders, Porsche was at the centre of a vast and disciplined caliphate of industrial alliances. He worked variously for Daimler, Steyr and Mercedes-Benz. His technical genius was considerable: his first car, designed for Lohner, had electric motors integrated into the wheels, a solution that would be remarkable today. But this was 1906.

His first meeting with Hitler was in 1926, when young Adolf introduced himself at the German Grand Prix, a race won by a Porsche-designed Mercedes-Benz. The formal meeting came seven years later. Hitler, to put it no higher, enjoyed technocratic symbolism and saw in Dr Porsche a rich source of it. Porsche became a member of the Nazi party in 1937, but this seems more professional opportunism than political conviction. Still, he returned Hitler’s compliment by designing the astonishing Auto-Union Grand Prix cars. At the same time, to motorise the Volk, he created the Kraft-durch-Freude-Wagen, or ‘Strength-Through-Joy Car’. We now know this as the Volkswagen.

The Volkswagen begat the Wehrmacht’s jeep-like Kubelwagen (Bucket Car) and the amphibious Schwimmwagen (Swimming Car). The Porsche bureau also designed the Panzer tanks. Ludvigsen has marvellous photographs of Hitler’s other educated chum, Albert Speer, test-driving a Panzer while a homburg-hatted Dr Porsche grimly hangs on. At the same time, the Volkswagen factory manufactured a flying bomb which Goebbels branded

Vergeltungswaffe-Ein (‘Revenge Weapon One’). Londoners called the V-1

the Doodlebug.

If Ludvigsen’s fine book has a failing it is that too little is made of the personal relationship between Hitler and Porsche, although not very much is actually known. Like Speer, a sophisticated architect, Porsche claimed a sort of moral neutrality for his engineering profession: he was just doing his job. He was 14 years Hitler’s senior, and the Führer treated him with rare deference, bordering on idolatry. Porsche’s own son, Ferry, the man responsible for the modern sports cars, said: ‘My father was Hitler’s father.’ No one has yet claimed this frank admission for the brand.

At the end of the second world war, Porsche was briefly imprisoned by the Allies but released in time to supervise his son’s 1948 launch of the 356 sports car outside a mountain hut in Gmünd, Carinthia. This was the first car to bear the family name, and (since the company has never much troubled to make public Porsche’s military involvements, which ended only in 1981) the basis of the manufacturer’s current popular reputation. Judging by the old

photographs, Dr Porsche looks a bit wistful. Perhaps a delicate and pretty sportscar seemed frivolous after so many thundering tanks and whistling flying bombs.

Porsche’s success is sensational. It now makes more money than its Volkswagen parent. My office is near the showrooms in Berkeley Square. I am always lost in admiration at the sight of these fine cars. There’s an aesthetic clarity and purposefulness that is deeply attractive. They are perhaps not beautiful, but they are visually fascinating and demand intellectual respect. Just like weapons.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £25 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in