I wonder if Steven Spielberg is having second thoughts about Bridge of Spies in light of the attack on Paris? Spielberg’s latest film —released this week and tipped for Oscar glory — is an espionage thriller set at the height of the Cold War with no immediate relevance to the ‘war’ we find ourselves in today. But it contains a strong liberal message about the importance of observing due process when dealing with enemy combatants and prisoners of war.

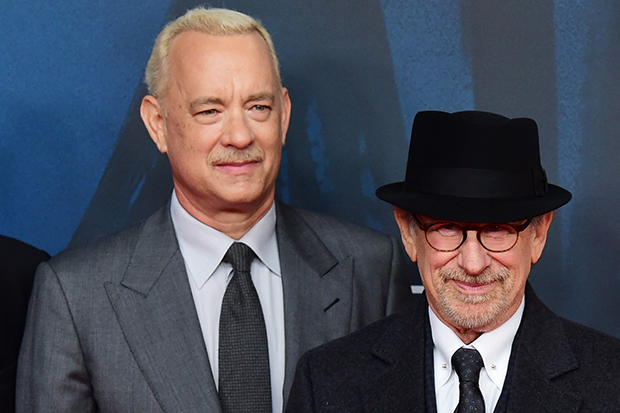

The hero of Bridge of Spies is James Donovan (Tom Hanks), a straight-arrow insurance lawyer who is asked by the American government to defend Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance), a Brooklyn-based artist who’s been caught spying for the Soviets. The reason Donovan’s been asked to do this, explains the man from the New York Bar Association, is that the government wants Abel to be seen to get a fair trial. Donovan has drawn the short straw because he worked as a prosecutor during the Nuremberg trials, although there’s also a suggestion it’s because he’s not a criminal lawyer and won’t be able to mount a robust defence.

Donovan turns out to be not just a capable lawyer, but a stickler for what he calls ‘the rule book’. There’s a pivotal scene after he’s accepted the case when a CIA agent asks him to pass on any information Abel divulges about his spying. Donovan refuses, citing attorney-client privilege, and the agent counters by arguing that the normal rules don’t apply in this case because it concerns national security. At this point Donovan raises himself to his full height and tells the agent that, on the contrary, they do apply. America’s observance of due process, even when the defendant is an enemy of the state, is what makes it a great country. If you abandon that principle, America’s claim to moral superiority goes out the window.

Spielberg and his screenwriters, Joel and Ethan Coen, are clearly making a point about Guantanamo and the use of lethal force to take out high-value targets — at least, that’s my reading of it. Spielberg’s been down this road before in Munich, his 2005 film about Israel’s response to the slaughter of 11 Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olympics. It’s far from being a straightforward revenge thriller. On the contrary, the leader of the Mossad team hunting down the terrorists suffers a crisis of conscience and the film’s final shot, featuring New York’s twin towers, implies that the cycle of violence unleashed by the Olympic massacre led directly to 9/11. Spielberg seemed to say that it would have been better if the leaders of Black September hadn’t been assassinated.

I’m not a fan of Spielberg’s serious films — what his fans think of as ‘thoughtful’ and ‘unsettling’, I’d describe as ‘virtue signalling’ — and prefer his earlier, schlockier work. I like the way Indiana Jones deals with the Nazis — no hand-wringing nonsense there about habeas corpus. The existential threat posed to Western civilisation by the Nazis is a recurring theme in Spielberg’s work, even in his more solemn outings, and at no point does he exhibit the same concern for their rights as he does for those of Communist spies or Palestinian terrorists. In this he suffers from a familiar left-wing double standard. He’s happy to toss judicial niceties out the window when it comes to the Allies’ prosecution of the second world war — he accepts the conventional narrative that it was a straightforward battle between good and evil — but is quick to criticise western governments for employing similar tactics against more recent enemies.

I’m not arguing he was wrong about the Nazis, but that he’s mistaken about the Soviets and Islamists. The depiction of Rudolf Abel in Bridge of Spies is ludicrously sympathetic. He’s portrayed as an honourable man, a man who holds on to his dignity in extremely testing circumstances, and when he praises his defence lawyer for sticking to his principles we’re supposed to treat that as a valuable endorsement. But, really, why should we care what he thinks, given that he’s spying for a regime responsible for the murder of more than 20 million people?

Spielberg’s sympathy for our Islamist enemies is equally misplaced. The struggle we’re engaged in now is every bit as black and white as the second world war and we should no more fight with one hand tied behind our back today than we did then. If we do, our liberal principles will perish alongside our civilisation.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Toby Young is associate editor of The Spectator.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in