‘He never went away. All those other things that we thought were here to stay, they did go away. But he never did.’ Who was Bob Dylan talking about earlier this year? Woody Guthrie? Elvis Presley? Or maybe, halfway through the sixth decade of his own career, himself? But no. The man in question was Frank Sinatra — the inspiration behind Dylan’s latest album, Shadows in the Night.

That record is a collection of covers —from the great American songbook — ‘Autumn Leaves’, ‘The Night We Called it a Day’, ‘What’ll I Do’. We call such songs standards, as if they have been set, if not in stone, then at least on the stave, forever. But that isn’t so. The fact is that when these songs were first performed, 70, 80, 90 years ago, they didn’t sound anything like the moody tone poems right now echoing around your head. They sounded like light opera: all barrel-chested bombast and hammy vibrato trills. The moody tone poems were pretty much invented by Sinatra — the man who standardised the standards. Nobody, not even Dylan, who has no real singing voice and who often enough bends his own numbers out of all recognition, can cover a Sinatra song without sounding something like Sinatra.

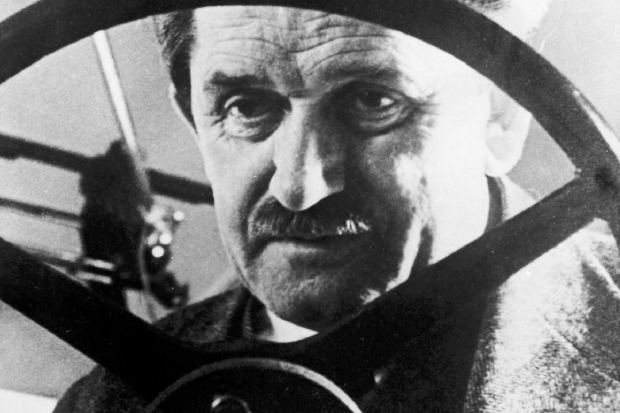

Sinatra sounded like Sinatra because he did more than just hit the right notes in the right order. (Sometimes he didn’t even do that. Richard Rodgers and Cole Porter were forever imploring him to please sing their songs as they’d written them.) He sounded like Sinatra because he made decades-old songs sound as though they were being written in blood as he sang them. Long before rock ’n’ roll critics had invented their cult of artistic authenticity, Sinatra had turned the 32-bar song into a fully expressive form. He sang those songs as if they meant something to him.

A lot of the time they did. Sinatra really had yearned and burned for someone ‘Night and Day’; he really had stayed up ‘In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning’ moping over ‘The Gal that Got Away’. Not that he understood women. The three moods his work conjures — goggle-eyed desire, foot-stomping passion, lachrymose despair — are all essentially adolescent. They bespeak a man who knew as much about women as Freud did. Maybe Sinatra’s second wife, Ava Gardner, was right when she remarked of his third, Mia Farrow, that ‘Frank always wanted a fag with a pussy’.

‘It was Ava who taught Frank how to sing a torch song,’ Sinatra’s most favoured arranger/conductor Nelson Riddle once said. ‘She was the greatest love of his life, and he lost her.’ Their crazed romance is the subject of John Brady’s Frank and Ava: In Love and War, one of a clutch of books being published to mark Sinatra’s centenary. It is a sordid, soul-destroying read, and not just because of Brady’s execrable prose. Tantrums, rows, punches, pistols — the Sinatra/Gardner marriage was a tabloid inferno from the get-go. The best that can be said of it is that in making the lives of its two halves so miserable it brought a little comedy into everyone else’s.

And tragedy. It’s possible that had Sinatra never fallen for Gardner we would still have albums like Where Are You? and Only the Lonely. But they would surely have felt more of a put-on, have lacked the harrowing clarity and acrid yearning of the records we do have. For Gardner didn’t only break Sinatra’s heart. She broke his voice too. Before her he had been an almost heroic tenor. After her he was a hectored baritone. Yet the slide down the musical scale only made him ring more true. As Elvis Costello remarks in a mordant essay in the otherwise picture-dominated, limited-edition Sinatra (edited by Amanda Erlinger and Robert Morgan), Sinatra post-Gardner often enough spoke ‘the lowest part of each melody … [giving] him a great sense of tragedy and intimacy — people began to feel he was singing just for them’.

The far less costly Sinatra 100 is a visual treat too — page after page of pictures in which, in one glorious get-up after another, Sinatra proves Dean Martin’s contention that ‘It’s Frank’s world. We just live in it.’ Well, it was until the mid-1960s anyway. Then, as James Kaplan points out in Sinatra: The Chairman (the second volume of a monumental two-part biography that, if not the last word on its subject, certainly puts paid to J. Randy Taraborelli’s tittle-tattling Sinatra: Behind the Legend and the cackhanded boilerplate of Spencer Leigh’s Frank Sinatra: An Extraordinary Life), Sinatra suddenly began to fill out. Overnight the formerly flute-thin crooner became just another midlife sad sack.

At the same time, as the ever-aggrandising Kaplan fails to add, Sinatra’s work went into decline. Pop and rock, which only a few years earlier he had decried as ‘phoney and false’, were now so dominant that even he couldn’t steer clear. The results weren’t pretty, and it would have been best if Sinatra had retired. Or at least stayed retired. As it was, he spent most of the 1970s making comeback gigs under come-off-it wigs. A few years later things got worse, thanks to the release of not one but two collections of overdubbed duets — with the likes of Bono and Julio Iglesias — albums that might have been recorded in order to define the phoney and false. Sinatra’s standards were slipping.

But his standards weren’t. For 15 years or so from the early 1950s on, he never put a foot wrong in the studio or on stage. Offstage, of course, things were different. Probably we’ll never know what really went on between Sinatra and the Mob. (Not even Kaplan, whose two volumes run to more than 1,600 pages of closely printed text, has the dope on that deal.) The likelihood is that just as Sinatra was babyish about beautiful women, so he was infantile around violent men. Then again, so are many of the rest of us. The difference is that we can’t sing ‘I’m a Fool to Want You’ and make it sound like the end of the world. ‘Nobody,’ Dylan said in that interview, ‘touches him.’ Thankfully, we have him to touch us.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Frank and Ava: In Love and War by John Brady (St Martin’s Press, $26.99, pp. 304, ISBN: 9781250070913)

Sinatra edited by Amanda Erlinger and Robert Morgan (ACC Editions, £1,000, pp. 400, ISBN 9781851498031)

Sinatra 100 by Charles Pignone (Thames & Hudson, £40, pp. 288, ISBN 9780500517826)

Sinatra: The Chairman by James Kaplan (Sphere, £30, pp. 980, ISBN 978187445285)

Sinatra: Behind the Legend by J. Randy Taraborelli (Sidgwick, £20, pp. 588, ISBN 9780283072062)

Frank Sinatra: An Extraordinary Life by Spencer Leigh (McNidder & Grace, £15, pp. 350, ISBN 9780857160867)

. Christopher Bray has written biographies of Michael Caine and Sean Connery.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in